Part 1: The French King as Bishop in the Use of the Royal Chapel at Versailles, 1

Part 2: The French King as Bishop in the Use of the Royal Chapel at Versailles, 2

Part III:

Modern Survivals of Royal Honors in the Liturgy of the Holy Sepulcher

Much of the glorious liturgical patrimony of the Gallican church—the stational processions, public penance, local chant traditions, the rich urban liturgy sustained by great beneficed clergy of the cathedral chapters—perished alongside the King in the revolutionary despoliations.

There is one place, however, where a curious relic of the honors once given to the bishop-king of France lives on: in Jerusalem. Many ancient practices have weathered the centuries under the hallowed dome of the Sepulcher, whose liturgical customs were essentially “frozen” in the 19th century by a series of consensus agreements between the six Churches, managed and enforced by the Ottoman authorities, and collectively called the Status Quo.

Designed to eliminate all future cause for disruption or dispute between the various Churches over possession of parts of the ancient basilica, it essentially means that, whatever the Greeks, Latins, Armenians, Syriac, Copts or Ethiopians were doing then—whatever shrines they possessed, feast days they celebrated, candles they lit—they must keep doing so in perpetuity, on penalty of breaking the agreement. Consequently, medieval practices like the Funerals of Christ and the morning-time Easter Vigil, vanished everywhere else in the Latin West, survive here by the iron force of custom, and valiant pilgrims may still attend midnight Matins with the Franciscans on feast days.

One such custom harks back all the way to the Royal Chapel of Versailles: the traditional honors given to the French Consul, formerly the French king’s official representative in the Protectorate of the Holy Land.

In a remarkable and puzzling anachronism, many of the ceremonial honors once offered to the French king in his palace at Versailles are still given to the Consul General of the French Republic on several occasions throughout the year, as a special recognition of France’s role in defending the Christian patrimony of the Holy Land.

Before approaching these fascinating glimpses into the past, a brief review of France’s role in the Holy Land is in order.

The Ottoman Period

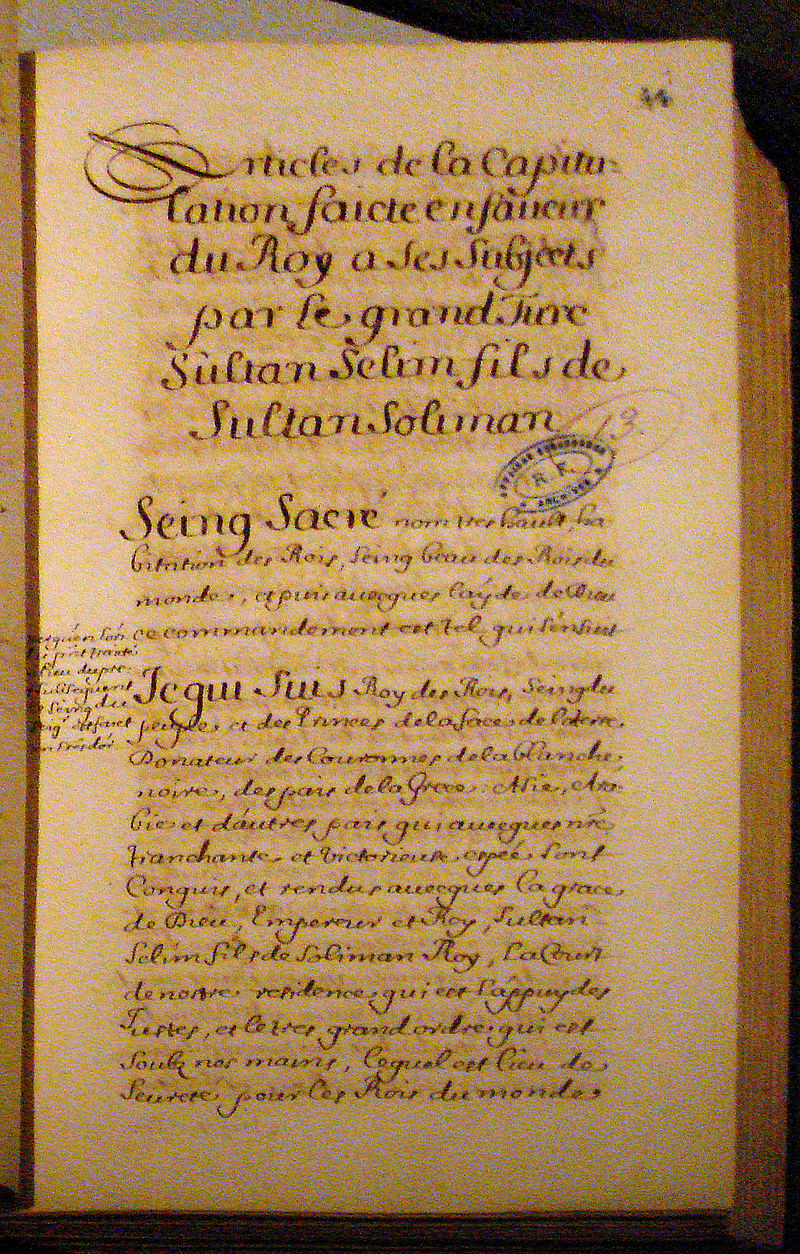

French interest in the Holy Land goes back, of course, to the Crusades and before, but the stable presence and advocacy of the French in the Levant began in the 16th century. The Capitulations between King Francis I and the Sublime Porte gave France special guardianship of all Christians (Latin and Greek) in the Holy Land and the entire Ottoman empire. Essentially, it put Christians under French legal patronage, so that Christian grievances could be aired by the French ambassador directly at the Ottoman court, and the ambassador in turn could negotiate ever more rights for missionaries and other French citizens. This was a distinguished role that, despite the waxing and waning of her influence, France never quite relinquished.

Subsequent Capitulations augmented French claims and led to the establishment of a French Protectorate over the Holy Land, with Louis XIV declaring himself the protector of Christians of all rites in the Ottoman Empire. French consuls resided first at Sidon and Alexandria, visiting Jerusalem in their circuits. Finally, in the nineteenth century, the French government established a French Consulate General in Jerusalem itself to manage the affairs of its citizens and to perform France’s traditional advocacy on behalf of Christians there.

The Franciscan custodians of the Holy Sepulcher began to offer liturgical honors to the consuls early on in their private chapels, as a token of gratitude and deference for their special role.[1] Some 19th century authors claim that these honors are directly based on the use of the Chapel, while others such as Santi are reticent about the obvious similarities.[2] When private chapels gave way to public churches at some point in this period of the consolidation of the Protectorate, the Franciscans continued to treat consuls with the same liturgical honors in all their Churches in the Levant, including the Holy Sepulcher.

For the French, this was an important sign of preeminence in the intense competition with other 19th century colonial powers. As Catherine Nicault argued, they were “carefully codified liturgical honors which made them the most eminent foreign dignitaries in Jerusalem.”[3]

In 1742, the Sacred Congregation intervened to codify the rite, acknowledging the honors but forbidding the kissing of the Gospel book:

- The Te Deum will be sung at the Consul’s entry into his duties

- A special place will be reserved for the Consul in the Church

- The Prefect will send a servant to inform the Consul at the time for Mass

- The Consul must not take the aspergillum from the priest’s hands, but the priest will approach with it and the Consul will take it with his finger at the end of the sponge. The priest will keep hold of the aspergillum.

- After genuflecting before the altar, the celebrant will bow toward the Consul before and after Mass

- The Consul will not be allowed to kiss the Gospel book

- The Consul will be incensed separately and the pax-brede will be given him to kiss

- The Consul will follow the procession holding a candle given him by one of the clergy

- On various special occasions, the prayer for the most Christian King will be said.

A Royal ordinance of 3 March 1781 countered, reaffirming the Consul’s exclusive right to a place of honor, to kiss the book, to receive the aspergillum from the priest’s own hand. Further, it made attendance at all Consular Masses obligatory for the Consul, Vice-Consul and his staff, on pain of a 30 livre fine (to be used for the redemption of slaves).

The Modern Period

After France’s aggressive secularization law of 1904, the French consul refused to continue to participate in these traditional ceremonies. The fate of royal honors seemed sealed when the fall of the Ottoman Empire, bringing with it the abolition of the Capitulations, abrogated France’s special privileges in the Levant.

The story of France’s tenacious attempts to retain the honors, to the irritation of the other Mandate powers, is told in fascinating detail by Catherine Nicault.

After fierce negotiations, the Holy See reached an accord with France on 4 December 1926 to reinstate the honors “in recognition of centuries of services rendered to Catholic individuals and communities of all nationalities in the Levant by the diplomats and consuls of France.”

The Accord permits the Consul all the usual honors and the right to sing Domine salvum fac Rem publicam, save for omitting the right to kiss the gospel book (already suppressed by the Congregation), the bows before and after Mass, and the right to sit in choir.[4] It does leave untouched, however, any local customs to the contrary.

Several decades later, the Franciscans decided to extend the honors to other officials representing Catholic countries traditionally offered protection to the Holy Land. These are, currently, Italy, Belgium, and Spain. Consequently, the French Consul is no longer the only state official to receive these special honors, and they have been diverged away from their origin in the use of the Royal Chapel.

The honors are given not only in the Sepulcher but in several Franciscan churches in the Holy Land, such as Beirut. I should also point out that the Eastern Rite and Orthodox Churches have their own tradition of consular liturgies and other honors, which are not discussed in this article, but may be studied in Santi’s Les Messes Consulaires.

The Honors

The honors in their present form consist principally in the rite of Solemn Entry and the ceremonial of consular Masses.

1) Solemn Entry

The first honor is the privilege of a solemn entry into the Holy Sepulcher, recalling the King’s reception by the Vincentian fathers of the Royal Chapel. According to Franciscan custom, it is otherwise reserved to cardinals.

Today, Consuls receive this solemn reception within thirty days of assuming their post. On 6th November 2019, the new Consul General of France, René Trocaz, made his solemn entry into the Holy Sepulcher. The consul walked in procession with a Franciscan cortege from Jaffa Gate to the Holy Sepulcher, and then to the French church of St. Anne, where a Te Deum was sung.

Official entry of new consul Pierre Cochard in 2016. The official booklet with rubrics and prayers for the event can be downloaded here.

2) Consular Masses

Besides the solemn entry, the Consul is present as a matter of protocol at two types of liturgies during his tenure: Consular Masses and Masses in the Presence of the Consul.

The protocol for these Masses is given on the website of the General Consulate:

1) A place of honor with prie-Dieu and carpet is reserved for the Consul General.

2) The Consul General is received at the door of the church by the clergy, who offer him holy water and conduct him to his place.

3) When he arrives at the altar, after his genuflexion the celebrant turns and bows to the Consul General.

4) After the Gospel is read by the deacon, he carries it to the Consul General (after the celebrant) to be kissed.

5) At the Offertory, the deacon incenses the Consul General immediately after the celebrant.

6) At the end of the Mass, after the Postcommunion the Domine salvam fac Rem publicam is sung twice (see above).

7) The celebrant bows to the Consul General before leaving the altar.

8) The clergy leads the Consul General to the door of the church.

9) In solemn processions when the Consul General is present, a place of honor is reserved for him immediately after the clergy. Upon entering or exiting the church, he is received and accompanied as described above.

10) When the Blessed Sacrament is exposed, the honors provided in 3, 5, and 8 are not given.

11) At Masses for the Dead, the honors provided in 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 are not given.

Some consular Masses are fixed, others vary each year. The Consulate website lists the schedule for 2017:

Consular Masses in 2017

4th February 2017 – Saint Maron. Maronite church.

April 2017 – Syrian Catholic Exarchate. Syriac Catholic church.

25th May 2017 – Ascension – Greek Catholic Exarchate. [Domaine de l’Eleona]

14th July 2017 – French national holiday. Basilica of St. Anne.

August 2017 – Armenian Catholic Exarchate. Armenian Catholic church.

11th August 2017 – Saint Clare. Convent of Poor Clares.

Masses in the presence of the Consul

6 January 2017 – Epiphany. Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem

3rd March 2017 – Crowning with Thorns. Ecce Homo.

16th April 2017 – Easter. Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher.

14th July 2016 (St. Anne’s)

14th July 2018 (St. Anne’s)

Conclusion: A curious anachronism?

Of course the question that begs to be asked is why the French state, rigorously secular, allows its representatives to take part in these ceremonies and receive these honors, and, in turn, why the Franciscans continue to render this homage to them. The Consulate’s website explains these honors in sympathetic detail, if in a way that distances the Consul from their religious implications:

As part of his required duties, the Consul General continues to assume the role of protector of several religious communities in accordance with treaties that were signed with the Ottomans and that have remained in force throughout the changes in states…In exchange, in the name of the Republic the Consul receives certain liturgical honors, such as the ceremony of his entry into the Holy Sepulcher, which recalls French protection over the holy sites, consular Masses, his presence in uniform at Christmas and Easter celebrations alongside other consuls from Catholic countries. If this religious role assumed by the Consul General has become less central, nevertheless it has its purpose: not only as a matter of tradition but also for the purpose of maintaining stable relations with the Christian community, whose future is always delicate and uncertain.[6]

The survival of this practice invites several interesting questions.

First of all, it is an open question, from a sacramental point of view, how honors exclusively reserved for the king in virtue of his quasi-sacramental ordination as Davidic King of France could be transferred to a diplomatic representative (of any stature) who has had no such anointing. Are there any other cases when royal honors are offered to an ambassador acting, so to speak, in persona regis? Honors given to the King and others in their capacity as members of the Order of the Holy Spirit do not seem like a relevant parallel, since they did not include such honors.

But in pure speculation let us assume that such a transfer were theoretically possible; namely, that royal honors could be given to the king’s agent in view of the quasi-episcopal ordination the king receives in his unction, in which the representative in some way participates. The fact is that today the Consuls, who might not even be baptized, no longer represent an ordained monarch but France’s secular head of an avowedly secular state born in bloody hatred of the Church.

In the final analysis, have the royal honors have become mere political protocol and historical curiosity, having lost their historical connection with France and the Royal Chapel, or even with the Catholic faith of France’s representatives?

Whatever the case may be, these ancient honors are a touching pre-revolutionary atavism, a reminder of the gesta Dei per Francos, when the Eldest Daughter of the Church bestirred herself in defense of the mother of all Churches, defending her siblings and vindicating the sovereign rights of God in heathen lands. The honors are no longer the outcome and the symbol of the protectorate, but first of all the memory of a past which no one can abolish.

NOTES:

[1] The ceremonies must have grown out of an understanding between the Franciscans and the French government over proper liturgical protocol for French representatives. The Archives of the Custody contain consular correspondence that indicates their attendance at Franciscan liturgies in Alexandria and Sidon, and their use of a special chair, e.g., in the Holy Sepulcher.

[2] P. Santi, Les messes consulaires des rites orientaux, Beirut, 1968

[3] Nicault, Catherine (1999). “The End of the French Religious Protectorate in Jerusalem (1918-1924)”. Bulletin du Centre Français de Jérusalem.

[4] The items of the Accord are as follows:

- a) The Representative of France will be invited to the solemn Mass

- b) a place of honor will be reserved for him outside and facing the choir. Nevertheless in churches where the French consuls’ chair is a fixed and immovable piece of the structure at the time of the signing of this Accord, the Representative of France will retain use of it, even if this chair is located inside the choir.

- b) the clergy will receive the Representative of France at the door of the Church, will offer him holy water and lead him to his place

- d) during the ceremony, the clergy will incense him before the others in attendance

- e) at the end of Mass the clergy will accompany him to the exit

[5] “Dans le cadre de sa circonscription, le Consul général continue à assumer un rôle de protection des communautés religieuses dans la ligne des accords signés avec les Ottomans, toujours en vigueur par le jeu de la succession d’États. À cette proposition diplomatique s’ajoutent des subventions, la mise à disposition de coopérants et, dans le cas des domaines nationaux, la prise en charge de l’entretien et du gardiennage. En échange, le Consul jouit, au nom de la République, des honneurs liturgiques, comme en témoignent la cérémonie de son entrée au Saint-Sépulcre qui rappelle la protection française sur les Lieux saints, les messes consulaires, ou encore sa présence en uniforme aux célébrations de Noël et de Pâques, aux côtés des autres consuls des pays catholiques. Si ce rôle religieux assumé par le Consul général devient moins central, il demeure utile non seulement eu égard à la tradition mais aussi au maintien d’équilibres communautaires délicats et à l’avenir toujours incertain des Chrétiens dans la région.” (Source: https://jerusalem.consulfrance.org/Histoire)