Several weeks ago we posted the last of our series of excerpts from the Voyages Liturgiques, a work that we hope has captured your imagination as much as it has ours. Happily there have been two grateful responses, one on New Liturgical Movement and on by the Rad Trad, both of them pointing out the role that cathedral chapters used to play in maintaining exemplary liturgical life in the Latin West.

I wanted to round out the series with a reflection of my own, pointing out some aspects of De Moléon’s authorial voice. Is he simply a liturgical tourist, a curiosity-seeker, or is his purpose more serious, or more sinister? Are the Voyages an amateur’s impressions, or a reformer’s manifesto?

Rarely does De Moléon actually express a direct opinion about the rites he observes—an occasional disparaging comment about medieval texts, a fastidious remark about “passing over” certain things he has found in older books. Much, however, is implied. In fact, the work is even more valuable once the reader realizes that its author is not an impartial observer. All told, when we count up what he decided to include, and what he must have excluded, and range together those aspects of liturgical life that seem to exercise the most fascination upon his imagination, we get a rather clear picture of a personality.

His personal “taste”—the first word of the preface, and a major theme of his century—largely governs what he includes in his account, and what he excludes. His clear prejudices and predilections shed an intriguing light on the character of the age, and of the reforming zeal that was brewing in the Gallican Church.

As any writer, De Moléon writes to please contemporary taste. His quest for “the most pure and ancient antiquity” in the cities and provinces of France was intended to flatter the antiquarian fancies of that century of Italian journeys and Versailles’ Apollonian king. The same taste leads him to admire survivals of the ceremonial splendor of the Middle Ages—pre-Mass processions, florid Tropes, Offertory verses, sanctuary veils, episcopal masses, etc.—as much as vestiges of Roman baths and funereal urns: he rejoices wherever he sniffs the sea-breeze of antiquity!

Yet, though the language of his Preface might seem to belie it, our traveler was seldom interested in the merely curious or antiquarian; his interest is more sure and mature than an aesthetic preoccupation with old ceremony.

I say this because, all told, he shows a keen preference for and understanding of the elements of integral liturgical life in the Roman tradition: survivals of the ancient baptismal rituals in the Easter Vigil, the full episcopal liturgy with assisting local clergy, the lives of observant and communal colleges and chapters, processions and stations, and in general all the colorful rituals of urban religious life that assimilated French towns to the world of the Ordo Romanus I. He either finds these things currently in use, and praises them; or through books finds them observed in centuries past, and lavishes his attention on the older state of affairs.

In each case, the picture that emerges, based partly on observations of contemporary practice, but also largely on ceremonies culled from ancient practice, is a sort of “classical ideal” for each city in question, a picture of its liturgical life at high tide, when the chapters were observant, the people wholeheartedly participating, and the liturgy fully integrated into urban life. We hasten to add that, in many cities covered in the Voyages, actual practice often strayed not too far behind this “classic ideal.”

Jungmann explains this spirit of the age well:

“The desire was to get free from all excess of emotions, free from all surfeit of forms; to get back again to ‘noble simplicity.’ As in contemporary art, where the model for this was sought in antiquity and attained in classicism, so in ecclesiastical life the model was perceived in the life of the ancient Church. And so a sort of Catholic classicism was arrived at, a sudden enthusiasm for the liturgical forms of primitive Christianity, forms which in many cases one believed could be taken over bodily, despite the interval of a thousand years and more, even though one was far removed from the spirit of that age” (MS, 152).

Because he rarely digresses to express his own opinions, it is not easy to tell what precisely our author admires in this “classic ideal,” nor why–at least, what is important is that it is ancient! But at first glance we can say he shows a sound taste for good principles, for the fully communal, urban episcopal liturgy, sung from memory, rife with public processions, blessings, sprinklings, and public acts of penance. There is much to commend in this vision.

However, the rationalist spirit of the age, already present in 16th-century liturgical commentary, is also apparent. For example, he frequently chastises the “mystics” for imposing senseless (if often “edifying”) explanations for ceremonies that really only have a simple literal causes. Like a less thorough-going Claude de Vert, he occasionally takes pains to expose the “genuine” literal sense. The arrangement of candles is usually to be explained by the need for light rather than any mystical reason (à la de Vert). This sometimes leads him to make rather bold claims, such as dismissing the whole ritual of extinguishing a symbolic number of candles during Tenebrae, as an irrational accident:

“However, far from extinguishing candles on these days when Matins begins at four in the afternoon, on the contrary they should have lighted them toward the evening, since light is more needed at that time than at four in the afternoon. This was not taken into account when people stopped saying this particular office near the end of night. Doubtless certain mystics who are ignorant of the true reasons for the institution of ceremonies will find some mysteries in these three days: as if they really thought that people acted differently on these three days than they did on every other day.”

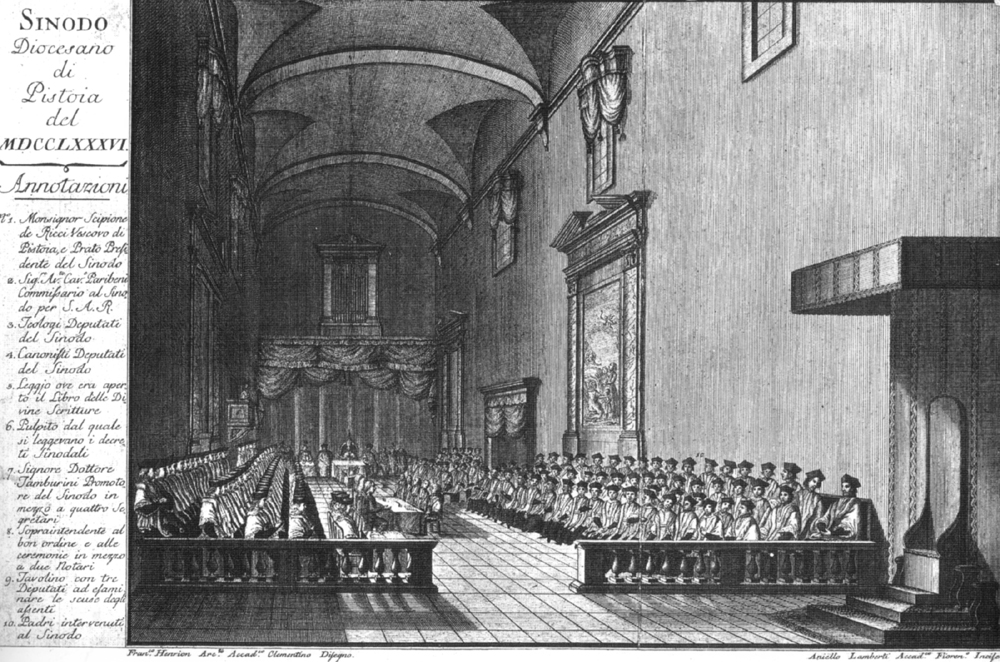

Several of his enlightened “talking points” seem to cast a long shadow toward the Synod of Pistoia (1786) and even to the post-conciliar reforms. How truly do De Moléon’s observations betray allegiance to contemporary Gallican liturgical reform projects, and to the general rationalist taste of his age? Surprisingly much.

For instance, his remarks show that he prefers the simple, unfurnished altar arrangement of antiquity, without retable, candles, or furnishings; the simple bishop’s chair in the center apse; he is fond of calling the altar the Table of Communion; the austere ritual of the Carthusians, he (wrongly) thinks, preserves the most ancient liturgical forms. Here is a list we made of elements he repeatedly, if indirectly circles about, indicating either his clear fascination or outright preference for them, so that they become “talking points” of his observations:

- The desirability of communion under two species; communion of priest and laity from the same Host

- The full Pre-mass procession with water blessing, sprinkling of the people, and visitation of the chapter house

- Candles: for lighting, not for mystical reasons.

- Afternoon Tenebrae is a irrational mistake.

- Ablutions that involve drinking water/wine used to rinse the fingers is unsanitary.

- The bishop’s chair should be simple and stand behind the altar in the apse, as in antiquity.

- Altars should be bare (no decoration, retable, candles) outside the celebration of Mass.

- The reredos is an innovation, and further breaks up visibility in the sanctuary.

- Prayers at the foot of the altar are a modern innovation.

- The Last Gospel is a modern innovation.

- The Carthusians preserve the most primitive uses.

- Full-length prostration on the ground is the true, ancient form of humiliation, not the more modern forms of kneeling or bowing.

- The excellence of the practice of expulsion and reconciliation of penitents during Lent

- Use of the Common Preface for Sundays of Lent is more ancient and logical, since they are not fasting days.

- He loves stations and processions of all kinds (Rogations, Lenten stations, etc), but mentions few devotions to saints.

- The Hours should be sung separately, as we find in ancient times, not in blocks.

- On fasting days, there should be no anticipation of Vespers.

- All should receive communion on Good Friday

- Mass in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament (and frequent exposition in general probably) is a modern innovation and inappropriate.

- Silent adoration is most fitting, without song or ceremony.

If we compare these points with the agenda of 17th and 18th-century French reformers, there are many parallels. Readers may recall that Voyages’ author was raised at the Abbey of Port-Royal itself, the capital of Jansenism. The ever censorious Guéranger himself accuses de Moléon directly of having been a Jansenist:

“(1718). Le Brun Desmarettes, acolyte, author of the breviaries of Orléans and Nevers. Under the pseudonym Sieur de Moléon, he wrote the interesting Voyages liturgiques de France, ou Recherches faites en diverses villes du royaume. Paris, 1718, in-8°. We owe the latest edition of the book of John of Avranches’ Liber de Officiis Ecclesiasticis to this Jansenist author” (Ins. lit. Vol. II, ch. 22, p. 479).

The fatal link between Jansenism and liturgical reform, which Guéranger was so keen to establish, has been challenged by later scholars. Guéranger tries to paint Jansenism as a crypto-Protestant movement and a haven for enlightened sceptics. This account is echoed by Geoffrey Hull “The Proto-History of the Roman Liturgical Reform,” where he explains the Jansenist liturgical project. In a word, the Jansenists’

“habit of regarding Saint Augustine as a theological oracle led them to idolize the Church of the age in which he lived, the fifth century. If Catholics ought to follow the teachings of Saint Augustine…then they should also seek to emulate in their churches the worship of this golden age of Christianity. Hence the heretics’ contempt for the theology and liturgy of the Middle Ages.”

Modern historians are more cautious in their assessments of Jansenism as a movement. What is still a consensus view, however, is that the Gallican Church as a whole was strongly antiquarian.

The supposed Jansenists and the antiquarians are both united in their attempt to return to a perceived golden age of ecclesiastical discipline and practice, rejecting what they suspected to have originated in the Middle Ages and especially those ages’ contributions to the liturgical tradition. De Moléon more than once “declines to comment” on practices he finds in medieval ordinals; he wishes that the body of tropes might disappear because of their poor literary quality. The Jansenists’ famous austerity made them partial to severe penances: hence their attempts to restore public penitential rituals like that of Rouen, on which our author lavishes so much attention. De Moléon’s fascination with prostration could be noted here: it approaches the bizarre.

Unlike Protestants, Jansenists and enlightened archeologists did not deny the mystery of the Eucharist or the worship due to it, only wishing for a more moderate use of adoration. They did not deny the distinction between the ministerial and common priesthood, and the Voyages show no indication that there is any unhealthy “separation” between the people and the ministers. De Moléon says little about the people save for frequent observations to the effect of their enthusiastic participation in the liturgical customs of their city. He does not suggest that rood screens or silent canons or the Latin language is a barrier to this participation. Later reformers did aim to make the laity participate more directly in the ceremonies, singing the ordinary along with the priest, printing vernacular missals, removing rood screens, and eliminating silent parts, but such ambitions are not apparent in the Voyages.

So, what are we to say? How right was Guéranger? In my opinion, even while eschewing medieval commentary and some particular rituals, on the whole our traveler admires the contemporary liturgical life of France as a faithful expression of “the most pure and ancient antiquity.” There is only a faint trace of Jungmann’s thorough distaste for the “wild overgrowth” of the “Gothic,” or the inveterate laicism that would characterize later 20th century writers. At least overtly, he does not float in the same channel as Quesnel, De Vert, and other contemporary reformers, though he may be skirting the same banks. On the whole, the picture he paints is of a French people who are deeply engaged in their liturgical life and cathedral chapters that observe the whole office. His “taste” is for antiquity and ceremonial splendor, and this leads him to admire the pontifical liturgies of the middle ages. Admittedly, perhaps he does so because he believes them to be much more ancient than the extant source-books: expressions of the most ancient Gallic liturgies.

On many points I would look like a jansenist if I lived during that time. For instance, I also think that mass in the presence of the blessed sacrament is a bit..off. But then again, many saints didnt have any problems with that, and in fact, they nourished their faith with all those things that jansenists dislike.. So maybe the best approach is simply to focus on God and follow the path the Church is travelling on without reasoning too much on what is ’noble simplicity’.

What do you think of Claude Fleury? If you have ever come across his works? Is he also leaning towards Jansenism?

LikeLike