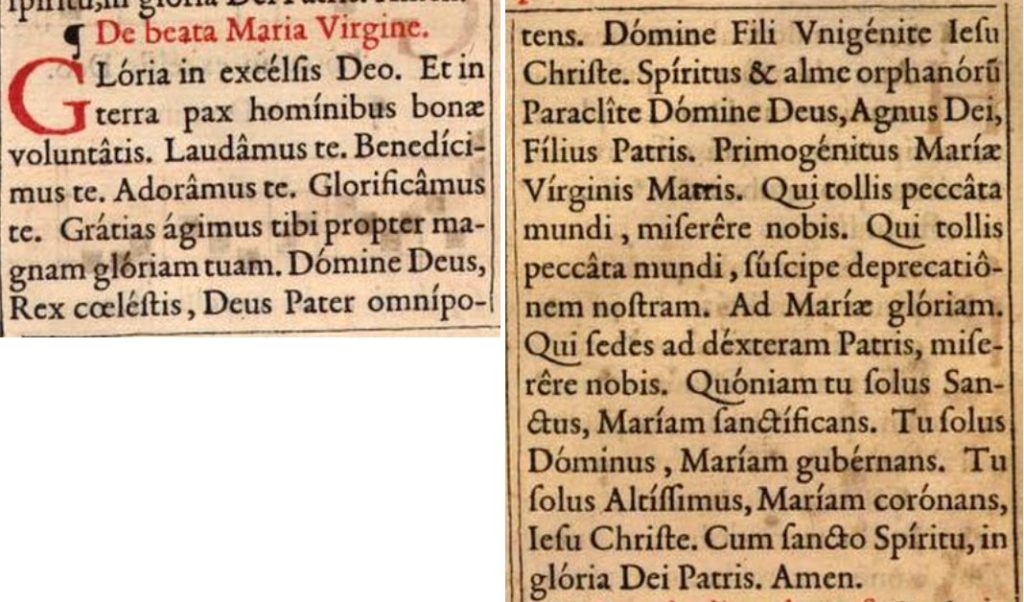

| Gloria in excelsis Deo. Et in terra pax hominibus bonæ voluntatis. Laudamus te. Benedicimus te. Adoramus te. Glorificamus te. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam. Domine Deus, Rex cœlestis, Deus Pater omnipotens. Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe. Spiritus et alme orphanorum Paraclite. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris. Primogenitus Mariæ Virginis matris. Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecatiónem nostram, ad Mariæ gloriam. Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis. Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, Mariam sanctificans. Tu solus Dominus, Mariam gubernans. Tu solus Altissimus, Mariam coronans, Jesu Christe. Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris. Amen. | Glory be to God on high, and on earth peace to men of good will. We praise Thee. We bless Thee. We adore Thee. We glorify Thee. We give Thee thanks for Thy great glory. O Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father almighty. O Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son. O Spirit and kind comforter of orphans. O Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father. First-born of the Virgin Mother Mary. Who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Who takest away the sins of the world, receive our prayer, to the glory of Mary. Who sittest at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us. For Thou only are holy, sanctifying Mary. Thou only art the Lord, ruling Mary. Thou only art most high, crowning Mary, O Jesus Christ. Together with the Holy Ghost in the glory of God the Father. Amen. |

As we mentioned in our introductory post on tropes, these were never explicitly banned by any decision taken by the Council of Trent or appearing in the liturgical books produced in its wake, with one exception: the 1570 Roman Missal includes a rubric insisting that the Gloria in excelsis must always be said as written in the Missal, even in Masses of Our Lady. This was a reaction to one of the most enduringly popular of all liturgical farcings, viz. the Spiritus et alme trope, which adorns the Gloria with sundry acclamations praising the marvels God has wrought in Our Lady.

Our exploration of the rich world of tropes has been heretofore confined to tropes on the Kyrie and, as we have seen, these are almost always melogene tropes: i.e. additional text has been added to the preëxisting melody. The melismatic character of the Kyrie obviously favours this sort of farcing, but tropes on most other parts of the Mass are generally logogene: new verses—comprising both text and melody—have been interspersed between the phrases of the original chant, a practice that makes the nature of tropes as sung commentaries especially manifest.

This is the case for tropes on the Gloria in excelsis. The earliest recorded Gloria tropes date back to the 9th century, and through the course of the following centuries over a hundred examples thereof have been catalogued; it constitutes one of the largest trope repertoires after the Kyrie and Introit tropes. They were, howbeit, obsolescent by the 13th century, with one notable exception: the Spiritus et alme trope.

This set of verses grafted onto the Angelic Hymn is a relatively late composition, being first attested in Rouen MS. 1386 (U. 158), from Jumièges in Normandy, which dates to around 1100. These verses were associated with the melody of Gloria IX in the Vatican edition from the very beginning; indeed, this melody rarely appears in the earliest sources without the trope, which might indicate that it was originally composed for the Gloria thus farced. Indeed, this would explain why this particular melody has always been associated with Our Lady. Most Gloria trope verses were prone to melodic promiscuity, withal, and there are a few instances of the Spiritus et alme verses attached to other melodies, including Gloria IV, XIV, and XV.

From its birthplace in northern France, the Spiritus et alme trope spread to Aquitaine, England, and Italy, where it is attested in 12th century sources. In the following century, even as other Gloria tropes were falling into general disfavour, the Spiritus et alme verses continued to propagate relentlessly throughout Christendom, showing up in manuscripts from Spain, Portugal, Germany, Bohemia, Scandinavia, and Yugoslavia, where it even entered into the Old Slavonic use. The trope also appears in the liturgical books of various religious orders, including, fascinatingly enough, in ten Cistercian sources. The Order of Cîteaux’s approach to liturgy, as in other matters, was marked by an austere simplicity—one might even say by a certain Puritanism—wholly noxious to the flights of exuberant fancy that gave rise to tropes. Nevertheless, as Joaquim Bragança notes in his study of one of these sources, mediæval devotion to Our Lady—what Henry Adams called the “highest creative energy ever known to man”—was so powerful it could even vanquish the dour Cistercian hostility towards liturgical ornamentation.

|

|

|

|

The Gloria farced with the Spiritus et alme verses was the subject of polyphonic settings as well, including one for three voices with the Gloria IX melody as a tenor in the 12th-century Las Huelgas Codex (another Cistercian source, despite attempts by the Order to prohibit polyphony in its monasteries), two by Johannes Ciconia, and one by Guillaume Dufay. The composers of these works delighted in musically highlighting the Marian tropes, to the greater exaltation of Our Lady.

By the 15th century, then, the Spiritus et alme trope had become an established part of the Gloria in Masses on feasts and Saturdays of Our Lady nearly everywhere in Europe, featuring also in the pre-Tridentine printed editions of the Missale Romanum.

Alas, however, the Spiritus et alme trope fell afoul of the reforming humanist spirit that arose during this age, with its “tendency towards rationalism and desire for sobriety in Catholic worship” [1], and this would lead to its outright prohibition. On 20 July 1562, during the 22nd Session of the Council of Trent, a commission of seven prelates was appointed to examine the question of liturgical abuses. Among the Postulata nonnullorum patrum circa varios abusus in missis subinductos (Petitions by certain Fathers about various abuses introduced into Mass), one finds the following: “Let those additions Mariam gubernans, Mariam coronans be removed from the hymn Gloria in excelsis; they seem an unbefitting insertion” [2]. The members of the commission agreed that farcing the Gloria to extol Our Lady was unbefitting, and the memoir they presented to the papal legate Hercules Cardinal Gonzaga on 8 August 1562, under the heading Abusus, qui circa venerandum Missæ sacrificium evenire solent, partim a Patribus deputatis animadversi; partim ex multorum Prælatorum dictis, et scriptis excerpti (Abuses, which often occur during the venerable sacrifice of the Mass, in part noted by the delegated Fathers, in part taken from the sayings and writings of many Prelates), lists the “added words about the Blessed Virgin” as one of the abuses that had crept into the celebration of the Mass [3]. The commission called for the production of reformed missals purged of such putatively abusive accretions [4].

As a result, the Missale Romanum promulgated by Pope St Pius V in 1570 included a rubric forbidding the farcing of the Gloria, even in Masses of Our Lady [5]. The Spiritus et alme trope was therefore abandoned in all dioceses that adopted the Tridentine missal, and, having been smirched as an abuse, it also soon disappeared in those dioceses that kept their local uses as they reformed their books following the Tridentine model. The Parisian Missal ad formam Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini emendatum, for example, expunged the farced Marian Gloria and added the rubric Sic semper dicitur Gloria in excelsis.

The trope survived for a while in the extremely conservative Lyonese use, until its missal was reformed by Archbishop de Rochebonne in 1737 to bring it closer to the Tridentine model. It also remained in the use of Braga. In 1779, Archbishop Gaspar de Bragança, seeking to bring the Bragan use closer to the Roman, proposed, inter alia, the suppression of the Gloria de Domina, but was rebuffed by the chapter. The canons did deign to discuss the elimination of the Marian Gloria on 7 April 1780, but they finally decided to inform the subcantor and master of ceremonies that the Gloria was to be sung “according to the use of Braga”, thus preserving the trope. But finally, in 1924, a new edition of the Bragan Missal, approved by Pius XI, was promulgated which no longer included the farced Gloria, and thus disappeared its last vestige.

The Spiritus et alme trope represents a fascinating instance where the use of a trope was so popular and universal it nearly became an established part of the Roman rite. It raises intriguing questions about what ought to be considered a legitimate and organic development of the liturgy, and what constitutes an illegitimate accretion and abuse. Whatever the terse declarations of the Tridentine liturgical commission, it is hardly obvious that the Marian Gloria is a case of the latter, and one might be excused for considering its disappearance a matter for regret.

Notes

[1] Chadwick, Anthony J. “The Roman Missal of the Council of Trent” in T&T Clark Companion to Liturgy, ed. Alcuin Reid, 2016, p. 107.

[2] Ab hymno: Gloria in excelsis, tollantur illa additamenta: Mariam gubernans, Mariam coronans: quæ videntur inepte inculcari.

[3] Item forte essent animadvertenda in hymno Angelorum verba illa addita de Beata Virgine, Mariam gubernans, Mariam coronans ec.; videntur enim illa omnia inepte inculcari.

[4] Missalia secundum usum et veteram consuetudinem S. R. E. reformentur, omnibus iis, quæ clanculum irrepserunt, repurgatis, ut omni ex parte eadem pura, nitida et integra proponantur.

[5] Sic dicitur Gloria in excelsis etiam in missis beatę Marię. This rubric was dropped in the editio typica of the Roman Missal promulgated by Pope Benedict XV in 1920.

Reblogged this on In Ministerium Maiorum and commented:

From the invaluable Canticum Salomonis blog, some fascinating scholarship about the Roman liturgy. The real one. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person