When, on the Ides of July of the year of the most fructiferous Incarnation of Our Lord 1099, after nearly four years of bellicose pilgrimage and a month-long exhausting siege, the Crusaders finally broke through the inner ramparts of Jerusalem and poured into the holy city, freeing it from centuries-long occupation by the Mohammedan horde, their surpassing joy could only find liturgical expression in the office of Easter Day, which was celebrated, however out of season, in the church of the Holy Sepulchre. Hæc dies quam fecit Dominus, exsultemus et lætemur in ea—the words of the Gradual resounded in that venerable basilica, as Raymond of Aguilers, chaplain of the Lord Raymond of Saint-Gilles, Count of Toulouse and later Count of Tripoli, recounts in his Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem. The mediæval mind easily understood the deliverance of Jerusalem from the infidels as a type of the deliverance of mankind in Our Lord’s glorious Resurrection; a new day, demanding a canticum novum. Raymond’s fond memories of the event wax exuberant in his chronicle:

A new day, a new joy, and new and perpetual delight! The fulfilment of labour and devotion: new words, new songs were sounded forth by all. This day, I say, which shall be celebrated for centuries to come, transformed our pains and travails into joy and exultation. This day, I say, was the harrowing of all heathendom, the consolation of Christendom, the renewal of our faith. “This is the day which the Lord hath made: let us be glad and rejoice therein”, for therein the Lord illumined and blessed His people. […] This day, the Ides of July, shall be celebrated to the praise and glory of God’s name […] In this day we sang the office of the Resurrection, for on this day, He Who arose from the dead by His power, uplifted us by His grace. 1

In the ensuing octave, the triumphant knights roamed around the holy places of the city, venerating the relics, singing psalms, hymns, and spiritual canticles, and they solemnly celebrated the Octave Day on 22 July, choosing the worthy Godfrey of Bouillon as their ruler. They thenceforth established 15 July as a liturgical feast day to commemorate the liberation of the holy city, as the chroniclers attest, among them William of Tyre, e.g.:

In order that the memory of this great deed might be better preserved, a general decree was issued which met with the approval and sanction of all. It was ordained that this day be held sacred and set apart from all others as the time when, for the glory and praise of the Christian name, there should be recounted all that had been foretold by the prophets concerning this event. On this day intercession should always be made to the Lord for the souls of those by whose commendable and successful labours the city beloved of God had been restored to the ancient freedom of the Christian faith. 2

Early in Godfrey’s reign, a canonical chapter was established in the church of the Holy Sepulchre, and a proper liturgical use slowly developed, especially after that body was reformed and placed under the Augustinian rule in 1114. The use of the Holy Sepulchre was based, as one would expect given the origin of its immigrant churchmen, mostly on northern French uses, especially those of Chartres, Bayeux, Évreux, and Séez. This use would in turn form the basis of those of the religious orders that emanated from the Holy Land, including the Carmelites and the Knights Templar and Hospitaller.

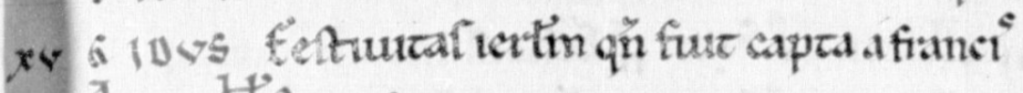

The liturgical sources variously dub the feast of 15 July the Festivitas sancte hierusalem, or Festivitas hierusalem quando capta fuit a Christianis (or a Francis), or In liberatione sancte civitatis Ierusalem (de manibus turchorum). The admirable victory of the First Crusade was thus fixed into the framework of the history of salvation, being both the fulfilment of prophecies, as William of Tyre states in the aforesaid excerpt, and the anagogical harbinger of the ultimate victory: the Christians’ entry into the heavenly Jerusalem.

The Mass opens with the famous introit borrowed from the Fourth Sunday of Lent: Letare Iherusalem et conventum facite omnes qui diligitis eam, gaudete cum leticia, qui in tristicia fuistis, ut exultetis, et saciemini ab uberibus consolacionis vestre, with the verse from the eminently apposite psalm 121. Preaching on this feast day shortly after the reconquest, Fulcher of Chartres repeated these verses from Isaias, and gave the continuation of the prophecy, concluding with the declaration that the Crusader triumph was its fulfilment: Hec omnia oculis nostris vidimus. Ekkehard of Aura agreed that the prophecy applied to the epic of the Crusaders, writing (rather abstrusely):

These, and a thousand other prognostics of the sort, albeit that they refer through anagogy to what is above—our mother Jerusalem—encourage the weaker members, who have drunk from the breasts of the consolation of those things written and to be written, to undergo dangers even historically by an actual journey because of such a contemplation or partaking in joy3.

William of Tyre, too, claimed the reconquest of Jerusalem was the literal fulfilment of Isaias’ oracle: ita ut illud prophete impletum ad litteram videretur oraculum «letamini cum Ierusalem et exultate in ea omnes qui diligitis eam».

But by fulfilling the ancient prophecy, the victory of 15 July itself became the type of a more lasting kind of victory. The very use of an Advent introit points to the Second Coming, and the collect, secret, and postcommunion emphasize this eschatological theme:

Collect: Almighty God, who by thy marvellous strength hast torn thy city Jerusalem from the hands of the paynims and restored it to the Christians, help us in thy mercy, we beseech thee, and grant that we who with yearly devotion celebrate this solemnity may deserve to attain the joys of the heavenly Jerusalem. Through our Lord, &c. (Omnipotens Deus, qui virtute tua mirabili Ierusalem civitatem tuam de manu paganorum eruisti et Christianis reddidisti, adesto, quesumus, nobis propitius, et concede ut qui hanc sollennitatem annua recolimus devotione, ad superne Ierusalem gaudia pervenire mereamur. Per Dominum.)

Secret: Mercifully accept, O Lord, we beseech thee, this host which we humbly offer thee, and make us worthy of its mystery, that we who celebrate this day when the city of Jerusalem was freed from the hands of the paynim may at last deserve to become fellow-citizens of the heavenly Jerusalem. Through our Lord, &c. (Hanc, Domine, quesumus, hostiam quam tibi supplices offerimus dignanter suscipe, et eius misterio nos dignos effice, ut qui de Ierusalem civitate de manu paganorum eruta hunc diem agimus celebrem, celestis Ierusalem concives fieri tandem mereamur. Per Dominum.)

Postcommunion: May the sacrifice we have received, O Lord, profit to the salvation of our body and soul, so that we who rejoice in the liberty of thy city Jerusalem may deserve to be counted heirs of the heavenly Jerusalem. Through our Lord, &c. (Quod sumpsimus, Domine, sacrificium ad corporis et anime nobis proficiat salutem, ut qui de civitatis tue Ierusalem libertate gaudemus, in celesti Ierusalem hereditari mereamur. Per Dominum.)

The Epistle pericope is Isaias 60, 1-6 (“Arise, be enlightened, O Jerusalem: for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee” &c.), the first line whereof forms the verse of the Gradual, Omnes de Saba, taken from the feast of the Epiphany. Ekkehard mentions this passage together with that of the introit as one of prophecies that the Crusaders’ feat had made “visible history”4. The Alleluia responsory, which seems to have fluctuated between Te decet hymnus and Qui confidunt, both lifted from Sundays after Pentecost, are taken from psalm verses germane to the liberation of Jerusalem. This was followed by a brash sequence, Manu plaudant, which will have to be discussed in a future post.

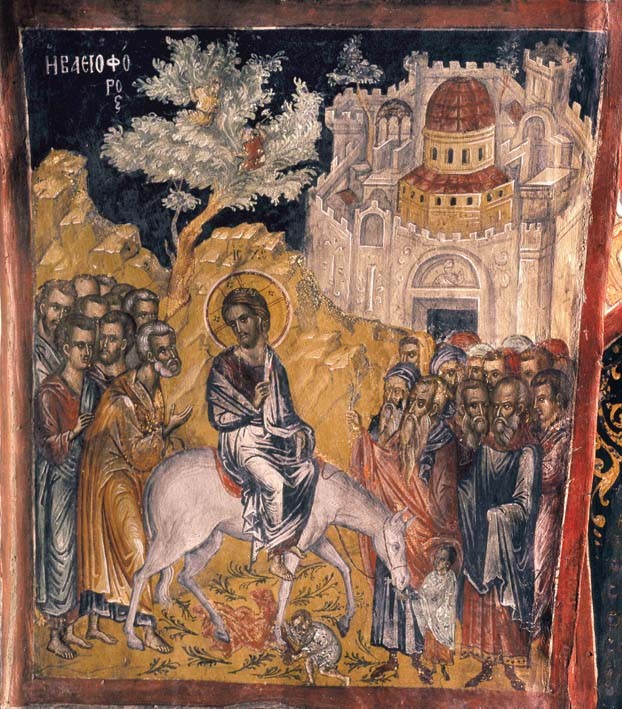

The Gospel lesson comes from Matthew 21, 1-9: Our Lord’s glorious entry into Jerusalem before His Passion, acclaimed as the Son of David by the Hebrew children. The pugnacious Offertory of the Third Sunday after Epiphany, Dextera Domini fecit virtutem, was chaunted thereafter and, during communion, the antiphon from the Second Sunday in Advent: “Arise, O Jerusalem, and stand on high: and behold the joy that cometh to thee from God.”

As the church of the Holy Sepulchre grew too small for the needs of the new Crusader Kingdom, and as it merited embellishment in any case, a considerable rebuilding was undertaken which concluded with the re-dedication of the church on 15 July 1149, the quinquagenary of the liberation, by the Lord Fulcher of Angoulême, Patriarch of Jerusalem. This prelate seems to have undertaken some revision of the Latin Jerusalemite liturgy, which especially affected the 15 July, now the bicephalous celebration of both the liberation and the dedication of the church of the Holy Sepulchre—Liberatio sancti civitatis Iherusalem de manibus Turchorum et Dedicatio ecclesie domnici sepulcri—with two Masses and Offices. In the basilica itself, the Dedication seems to have been celebrated exclusively, except for the morrow-mass, which was that of the Liberation. The collect of the Liberation, however was changed: “Almighty and everlasting God, builder and guardian of the heavenly city of Jerusalem, protect from on high this place with its inhabitants, that it might be in itself an abode of safety and peace”4; this was borrowed from a preëxisting collect. The change of focus of this new collect is also evinced by the introduction of antiphons into the Office borrowed from the office of the Dedication that tended to refer to the dignity of the church of the Holy Sepulchre rather than the glorious liberation of the city.

The ordinals indicate that in the basilica a festive procession took place after the morrow-mass of the Liberation; whether this was introduced with the 1149 revisions or was a continuation of an earlier practice is unknown. The procession set out from the church of the Holy Sepulchre to the Temple, and upon arriving at its entrance they sang prayers taken from the office of the Dedication. They then set forth to the “place where the city was captured”, i.e. the place where the wall was breached on 15 July 1099, and held another station, a sermon was preached, and a blessing given; perhaps the sermon by Fulcher of Chartres mentioned above was delivered in these circumstances. Thus the procession connected the Old Testament (the Temple) with the New (the Holy Sepulchre) and with the Crusader victory (the city wall). Finally the canons and the faithful returned to the Holy Sepulchre for Tierce. The rest of the office in the basilica was composed mainly from elements taken from the office of the Dedication according to the use of Chartres. One presumes, however, that in the other churches of the diocese of Jerusalem the Mass and Office of the Liberation were celebrated instead.

Alas, Christian rule of Jerusalem did not last the century. In 1187, the city fell to Saladin, and, although the liturgical use of the Holy Sepulchre survived in the remainder of the Crusader states and within certain religious orders, the celebration of the feasts of the Liberation of Jerusalem and the Dedication of the Holy Sepulchre seem to have been mostly abandoned. It only reappears in one manuscript after 1187, which dates from the odd episode when Jerusalem briefly returned to Christian hands thanks to the machinations of the excommunicate Emperor Frederick II. In this manuscript, the Mass is entitled Missa pro libertate ierusalem de manu paganorum, and the Gospel pericope from Matthew 21 has been replaced with the verses in Luke 19 wherein Our Lord weeps for Jerusalem. It has therefore been argued, with undeniable verisimilitude, that the old Liberation Mass was transformed into a Mass to ask for the recapture of Jerusalem. But in any case, even this proved short-lived.

Although notices marking the liberation of Jerusalem on 15 July appear in the kalendars of several Western liturgical books, few Western churches adopted the feast as it was celebrated in Jerusalem. It does appear in a 14th century missal from the Hospitaller priory in Autun, under the title In festo deliberacionis Iherusalem. Liturgical books from Tours, Nantes, and the Abbeys of St Mesmin (near Orléans) and Beaulieu (near Loches) feature a feast of the Holy Sepulchre on 15 July, although it does not make explicit reference to the Liberation, and its propers antedated the First Crusade. A feast for the Liberatio Iherusalem appears with a Mass and Office in liturgical books from the cathedral of St Étienne of Bourges dating from the 13th to the 15th centuries. Its propers are composed of elements from office of the Dedication and also from the Easter liturgy: a fascinating reminder of the Paschal joy that seized the Crusaders on those happy Ides of July 1099.

Our hearty acknowledgements to the reader who provided us with some of the necessary bibliographic material for this post.

Notes

1. Nova dies, novum gaudium, nova et perpetua leticia; laboris atque devotionis consummatio, nova verba nova cantica, ab universis exigebat. Hęc, inquam, dies celebris in omni seculo venturo, omnes dolores atque labores gaudium et exultationem fecit. Dies hęc, inquam, tocius paganitatis exinanicio, christianitatis confirmatio, et fidei nostrae renovatio. Hęc dies quam fecit Dominus, exultemus et letemur in ea, quia in hac illuxit et benedixit Dominus populo suo […] Hęc dies celebratur Idus Iulii, ad laudem et gloriam nominis Christi. […] In hac die cantavimus officium de resurrectione, quia in hac die ille qui sua virtute a mortuis resurrexit, per gratiam suam nos resuscitavit.

2. Ad maiorem autem tanti facti memoriam ex communi decreto sancitum omnium voto susceptum et approbatum est, ut hic dies apud omnes solemnis et inter celebres celebrior perpetuo haberetur, in qua, ad laudem et gloriam nominis christiani, quicquid in prophetis de hoc facto quasi vaticinium predictum fuerat, referatur: et pro eorum animabus fiat ad Dominum intercessio, quorum labore commendabili et favorabili apud omnes predicta Deo amabilis civitas et fidei christiane et pristine restituta est libertati.

3. Hec et huiusmodi mille pesagia licet per anagogen ad illam quę sursum est matrem nostram Hierusalem referantur, tamen infirmioribus membris ab uberibus consolationis prescriptę vel scribende potatis pro tanti contemplatione vel participatione gaudii periculis se tradere etiam hystorialiter practica discursione cohortantur.

4. Versis in hystorias visibiles eatenus mysticis prophetiis.

5. Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, edificator et custos Iherusalem civitatis superne, custodi locum istum cum habitatoribus suis: ut sit in eo domicilium incolumitatis et pacis. Per Dominum.

2 thoughts on “Crusader Liturgy: The Feast of the Liberation of Jerusalem”