INTRODUCTION

PREFACE to Volume 1

Here De Vert shows that the frequent changes, variations, and dispensations of Church practices show that the Church does not hold mystical or symbolic reasons for the ceremonies as primary. Note especially his paragraphs on Baptism**.

PREFACE

Volume 2

In the preface of the first part of this work, I showed that this method of explaining the ceremonies of the Church according to their simple, natural and historic sense was nothing new, and that I have taken as my model a great number of authors renowned for their knowledge and piety.[1]

But this was insufficient. It still remains to show that the Church herself lends me this idea, and that my own mind differs in nothing from hers. God forbid I should ever think otherwise, or depart from her spirit and views in anything, even in trivial matters and points of less importance.

Nothing seems easier than to justify this proposition, and to show how at every step of the way and with all her conduct the Church approves as true, proper, and original meanings of her ceremonies those that I call simple, natural, and literal. If it were otherwise, and if she saw her ceremonies as founded solely upon spiritual reasons, and instituted for purely symbolic and mystical reasons, then because these sorts of reasons are not susceptible to change and because mystical realities are fixed and constant, once room is given to figure and allegory the ceremony must remain unaltered forever. It would follow that the Church herself was immovable–even in her customs and regulations. Her ordinances and laws, rites and ceremonies–once we supposed them to be founded upon such mystical reasons, as upon stable and permanent foundations–would thereby become essential and indispensable with no room for exception. In no circumstance would it be permitted to the Church to innovate or change anything in her whole exterior conduct. This would in no way accord with her discipline, which is variable and changing according to circumstances of time, persons, and place.

[Impediment to Orders for the Twice-Married]

If it had always been true, for example, that those who have married more than once were excluded from Holy Orders merely because they had divided their flesh (as the mystical authors would say), and having shared it (so to speak) with others, they are no longer able to represent the union of JESUS CHRIST with his Church[2] which is one, and their marriage cannot be the image of the perfect love of this virgin Spouse for her virgin Groom,[3] this resulting defect of the sacrament constituting an irregularity; if, I say, it had always been true that this was the spirit and essential, primitive motive, principle cause and fundamental original reason that St. Paul prohibited a man who had more than one woman from the sacred ministry, then must also wonder why it is so easy, as it is, to lift this prohibition, founded as we have supposed on such sublime and serious, mysterious and thus respectable reasons. But if the apostle made this rule to accommodate the morals of his time and especially in order not to be less sensitive than the Jews and pagans, who also forbade from ministry at the altar those who had had more than one woman,[4] then we would easily judge that there are cases where this reason which is nothing more than mere convenience and pure convention, should give way to other considerations that justify dispensing this canonical impediment.

[Impediment to Marriage within a Certain Degree, Marrying in Penitential Seasons]

The same holds for some other customs that have come to us from the Jews and pagans, in which the Church has no trouble giving dispensations if she does not find just and legitimate reasons for them. Certainly she would be loth to do so if she thought that everything was mystical in the institution of all her practices. Thus in the case of the prohibition of marrying between parents of a certain degree (a prohibition that seems to have come to Christians through the Jews and Romans), indulgence is given very frequently. [5] This is true for innumerable other constitutions and ordinances, in which she gives dispensation so easily only because she regards them as being founded on opinions and motives that are subject to change and variation; such is the case for most of her practices and customs. Accordingly dispensation is nearly always granted for marrying in Lent and Advent (in this case we might even say the exception has become the rule), because we know that the Church’s prohibition on celebrating nuptials during those times is only the consequence of the ancient practice of continence on fasting days; since in our time such continence has become a matter of simple counsel, superiors have more leeway to relax the discipline on this point. Moreover, I have heard that in some diocese one is no longer even required to give a reason to obtain this dispensation, so well informed they are on the true reason and spirit of the law.

[Interval between reception of major orders]

In the same way, the Church finds it very easy to dispense with the usual interval of time between the reception of two orders, because there is reason to believe that the reason for the introduction of the span of one year between the reception of orders is that in ancient times ordinations were done only once a year in Rome, in the month of December, in accordance with the words repeated so often in the Lives of the first popes, fecit ordinationes mense decembri.[6] Consequently since orders were received only once a year it was necessary to wait an entire year before being promoted to the next order. But since at present orders can be conferred regularly on every Ember week, and even more often if desired, namely on the Saturday before Passion Sunday and Easter Saturday, several bishops have deemed that this span of three months can suffice for an interval between orders. […] Nothing is more frequent than these extra tempora, i.e. dispensations to be ordained outside of Ember days. And whence comes this facility of obtaining dispensations, if not because, in light of the fact that ordinations were done every Sunday in some centuries […] it seems less difficult to return to this use and that we may without scruple give an exception and condescension, even for cases without grave reasons? Thus it seems that what most facilitates the obtaining of these dispensations is nothing other than the recognition that there are reasons that form the basis of this regulations, and that these reasons were simple, indifferent, and variable. If on the contrary there were mysteries and spiritual senses hidden under these rules, these superiors would behave entirely differently and would be careful not to dispense anyone from them.

Now for practices of a different nature. If it were true, for example, that the clerical tonsure, at its origin and institution, had been nothing else than the image and symbol of the crown of thorns placed on Our Lord’s head, would we not be obliged by necessity to hold to this idea and practice, or would it be permitted in any case or for any reason to alter such a mysterious and significant sign as this? and would not the Church herself, on the contrary, have to require clerics in all times and from the very beginning, to wear a tonsure as similar as possible in form to the one worn by Our Lord, without permitting it to be enlarged or diminished at will? But the fact that the Church permits these ministers to have different tonsures, some more large or straight than others, us a visible sign that she does not at all regard the crown of Our Lord as the model and measure of what all clerics must wear. She gives another origin to this practice. Thus, she knows she has the freedom to regulate the form of the tonsure as she judges best, in accordance with circumstances of time and place.

Again, if it were true that infants are named at their baptism only in order to put them under the special protection of the Saint whose name they take, would the Church leave the choice up to the will of every individual to change this name at confirmation, clothing, or religious profession?

[Altar Decorations and Vestments]

Could we easily believe that the bishops would permit so many churches to have no antependium (parement) in front of the altar, if they were not informed that this antependium’s only purpose originally was to protect the relics that were placed under the altar; so that, in relation to this original use, the antependium has become entirely useless in churches where relics are no longer placed under the altar?

Is it conceivable that they would set their hands so readily to the destruction of the jubés, if they did not see that, since these types of tribunes were only erected to such a height so as to ensure that the reader’s voice would carry and be heard by the whole assembly, and that suffices to attain this purpose if the lector stands only a few feet above the others; and that there is no need to build these jubés in the form of galleries and to raise these huge masses of stone that can still be seen, especially in the cathedrals and collegiate churches, and that entirely block the faithful’s view of the choir and sanctuary?[7]

The same obtains for the practice of suspending the Blessed Sacrament above the altar. Would the re-establishment of this practice in many places be permitted, to the prejudice of tabernacles, unless we knew that this was the ancient custom (especially since the 6th century[8]), and that tabernacles have only been in use for about a hundred years?[9]

Finally, it is the same for certain sacred vestments that would never be allowed to be cut, and which have been cut to the point we see today, if we had not learned from many renowned authors[10] that these vestments originally were not peculiar to the ministers at the altar, so that taking account of their original use, it doesn’t seem that there is anything amiss about letting them gradually take on a different form, more convenient and comfortable. Especially with regard to the chasuble, which formerly used to cover the priest entirely all around, if it were certain that it had this form for the sole purpose of being the symbol of charity that covers (in the words of St. Peter) a multitude of sins, would it have been, so to speak, relaxed to the secular arm, namely, left to chasuble-makers to cut them, shorten them, scallop them, and reform them to the point that they no longer cover the arms or legs? Truly, would it have been permitted to thus disfigure a sacred vestment consecrated by the moral idea that had been attached to it from the beginning?

Perhaps if people reflected well on all these consequences, they would be more hesitant to suppose that the Church has ideas and intentions that it is very doubtful and very uncertain that she has ever had. No priest and no bishop thinks any longer that the stole and maniple were destined since their institution to represent the bonds with which our Lord was tied when he was taken before Pilate.

If they imagined these vestments from this symbolic point of view, would they allow them to be so largely disguised by the ornaments embroidered onto them, so that today they have no resemblance to the cords with which the Savior of the world was tied and bound? If any bishop still believed that the action of kissing the altar at Mass contained any mysterious meaning, would he believe that it is sufficient to kiss only the wooden border that surrounds the altar? For, if we suppose that the altar was a figure of Jesus Christ, as certain mystical authors claim, could this symbol and image be applied to a simple wooden rail on which the antependium is set?

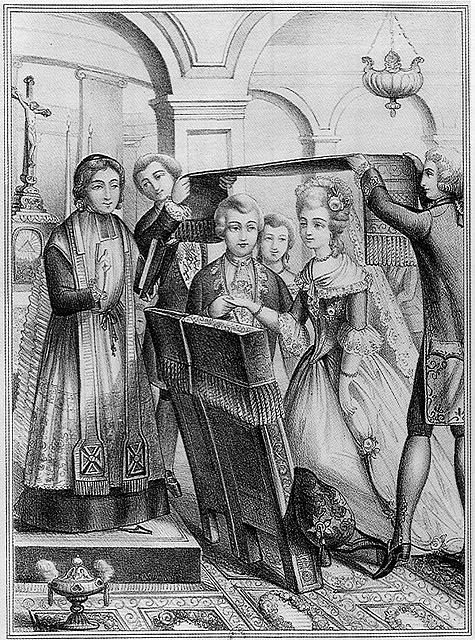

*[Baptism]*

But how should we explain the fact that Pope Innocent II decided that there was no obligation for women to be churched after childbirth, if not because (without looking about for anything mystical in the ceremony), this great jurist and theologian saw that this practice belonged to a law that had been abolished by the Author of grace and truth, and so allowed the Church to use this blessing as a laudable pious custom, a custom of counsel and devotion and not a duty of precept? Moreover, how was it permitted that the full immersion of the whole body in the ceremony of baptism was changed to a simple pouring or infusion of one part of the body? It is because we know that this practice of plunging was originally a form of washing infants at the moment of their birth for reasons of physical health. Thus it can never be part of the essence of a sacrament, where the point is not to wash away physical uncleanness, and so the amount of water used does not matter, and as long as the sacrament is administered with water, then infusion, aspersion, or immersion or all equally good, and all forms are judged valid.[11] But if, on the contrary, the Church regarded immersion as essentially instituted to be an express representation of the fact that, being baptized into the death of Jesus Christ, we are also mystically buried with him, she would have taken great care to prevent this practice from changing, knowing well that whatever is the ground and substance of the sacraments is unalterable and indispensable. From this alteration of the discipline with regard to baptism we can see that the Church regards baptism by immersion as a simple custom that has come down to her from the tradition of the Jews or pagans, or perhaps from both together, and from all the nations of the world.[12] The same applies to the unction that precedes and follows the baptism. Understanding the physical, sensible causes for the institution of this practice, the Church has found it appropriate for good reasons to reduce it to only certain parts of the body, where formerly it was done on the whole body. On the other hand, if she had believed that this ceremony had been introduced only to give the catechumen power against the temptations and attacks of the devil, or to indicate that the neophyte takes part in a spiritual unction (reasons all used later on for the instruction and edification of the faithful), she would never have allowed it to be touched or reduced in any way, because that would have weakened the mystery, rendered its signification defective, and thus diminished the effects of the holy chrism and oil of catechumens.

[[NB footnote 12: “Though this did not keep the apostle Paul […] from finding excellent relations and wonderful allusions between this manner of plunging entirely into the water and the faithful’s being buried with Jesus Christ and rising from the water as Jesus Christ rose from the tomb. But it is one thing to make allusions and applications, metaphors and comparisons, and quite another to say that the original purpose for the institution of this action was to represent and signify the burial of the faithful with Jesus Christ. I mean to say that all these spiritual and symbolic viewpoints are not the cause and principle of the immersion, and played no part in the intention of those who instituted it. Rather, the fact of immersion merely provided the occasion for all these ideas and reflections.”]]

[Mystical Reasons Lead to Contradictions]

Another thing that seems to demonstrate that the Church is very far from envisaging these sorts of reasons as the only reasons for the establishment of her ceremonies is the fact that if this was the case, she would often fall into contradiction in her practice. For instance, on the one hand the Church gives us to understand that the candles on our altars burn for no other reason than to express Jesus Christ who said that he was the light of the world; and at the same time they are not lit at Prime, Terce, Sext, or None, when Christ is no less the light of the world than at Matins, Lauds, and Vespers, when they are lit. This would not be coherent and the Church would be contradicting herself. Assuming this symbolic reason were true, we would have to leave the candles burning continually, and not only at certain divine offices, because, as the Apostle says, “(Heb. 13)” He is “the true light of man, who enlightens the world” (John 1) at all times of the day as well as during the hours of night. He is eternally the splendor of the “glory of his father,” (Heb 1:3; Sap. 7:26).

If we ask the Church for the reason why she lights candles at certain hours of the office and not at others, she responds very simply and naturally, it is that there is no need for superfluous light during the day when Prime, Terce, Sext, and None are said, but only at night and dawn when Matins, Lauds, and Vespers are sung.

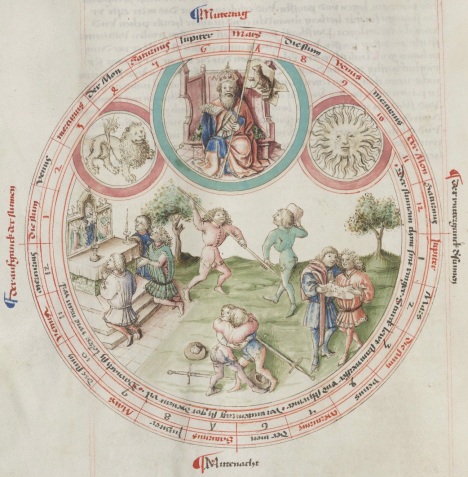

Are there many communities and famous corporations who are persuaded that the primitive reason for the institution of the hours of the office is precisely to honor and celebrate the various mysteries of Christ’s life? such as for example the birth of Our Savior at Matins, his resurrection at Lauds, the morning of his Passion at Prime, the descent of the Holy Spirit at Terce, the crucifixion at Sext, his death at None, his burial at Vespers, his lying in the tomb at Compline?

If it were true that in instituting the Divine Office, the Church had intended to honor in each of these hours the mysteries that took place during them–how Our Lord came into the world at night, how he rose at dawn, valde mane, how the Holy Spirit descended around Terce, cum sit hora diei tertia, how Our Lord was crucified around the hour of Sext, erat hora quasi sexta, that he died around None, circa horam nonam, and that he was buried in the evening–then it would never be permitted at all to change the order of the offices and thus obliterate all these intentions of the Church.

But an evident proof that all these congregations do not believe that the Hours were instituted for these sorts of sublime and mysterious reasons, is the freedom that they give to anticipate or postpone the Hours, to distribute them according to convenience or the will of their superiors. Thus, at Paris for example, they say Matins followed by Lauds at anytime during the night, between five o’clock in the evening of the previous day and six in the morning of the next day. Likewise they say Prime sometime between five thirty and eight in the morning; Terce between eight and ten; Sext between ten and eleven forty-five; None between mid-day and three; Vespers between one and six; and Compline between three or four and nine. Nothing could show more clearly how these hours are arbitrary, and how far the Church is from thinking that the primitive reason, the reason for the institution of these Hours was to honor the various mysteries.

Furthermore, would the whole Church have taken it upon herself in Lent to anticipate Vespers at noon and celebrate at that hour a mystery that happened in the evening? It is thus much more natural to believe that all these particular churches and the universal Church herself regard the determination of the Hours of the Office as a tradition coming from the Jews, who actually assembled for prayer at about the same hours as Christians; namely in the morning[13], at 6,[14] and 9,[15] and in the evening,[16] not to mention the night prayers.[17] Therefore the Churches can easily anticipate or postpone these Hours because in the final analysis, just as the jews had their reasons for choosing these hours, the Churches about which we are speaking also believe that they have sufficient reasons to change the times of the hours and choose other times.

Therefore, we have found proof of my thesis everywhere: that the ease of obtaining dispensations and the variability of the Church’s discipline, especially with regard to the rites and ceremonies, comes from the fact that this discipline is founded on simple reasons that are nearly all based either on the customs of the ancients, or on the relation between actions and words or between words and actions, or on necessity, or on propriety and convenience.[18] All such practices and reasons are subject to change, because what is convenient at one time is not at another. As soon as these reasons no longer hold, it would seem permissible at the same time to abolish the practices connected with them. If, on the other hand, all these practices were meant to figure and represent some mystery, then the respect superiors had for these reasons would prohibit them from permitting the changes that are introduced nearly every day in the ceremonies and exterior cult of our religion.

[….]

It was the changes introduced into the ceremonies that caused people to forget and lose sight of the sensible and natural reasons of their establishment. If people only wore their hair short and their clothes long once again, as they did less than 200 years ago, they would very quickly see the reason for the tonsure and the religious habit and the whole exterior vesture of ecclesiastics.[19] If they could see the chasuble in its ancient form, they would quickly see why it is lifted at the elevation of the host and chalice. If the maniple became a handkerchief once again, they would see what the manipulus fletus mentioned in the vesting prayer is. If on Holy Thursday all priests celebrated Mass together with the bishop in the cathedral churches, with the parish priest in the parishes, or with the superior in the monasteries, and therefore with the priests vested in their priestly habits, they would know why they take communion on that day with the stole.[20] If Tenebrae is restored to midnight, so that the office began in darkness and ended around dawn, they would see that the Church was not mistaken at first to light a great number of candles during this office and extinguish them gradually as the day approached, and to extinguish them all at the end of Lauds when day had broken. If on Sunday before Mass, we began once more to bless and sprinkle the holy water, inside and outside the Church, the cemetery, and the common places in the monasteries and cathedral chapters where the canons once lived in common, we would understand the origin and reason for the Sunday procession and why in monasteries and other churches the procession visits the four sides of the cloister. There is no other way to explain this procession or discover its object. [….]

[The Literal Sense and Church Reform]

Understanding the literal and historical reasons is useful for another reason: it allows bishops more easily to remove ceremonies that, through the change of manners and church discipline, no longer seem appropriate. Thus, for example, the archbishop of Sens thought it best to suppress most of the baptismal exorcisms in his new ritual, because it seemed to him that the repetition of these exorcisms, which were once performed on different days, no longer had a purpose after they were joined into one ceremony.

[On Burial Practices]

So there you have it, material already too much for one preface. If I were to give it the full extent of treatment it deserves, there would be enough to compose a book; indeed all the more so because the truth of the system I have proposed has already been sufficiently proved by many judicious and learned persons. It is also useless to speak again about the necessity of studying the simple, literal, and historical reasons for the ceremonies if one wants to understand what is happening at every moment in the Church, either at Mass or in the Office, or during the administration of a sacrament, or any other function. Above all, nothing is more shameful and scandalous than to see pastors and priests who are ignorant of what their ministry obliges them to know and teach to others. A learned bishop of the 16th century, complaining to a cardinal about the ignorance that reigned among most clergy of his day about church ceremonies, said:

“Since our understanding and right intention is the foundation of the sacred worship, whoever is ignorant of what he is doing performs sacred worship in vain, for he lacks the basis, namely the right understanding and intention. How many clergy put on their vestments entirely ignorant of why there are so many and various: priests who have celebrated mass for years, and bishops who have consecrated for years? If you ask them why they do these things, they are speechless and have nothing to respond.”[21]

NOTES:

[1] Among them we cannot fail to mention Dom Edmond Martenne, a scholar of the Congregation of St. Maur, who in the preface to his first volume on the ancient rites of the Church, openly declares that he prefers historical reasons to those commonly known as “mystical”: His igitur attente consideratis…post habitis rationibus mysticis, quas apud editos scriptores quique consulere potest, universos ecclesia ritus more historico representarem, etc.

[2] St. Paul takes what Moses says literally about the union between man and wife, using it to explain the union of Jesus Christ and the Church from a mystical point of view, calling it a great mystery and sacrament: Sacramentum hoc magnum est, ego autem dico in Christo et in ecclesia (Ephes. 5:32).

[3] M. Nicole shows in his Instruction on the Sacrament of Order that, far from being St. Paul’s explanation, it was St. Augustine who was the first to invent it, and that before him the reason for the exclusion of the twice-married from orders was the incontinence that was implied in these second marriages.

[4] On the Jews, see Leviticus 21 and for the pagans, Titus Livius, (Decade 1.50.x, and Alex ab Alex. 50.6. To see that second marriage were detestable to the ancients, as showing some kind of incontinence or weakness, we have only to hearken to Dido, the widow of Sicheus, who reproaches herself for the grievous fault of merely thinking of marrying Aeneas (Huic uni forsan potui succumbere culpa, Aeneid 4).

[5] Trans. note: Consanguinity is forbidden by Leviticus 18 and Deuteronomy 20.

[6] Primi apostolici semper in decembrio mense, in quo Nativitas D. N. J. C. celebratur, consecrationes ministrabant usque ad Simplicium…ipse primus sacravit in Februario (Amalarius II.1). The Micrologus says the same thing. See also Dom Mabillon, in his Commentary on the Ordo Romanus, n. 16.

[7] See M. Bocquillot in his Traité historique de la liturgie, pg. 72.

[8] Following these words of the Council of Tours can. 3: Ut corpus Domini in altari, non in armario, sed sub crucis titulo componatur (The Body of Our Lord should not be placed in a tabernacle but on the altar under the cross.). This is what we find still in many churches where the holy ciborium is suspended at the foot of the great crucifix over the altar.

[9] It is thought that the first tabernacle seen in Paris is that of the Capuchins on the Rue Saint-Honoré.

[10] Among others, Fr. Thomassin, the Abbé of Fleury, etc.

[11] See M. de Meaux in his Traite de la communion sous les deux especes.

[12] Though this did not keep the apostle Paul […] from finding excellent relations and wonderful allusions between this manner of plunging entirely into the water and the faithful’s being buried with Jesus Christ and rising from the water as Jesus Christ rose from the tomb. But it is one thing to make allusions and applications, metaphors and comparisons, and quite another to say that the original purpose for the institution of this action was to represent and signify the burial of the faithful with Jesus Christ. I mean to say that all these spiritual and symbolic viewpoints are not the cause and principle of the immersion, and played no part in the intention of those who instituted it. Rather, the fact of immersion merely provided the occasion for all these ideas and reflections.

[13] Sacrificium matutinum.

[14] Ascendit Petrus in superiora ut oraret circa horam sextam (Acts 10:9).

[15] Petrus et Joannes ascendebant in Templum ut orarent ad horam orationis nonam (Acts 3:1).

[16] Sacrificium vespertinum

[17] Media nocte surgebam

[18] See vol. 1, p. 269, note b.

[19] See pg. 431 ff.

[20] See vol. 1, pg. 348 ff.

[21] To Saint-Pierre d’Abbeville, 25 September 1707.