Our previous posts describing First Vespers and Compline of the Feast of the Circumcision at the Cathedral of Sens, as codified by the Lord Archbishop Peter of Corbeil, have, we hope, helped our readers picture the centrality of liturgical celebration in mediæval communities. Long offices were no burden; to the contrary, they were much loved. After all, in the Age of Faith the church was “the common refuge of all, where all of social life resorted. A man prayed there, the town council met there, and the clock was the voice of the city.” Let us recall that

As impressive as Catholic ceremonies remain, they have lost much of their former magnificence. The influence of the Reformation in the 16th century, which gave rise to a religion reduced to its most simple expression, contributed to the impoverishment of the Catholic religion that strove against it, even while permitting an aesthetic element that addressed the soul by way of the senses. In the Middle Ages, everyone believed humbly. Everyone understood and loved the religious ceremonies, which were never too long or too magnificent for their taste. […] Feast days, which were much more numerous than today, were for the poor souls of this world… days of rest whose coming they welcomed with enthusiasm…What a joy to visit the neighboring abbey for a whole day of leisure, to contemplate the splendors of a worship that was at once prayer, teaching, and spectacle! How earnestly they wished these feasts to be many, and the offices to be long![1]

Mattins

The canons bestirred themselves right early the next morning in eager anticipation for the day’s liturgical festivities. The Night Office began as usual with the words Domine, labia mea aperies, but rather than the usual reciting tone, it is sung to the melody of an antiphon with the same words borrowed from Lauds of the Second Sunday of Lent. Similarly, the next verse, Deus, in adjutorium, is sung to the melody of the beginning of the Introit of the 12th Sunday after Pentecost, which is set to these same words. The Gloria Patri is sung to the Paschal tone of the Invitatory Psalm 94, although transposed from the sixth to the seventh mode to match the preceding.

It is remarkable that each of the three Nocturns begins with a proper Invitatory. Some 18th-century liturgists such as Jean Lebeuf surmised that this was an atavism, recalling the time when each Nocturn was sung separately. There is, however, no indication in this MS. that the Nocturns were separated, and the plethora of Invitatories is more likely meant to add solemnity rather than recall an archaic practice. Each of these Invitatories is followed by a hymn, all of which are actually sequences borrowed from Mass, presumably because the ancient repertoire had no proper hymns for the Feast of the Circumcision itself. As at First Vespers, sequences from Mass are also substituted for the versicles in each Nocturn.

The nine responsories are mostly the same as in the Tridentine breviary, with some variations also found in other French uses.

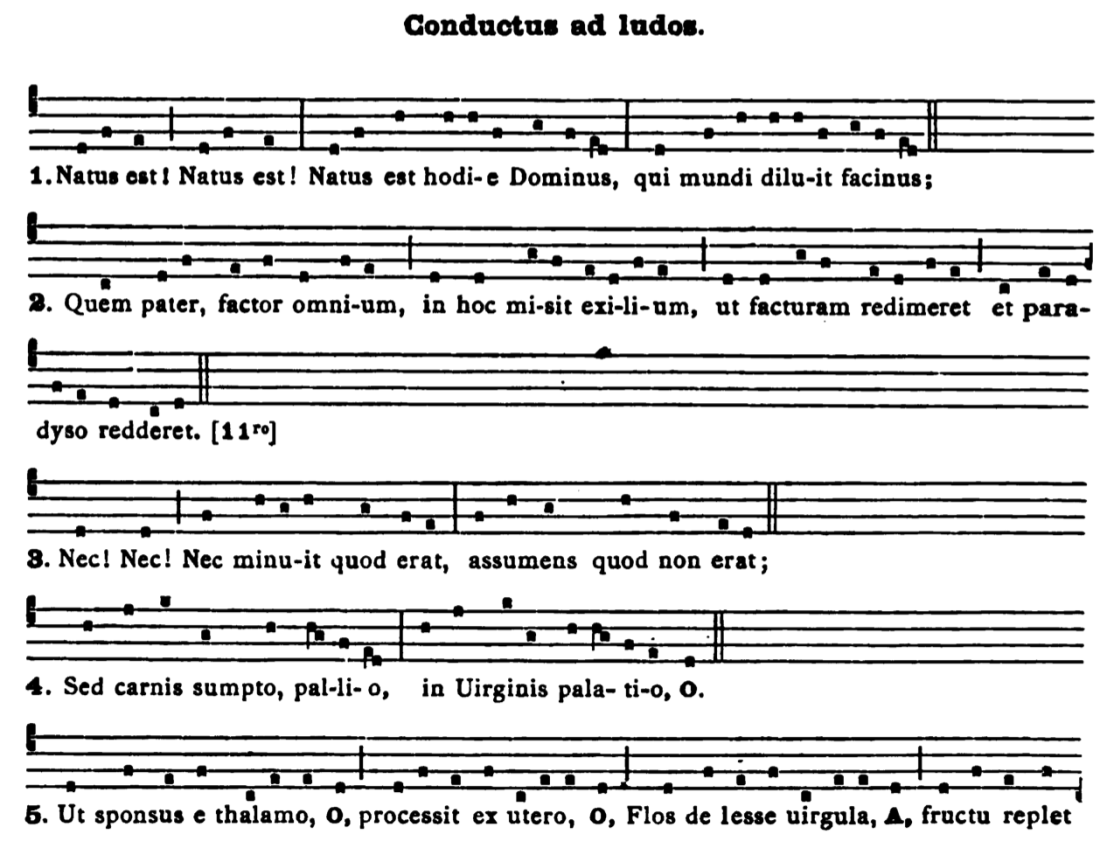

In the MS., a conductus ad ludos follows Mattins. This was a charming Christmas carol sung by the canons as they made their way to the performance of a musical play on a Scriptural subject. No more information exists on what was performed in Sens, but in the Cathedral of Beauvais in the 13th century, the Ludus Danielis was performed after Matins of the Circumcision. The chanting of the Te Deum concluded this liturgical drama.

Lauds and the Little Hours

The rest of the Offices proceeded on similar lines. At Lauds, the antiphons and psalms are as in the Tridentine breviary, but, as in Mattins, the hymn and versicle are replaced by sequences. A jolly Benedicamus Domino hymn finishes off the hour.

Prime begins with the Deus, in adjutorium set to the melody of the same Introit as at Mattins, but from Domine, ad adjuvandum, a recitation tone takes over, curiously on the first mode transposed, even though the Introit melody is of the seventh mode; the result is not too felicitous. The Alleluia is a short melisma.

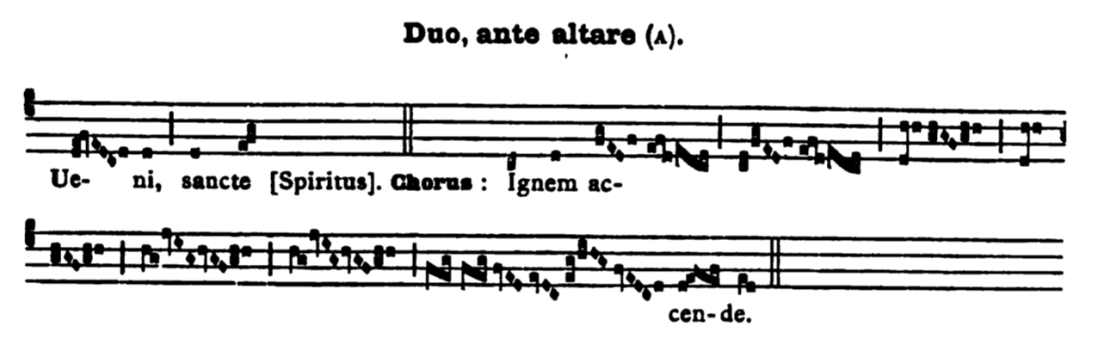

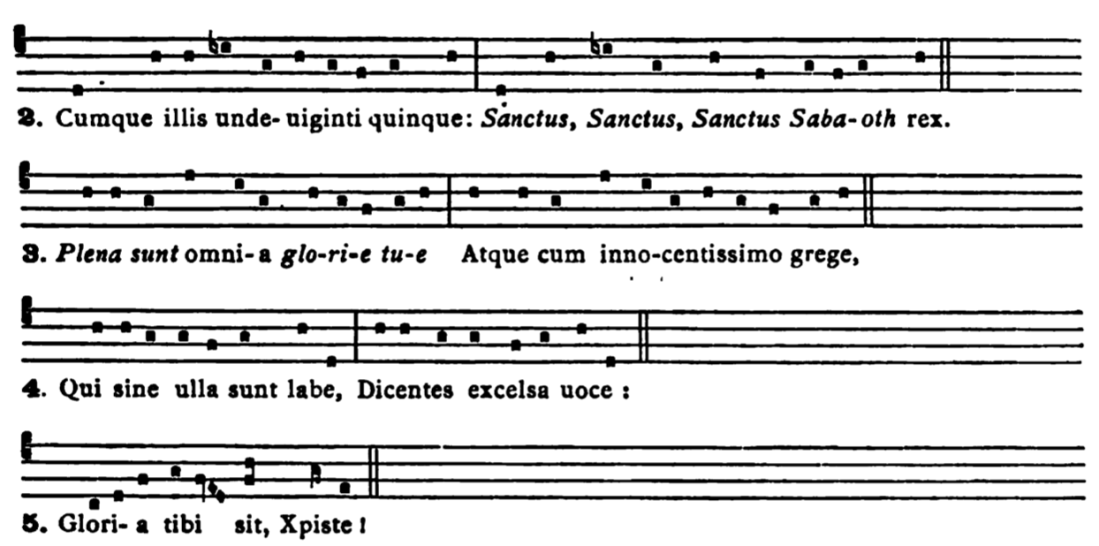

Then two clerics standing in front of the altar intone the epicletic sequence Veni, sancte Spiritus, at the words Ignem accende the choir joins in with a spectacular melisma interspersed into the sequence’s original melody. This melogenic trope was otherwise used at Sens to enhance responsories on solemnities. Only after this sequence is the usual hymn of Prime sung, troped with the exultatory words Fulget dies! Fulget dies ista!

As at Compline, the words of the usual versicle for Prime are used as the basis for a short hymn, and the same festive preces—farced Kyrie, farced Pater, farced Apostles’ Creed —follow. The canons held their chapter office after Prime as usual.

Terce, Sext, and None all feature a short sequence replacing the usual versicle and a Benedicamus hymn at the end. They are otherwise as in the Tridentine breviary.

See the other posts in this series:

1. A Feast of Fools?: First Vespers

2. Compline

4. Mass and Second Vespers

5. Why the Office of Peter of Corbeil was Suppressed

6. A New Years’ Apéritif with the Canons of Sens

NOTE:

[1] Marius Sepet, Le drame chrétien au moyen age, Paris, Didier, 1878, p. 21 et seq.