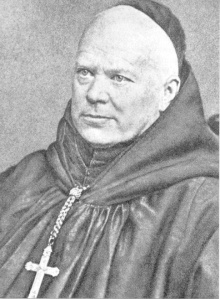

As a follow-up to our post about Pope Alexander VII’s brief Ad aures nostras condemning de Voisin’s translation of the missal for use by the laity, and Lebrun’s defence of such translations, we herewith post a translation of Dom Prosper Guéranger’s reflexions on the matter in volume 2 of his Institutions liturgiques.

Guéranger has been called the “father of the Liturgical Movement”: although the movement proper actually began in the 20th century through the efforts of Dom Lambert Beauduin, Guéranger did pioneer the rediscovery of liturgical piety and worked tirelessly to restore the liturgy to the centre of Christian life, through works like the Institutions liturgiques, written for use by seminarians and clergymen, and L’année liturgique, aimed at the general public. As one sees in the latter work, however, Guéranger refused to print a literal translation of the Roman Canon. He interpreted Ad aures nostras not as addressing particular problems of the 17th century French church, but as a general prohibition on full literal translations of the missal.

Guéranger was keenly aware of the importance of veiling in the liturgy, through which it expresses mystery and revelation (cf. Martin Mosebach, “Revelation Through Veiling in the Old Roman Catholic Liturgy” in The Heresy of Formlessness), and the use of Latin (and the silent Canon) is one of the foremost of these “veils”.

In the excerpt reproduced below, Guéranger warns against allowing the uneducated to have full access to the literal words of the holiest of the Church’s prayers, for it would constitute a rupture of this veil. He alludes to the disastrous consequences that easy access to literal translations of Holy Scripture had during and after the Protestant Revolt, and concludes with poses the rhetorical question: if it is so important that the laity be able to follow what the priest says during Mass word by word, why not just have Mass in the vernacular?

Any Catholic can doubtlessly see, given the gravity of the Roman Pontiff’s language, that [the translation of the Missal] was a grave matter, but more than one of our readers will perhaps be shocked, after what we have just reported, at the indifference wherewith an abuse which so aroused the zeal of Alexander VII is treated to-day. In our times, all the faithful in France, as long as they can read, can scrutinize the most mysterious parts of the Canon of the Mass thanks to the innumerable and ubiquitous translations thereof; and the Bible, in the vulgar tongue, is everywhere placed at their disposal. What are we to think about this state of affairs?

There is no need to bother Rome with the question: many a time, after Alexander VII, she has expressed herself so clearly as to leave no room for doubt. Yet let us keep in mind that the councils of the last three centuries have declared that the use of translations of Holy Scripture—as long as they are not accompanied by a gloss or notes drawn from the Church Fathers and the teachings of tradition—is illicit, and, on the authority of the Holy See and the clergy of France, we aver that any translation of the Canon of the Mass not accompanied by a commentary addressing any difficulties is akin to those prohibited translation of Scripture.

[…]

[On the argument that vernacular translations were necessary to facilitate the conversion of Protestants after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.]

Could there really have been no alternative but an outright translation of the Canon of the Mass? Was it necessary to ignore the prescriptions of the Holy See and the Council of Trent, when it is so easy to attach to the text a commentary putting an end to all objections, a gloss that prevents the eye of a profane and illiterate reader to pierce the shadows that protect the mysteries against his curiosity, as is done everywhere except France?

From the moment the people can read in their own tongue, word by word, what the priest recites at the altar, why should the latter use a foreign language which at that point no longer hides anything? Why should he recite in a low voice what the lowliest charwoman or the coarsest drudge can follow and know as well as he? Those audacious proponents of the anti-liturgical heresy did not neglect to take advantage of these two terrible consequences, as we shall see in the rest of this story.

Tout catholique verra, sans doute, à la gravité du langage du Pontife romain, qu’il s’agissait dans cette occasion d’une affaire majeure ; mais plus d’un de nos lecteurs s’étonnera, peut-être, après ce que nous venons de rapporter, de l’insensibilité avec laquelle on considère aujourd’hui un abus qui excitait à un si haut degré le zèle d’Alexandre VII. Aujourd’hui, tous les fidèles de France, pour peu qu’ils sachent lire, sont à même de scruter ce qu’il y a de plus mystérieux dans le canon de la messe, grâce aux innombrables traductions qui en sont répandues en tous lieux ; la Bible, en langue vulgaire est, de toutes parts, mise à leur disposition : que doit-on penser de cet état de choses ? Certes, ce n’est pas à Rome que nous le demanderons : bien des fois, depuis Alexandre VII, elle s’est exprimée de manière à ne nous laisser aucun doute; mais nous dirons avec tous les conciles des trois derniers siècles, que l’usage des traductions de l’Écriture sainte, tant qu’elles ne sont pas accompagnées d’une glose ou de notes tirées des saints Pères et des enseignements de la tradition, sont illicites, et, avec l’autorité du Saint-Siège et du clergé de France, nous assimilerons aux versions de l’Écriture prohibées, toute traduction du canon de la messe qui serait pas accompagnée d’un commentaire qui prévienne les difficultés.

[…] Mais n’y avait-il pas d’autre mesure qu’une traduction pure et simple du canon de la messe ? fallait-il compter pour rien les prescriptions du Saint-Siège, du concile de Trente, lorsqu’on avait le moyen si facile et mis en usage en tous lieux, excepté en France, de joindre au texte un commentaire qui arrête les objections, une glose qui ne permet pas que l’œil du lecteur profane et illettré perce des ombres qui garantissent les mystères contre sa curiosité. Du moment que le peuple peut lire en sa langue, mot pour mot, ce que le prêtre récite à l’autel, pourquoi ce dernier use-t-il d’une langue étrangère qui dès lors ne cache plus rien ? pourquoi récite-t-il à voix basse ce que la dernière servante, le plus grossier manœuvre suivent de l’œil et peuvent connaître aussi bien que lui ? Deux conséquences terribles que nos docteurs antiliturgistes ne manqueront pas de tirer avec toute leur audace, ainsi qu’on le verra dans la suite de ce récit.

One thought on “Dom Guéranger on Translating the Missal”