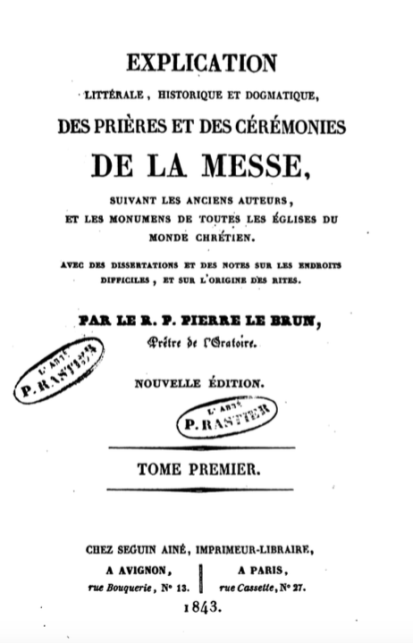

PREFACE

The Excellence of Sacrifice

There is nothing greater in all religion than the Sacrifice of the Mass. The other Sacraments,[1] nearly all the offices, and all the ceremonies of the Church are but means or preparations for its celebration, or for worthy participation in it. In it Jesus Christ offers himself for us to his Father. In it he renews each day, as the Eternal Priest, the oblation he made once on the cross, and in it he gives himself to be eaten by the faithful, who thus find at the altar the consummation of the spiritual life, since in it they feed upon God himself.

We may say that the Sacrifice of the Mass transforms our churches into heaven. There the Divine Lamb is immolated and adored, as St. John describes[2] him to us in the midst of the heavenly sanctuary. The spirits of the Blessed, aware of that which is worked upon our altars, come and assist there with fear and trembling that inspire the highest respect. St. Chrysostom, along with other ancient Fathers, has taught this based on deeds of the highest authority,[3] and this truth of the presence of the Angels has always been so well known that St. Gregory the Great had no difficulty in saying:[4] “What faithful soul can doubt that at the voice of the priest, and at the very hour of the immolation the heavens are opened, the choirs of angels come to assist at the Mystery of Jesus Christ, and all creatures celestial and terrestrial, visible and invisible, are all united in this one moment?”

In our churches we indeed do nothing less than what the Saints do without ceasing in heaven. There, we adore the holy Victim immolated by the hands of priests, and all the Saints adore this same Victim in heaven, the Lamb without blemish, represented standing but slain,[5] to show his immolation and his glorious life. All the prayers and all the merits of the Saints rise as a sweet perfume before the throne of God: as St. John expresses[6] by the thurible that an angel holds in his hand, and by the altar whence the prayers of the Saints rise before God’s face. The Church on earth also offers incense to God on the altar, as a sign of the adoration and prayers of all the Saints who are here below or in glory. All adore him with one heart in heaven and on the earth, for we have on our altar here below he who sits on the heavenly throne.

Origin of the prayers and ceremonies that accompany the Sacrifice

What is essential in the prayers and in the ceremonies of the Mass comes to us from Jesus Christ. The Apostles and the apostolic age added what was fitting during the times of the persecutions by the Jews and Gentiles, for it would have been dangerous for ours to have had any resemblance to them. The Rite was not fixed: it would not take a new exterior shape until the Christian religion became that of the Emperors and the most glorious in all the earth, and there was no more fear of the impression that the rites of Judaism or paganism would make on the new Christians. Until that time there were very few usages or ceremonies, but they were observed as law as St. Paul had recommended.[7] Saint Justin, writing a short time after the Apostles,[8] gives us to understand[9] that there were prayers that were more or less long according to the devotion of the priest or the time available, telling us that the one who offered the sacred gifts prayed as much as he could; and St. Cyprian teaches us that there were certain fixed elements that could not be omitted or altered. For what other sense can there be to what he said against a schismatic who withdrew from the unity of the bishops, who dared to raise up another altar and make another prayer using illicit words; precem alteram illicitis vocibus facere?[10]

After peace was established in the Church at the beginning of the fourth century, and magnificent churches were consecrated where the divine service could be carried out with more solemnity, the number of prayers and ceremonies grew. Some were ordained by St. Basil and St. Chrysostom, who gave their names to the two liturgies used by the Greeks to this day: and it is for the same reason that the liturgy of Milan was named the Liturgy of St. Ambrose. In the rest of the West a great number of learned men applied themselves to composing Orations and Prefaces that were examined by the Councils: those of Carthage[11] and Milevis[12] in the time of St. Augustine ordered that they should not be said at Mass because they had not been approved by the bishops of the province. Thence came the great number of prayers that fill our Missals.

Origin of the variety of prayers and ceremonies

Around the same time, Pope Innocent I was surprised to discover the variety among the Latin churches who had received the Faith from St. Peter or his successors. He desired that all churches be conformed to Rome. But it was difficult to reduce to perfect uniformity that which had been left to the zeal and inspirations of a great number of saints and learned bishops. Voconius, bishop of Africa, composed a collection of orations that we call a Sacramentary; and Museus, a priest of Marseilles, toward the middle of the 5th century, was praised for his talent in composing similar prayers that were used in many dioceses. Saint Pope Gelasius, at the end of the same century, also created a Sacramentary to which Gregory the Great, one hundred years later, made some changes. From that time until the Council of Trent, the Roman Missal was called the Missal of St. Gregory. Pepin, Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Charles the Bald introduced it into the churches of France and Germany. It was introduced in Spain in the 11th century. All these churches did not, however, renounce their own usages entirely: for from the year 938 Pope Leo VII, writing to the bishops of France and Germany, criticises the variety of their offices.[13] But it was not difficult for these bishops in their defence to rely on the authority of St. Gregory who had led the abbot Augustine[14], after sending him to England, to take from the churches of France anything good he might find in the divine offices. From the complaint of Leo VII and Gregory VII in the 11th century, we learn from there was variety even among the offices at Rome itself.[15]

Whatever reason there could be to desire an entire uniformity, we have found it advantageous to rediscover ancient usages and even to receive new ones, and by the salutary commerce that has always taken place between the churches, they have communicated that of their own which is good and profitable to the others. Rome herself has often followed the other churches who had received almost everything from her. It is thus that, after having ordered the suppression of the ancient Gallican Rite and the Gothic [Mozarabic] Rite of Spain, she saw fit, as we shall see, to take prayers and ceremonies from them and insert them in the Ordinary of the Mass, which since the 13th century has been what it is today, and merits the praises that all the Catholic Churches make of it.

(to be continued…)

**For a PDF of the French original, see here.

Comments or criticisms of this translation are welcome.

[1] ST III, q. 73, a. 3: “Per sanctificationes omnium Sacramentorum fit praeparatio ad suscipiendam Eucharistiam.”

[2] Apoc. 7:17.

[3] Chrys. De Sacerd. I. 6. c. 4 homil. de incompreh. Dei nat.

[4] Quis enim fidelium habere dubium possit, in ipsa immolationis hora, ad Sacerdotis vocem coelos aperiri, in illo Jesu Christi mysterio Angelorum Choros adesse, summis ima sociari, terrena coelestibus jungi, unumque ex visibilibus atque invisibilibus fieri ( S. Greg. Dial. l. 4. c. 58).

[5] Agnum stantem quasi occisum (Apoc. 5:6).

[6] Data sunt illi incensa multa, ut daret de orationibus Sanctorum omnium super altare aureum, quod est ante thronum Dei, et ascendit fumus incensorum de manu Angeli coram Deo (Apoc. 7:3, 4).

[7] Omnia… secundum ordinem fiant (1 Cor. 14:40).

[8] 140 A. D.

[9] Apolog. 2.

[10] Cypr. de unit. Eccles. p. 83.

[11] Conc. Carthag. III. cap. 23.

[12] Conc. Milev. III. can. 12

[13] Conc. tom. 9.

[14] Lib. 12 ep. 31.

[15] Can. in die de Consecr. dist. 5.

As a Frenchman, I would very much like to see the original ^^

LikeLike

I would like to be able to insert a good plain text version of the French, but unfortunately I have been unable to find one. The wiki source material is largely uncorrected

(https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Lebrun_-_Explication_litt%C3%A9rale_historique_et_dogmatique_des_pri%C3%A8res_et_des_c%C3%A9r%C3%A9monies_de_la_messe_-_Tome_1_(1843).djvu/14)

Until then, I hope a small PDF file of each section will be of use to you: it has been added below the text.

LikeLike