Although in promulgating the Tridentine books St Pius V made it clear proper liturgical uses of proven antiquity were to survive,[1] a centralizing Spirit of the Council of Trent nevertheless did lead to the suffocation of many such venerable uses. The Cistercian use is one example, and Archdale King here tells the turbulent story of its vicissitudes in the wake of the Pian reform.

An excerpt from Liturgies of the Religious Orders by Archdale A. King, The Bruce Publishing Co., 1955.

The continued existence of the traditional rite of the Order was never threatened by the reforming activities of St Pius V (1566-1572). The bull Quo primum tempore (1570) expressly approved the use of liturgies which would show a continuous usage of at least two hundred years, and that of the Cistercians had been in existence for four hundred. It was not, therefore, a privilege that the Pope granted when he confirmed the Cistercian use, but rather a right that he respected.[2] The constitution Ex innumeris curis (1570), which was addressed to the Cistercians, affirmed that the Order should preserve its liturgy intact both for Mass and Office. It desired “the whole Order to celebrate the holy Sacrifice of the Mass and all the offices of the day and night according to the rite proper to the Order.”[3] Two years previously, the same holy Pontiff had informed the Congregation of Castile in the bull Intra cordis (25 October 1568) that his liturgical reform concerned only those churches and religious houses in which the Office should be, or had been, celebrated according to the rite of the Roman Church. Pius IX (1846-1878), recalling his saintly predecessor, said that it was altogether lawful (jure inde ac merito) for the illustrious Cistercian family to maintain intact its liturgical tradition:[4] an opinion confirmed by the Congregation of Rites on 8 March 1913.

Such indeed may be Rome’s views on the question, but there had been, three centuries before, a general abandonment of Cistercian liturgical formulas at the behest of religious who desired “novelty” rather than tradition.[5]

As early as 1573 Wettingen and Marienstadt had already adopted the Roman rite as exemplified in the books of the Pian reform, although in that very year we find the abbot of Cîteaux, Nicholas I Boucherat, visiting houses in Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Belgium, and Luxemburg, in all of which he impressed upon the religious their duty to maintain the rite proper to the Order.[6] His successor, Edme de la Croix, was invited by the general chapter of 1601 to write a treatise on the Cistercian liturgy, but the “landslide” could not be averted. Several houses had already discontinued the O Salutaris after the consecration and the psalm Laetatus sum after the Pater noster in the Mass. The chapter of 1601 had made it clear that the old rite was to be maintained,[7] but love of novelty proved too strong, and the “reforming” work was accelerated.

Two abbots of Cîteaux stand out in respect to the so-called “reform”: Nicholas II Boucherat (1604-1625), under whom the axe was laid at the root of the traditional rite, and Claude Vaussin (1643-1670), who gathered up the fragments that remained in the liturgical books at present in use.

The general chapter of 1605 passed a number of disquieting measures which legalized various Roman practices. Nicholas II seems to have been authorized to draw up a statement on the traditional rite, but the statutes that were passed showed clearly the trend of events, and we find by way of a preface: Ut Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae, quoad fieri potest, conformetur, deinceps… The concessions included the suppression of the Alleluia in the time of Septuagesima, use of the Roman martyrology until a new Cistercian edition is forthcoming, suppression of the daily Mass for the dead on Sundays and feasts of sermon and of the Apostles, the adoption of all the Roman feasts in the calendar, and permission for those in Poland and Prussia, who say Mass outside the enclosure, to follow the Roman ordo missae.[8]

A first move in the alteration of the liturgical texts appears to have come from the Congregation of Lombardy and Tuscany, which produced a Romanized breviary at Venice in 1608, in which the three last days of Holy Week were simply and solely the Roman office. The book received the approbation, not only of the general chapter of the Congregation, but also of the abbot of Cîteaux. Changes became well-nigh universal in the Order, and the general chapter of 1609 is forced to admit that the uniformity of rite prescribed in the Charter of Charity exists no longer, save in a few houses: quod tamen paucis in monasteriis observatur.

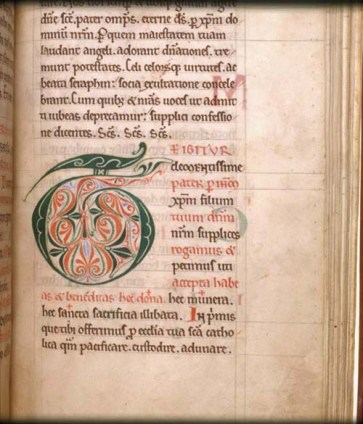

A final attempt was made to save the traditional liturgy, and restore the broken unity: intermissam unitatem restituere cupiens. The general chapter ordered a revision of the liber usuum,[9] with John Martienne, abbot of Cherlieu, as editor, and also the insertion of the ordinarium missae at the beginning of the missal, together with a repeal of the permission to celebrate Mass according to the Roman ordo missae.[10] Ancient Cistercian missals did not have a ritus servandus in celebratione missarum,[11] and it was prescribed for the first time in 1609: Ritus missarum juxta Ordinis consuetudinuem celebrandarum excure et accurate descriptus ac initio Missalium de caetero praeponendus. The decree was never put into force, save later in the Congregation of Castile, and the ordo missae in the missal of 1617 was taken from the Roman rite.[12]

The forces of the liturgical “modernists” were too strong for the traditionalists, and the Romanizing of the liturgy proceeded without serious interruption.

In 1611, religious of the Order were permitted to say private Masses according to the Roman rubrics, and in the same year the general chapter of the Italian Feuillants (Congregation of St Bernard), held at Pignerol in Piedmont, decided to “reform” their breviary. Other members of the Order wished to adopt the monastic breviary, which had been authorized by Pope Paul V in 1612.

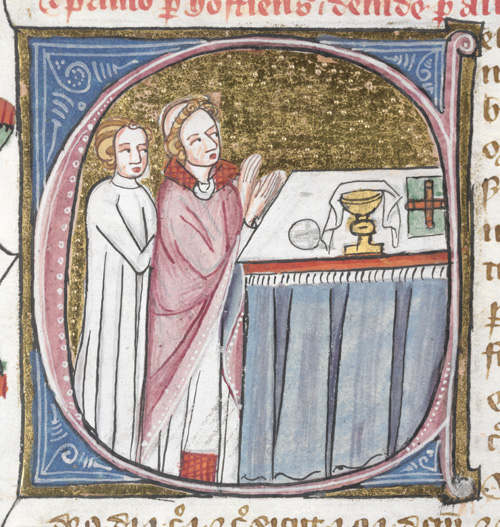

Permission was given by the general chapter and the abbot of Cîteaux for Mass to be celebrated juxta ritum romanum, and in 1617 a breviary and a missal appeared for the use of the whole Order. It was the last time that a liturgical book was to have so wide a circulation. The breviary was largely the same as the Lombard breviary of 1608, with the Roman office for the Triduum sacrum in place of the Cistercian office. The traditional rite was, in the main, preserved, but the book lacked harmony and unity. As for the missal,[13] the Roman rubrics were amplified, prayers before and after Mass were added, and the ritus celebrandi inserted: Ritus celebrandi Missam secundum usum Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae in gratiam illorum religiosorum Ordinis nostri Cisterciensis, hic inserti, quibus eorundem utendorum a RR. D. nostro Generali Cisterciensi aut Capitulo ejusdem Ordinis generali facta fuerit potestas.

The repudiation of the traditional rite was consummated in the following year (1618), and the general chapter formally adopted the Roman ritus celebrandi:

Henceforth it is ordered that both conventual and private Mass will be celebrated according to the Roman rite and ceremonies by all abbots and monks without exception. Wherefore, let the psalm Judica me, Deus, the Confiteor, and other things be said as described in the Roman rite. The Missal and Office of the Order, however, shall be retained, except that the psalm Laetatus sum and the collects associated thereto shall be omitted.[14]

The same general chapter ordered, also, the text of the lectionary to conform to that of the Roman breviary.

Hard and unjust things were said about the ancient liturgy, and in 1622 St. Francis de Sales, when acting as president at the general chapter of the Feuillants, openly advocated the adoption of the reformed Roman breviary. He said that the “offensive, childish, and obscure” parts of the old Cistercian texts were incompatible with the dignity of the Church.[15] In 1623, the general chapter of Cîteaux discussed the question of the correction of the breviary, but it was decided that no substantial changes were to be made: ita tamen ut essentialia remaneant.[16] In 1626 the traditional psalter was replaced by a form of the Sexto-Clementine Vulgate.[17] Liturgical unrest was in the air, and editions of the breviary appeared in 1627, 1641, 1646, and 1648: precision, order, and harmony were sadly lacking. A new edition of the missal, sponsored by Cardinal Richelieu, commendatory abbot of Cîteaux, was printed in 1643. Feelings ran high, and the authority of the general chapter was considerably weakened by the existence of independent Congregations.

The constant liturgical changes in the time of Nicholas II had produced the greatest confusion, and it was left to Claude Vaussin, who was elected in 1645, to produce liturgical books that would be definitive and permanent. The general chapter of 1651 accepted the principle of a new reform, and appointed a commission for the purpose.[18] The Romeward trend had gone too far to admit of a return to the status quo ante, and the Congregation of Rites had encouraged houses to adopt the Pian books which were considerably shorter than those of the Order. In the first place, Dom Claude was faced with the problem, how was it possible to harmonize the Cistercian consuetudines with the Roman rubrics? The result would necessarily be a hybrid, which has been well described by a Cistercian abbot of our own times: What was carried out was not a reform but a deformation of the traditional liturgy that transformed it into a hybrid that came to be called the Cistercian-Roman Rite, the modern Cistercian rite, or the reformed rite.”[19] It would, however, be unjust to the memory of Claude Vaussin to lay the responsibility for the actual hybrid liturgy at his door, and it was thanks to him that the Order has preserved a vestige of the traditional rite.[20]

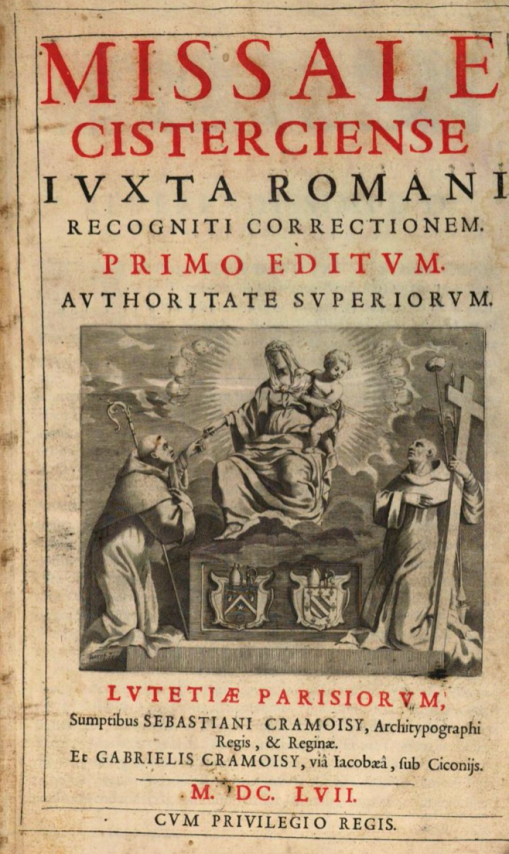

The liturgical commission presented its conclusions to the general chapter of 1654,[21] and two years later (1656) the breviary was published: Breviarium cisterciense juxta Romanum. The monitum at the beginning of the book expresses the intentions of Dom Claude to maintain the Benedictine ordo of the Office and to safeguard the groundwork of the ancient Cistercian rite.[22] The missal appeared in the following year (1657): Missale cisterciense juxta novissimam Romani recognitum correctionem.[23] The ordo Missae Romanus was introduced, together with the ritus celebrandi of the Roman missal, the general rubrics (verbatim) and a new classification of feasts, while retaining the old vocabulary. A certain amount of confusion and difficulty was caused, as the ritus celebrandi was not always in agreement with the Cistercian consuetudines, and it became evident that a ceremonial of ritual was a vital necessity.

Such was the Vaussin compromise, but, notwithstanding its tacit approval by Rome, it was in jeopardy at the hands of those whom nothing short of the actual Pian rite would satisfy. The Congregations of Lombardy and of the Feuillants bitterly attacked the new books. Hilarion Rancati, abbot of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (Rome) and John Bona, abbot of S. Bernardo (Rome), had prepared “reformed” books for the use of the Order, and it was particularly galling that they should have been forestalled by the abbot of Cîteaux. Rancati, who was a consultor to the Congregation of Rites, demanded an examination of the breviary of 1656 on the ground that its compilers had acted without the approval of the Holy See. In January 1660 the Congregation submitted the breviary to Cardinal Franciotto, but it was agreed not to give a decision till the procurator of the abbot Cîteaux had arrived. Notwithstanding this, however, a new decree suspended the breviary of Vaussin (24 July), and directed Cardinals Franciotto and d’Este to produce another edition. Rancati had won the first round, and there was the possibility that his breviary would be approved for the Order. John Bona, who wanted neither the breviary of Vaussin nor that of Rancati, seeing that there was little hope of his own book being accepted, thereupon proposed the adoption of the monastic breviary of Paul V.

A decree was obtained from the Congregation of Rites to the effect that, while the use of the ancient breviary was forbidden, the various 17th-century reforms were also ultra vires. The Order, says the decree, was committed to the monastic breviary, with the addition of the offices of our Lady and of the dead. The procurator of the abbot of Cîteaux attempted to intervene, but a second decree, issues on 23 July of the same year (1661), merely repeated the injunction of 2 July. A year’s grace was permitted before the monastic breviary became obligatory, but the Feuillants and the Congregation of Lombardy and Tuscany adopted it immediately, and also the missal of Pius V; while the rest of the Order continued with the books of Claude Vaussin. The abbot of Cîteaux was profoundly attached to the Cistercian rite, and he applied through his procurator for an extension of the reprieve. On 3 June 1662 the Congregation of Rites directed that he could keep his liturgical books usque ad Capitulum generale in quo possit deliberari super provisione novorum codicum. The Pope disapproved of this concession,[24] but the abbot of Cîteaux was determined to continue the struggle and, in order to facilitate the retention of the books, he resolved to make the liturgical reform part of the general reform of the Order.

A brief of January 1662 declared the reforming activities of Cardinal de la Rouchefoucauld and the other commissaries who had been authorized by the Holy See to be null and void, and an assembly for the general reform of Cîteaux was summoned to the supreme tribunal of Rome. The judges were to be no longer members of the Congregation of Rites, but a commission of cardinals. The supplica presented by the Cistercian procurator was astutely worded, with the question of the liturgical books made part of the general reform. The ruse succeeded, and the Pope (Alexander VII) ordered a supersederi to the immediate execution of the decree prescribing the adoption of the breviary of Paul V and the missal of Pius V.

On 19 April 1666 the famous constitution for the reform of the Cistercian Order, In Suprema, was issued. One of the articles gave pontifical approbation to the ensemble of the Cistercian rite: prout hactenus consuevit Ecclesia cisterciensis. The liturgical reforms of Claude Vaussin were saved. “The Order of Cîteaux, thanks to the clever diplomacy of Claude Vaussin, preserved its own rite, if not in integrity, at least in a measure which still gave a richness to the Order.”[25]

The brief, among other things, directed:

- All should follow strictly the form established by St Benedict, which has always been observed in the Cistercian Order.

- Only those Roman usages should be adopted which the Order of Cîteaux has been accustomed to use.

- The Order is to practice the uniformity which is required by the Charter of Charity and the constitutions of Blessed Eugenius III and St Pius V, in conformity with the traditions of Cîteaux, Mother of all the churches of the Order.[26]

Papal approbation was accorded to the reformed books of Claude Vaussin because they contained the liturgical customs in use at Cîteaux: it was not the Cistercian rite as found in any particular book.[27]

In Suprema heralded an era of stabilization after a long period of confusion, agitation, and struggle. There was, however, a certain liturgical codification still to be achieved, as the Order had retained its traditional liber usuum or consuetudines. The general chapter of 1667 deliberated on the practical application of the points made in the decree of reform, and decided not to make any further alterations in the breviary, which was to be followed by all professed monks of the Order.[28] The brief Ecclesiae catholicae of Clement IX (26 January 1669) renewed the approval of Alexander VII (In Suprema), and confirmed the previous decisions of the general chapter.[29] A century later, we find Clement XIII, who wished to encourage a reform, of which the abbey of Salem in Swabia was the centre, repeating word for word the brief of Alexander VII.[30] Again in 1871 (7 February), Pius IX, in the brief Quae a sanctissimis, used almost identical terms.

We have seen how much of the traditional Cistercian rite was sacrificed on the altar of “novelty”, but as Fr Colomban Bock says, “When one sees with what levity a Cistercian of the stamp of Cardinal Bona has encouraged the suppression of the Cistercian rite and clung without regret to this line of action, one is filled with a profound gratitude for the work realized by Claude Vaussin, who was and will ever remain one of the shining glories of the Order of Cîteaux.”[31]

[…]

As we have seen, the reformed books of Claude Vaussin were adopted by the houses more or less directly under the jurisdiction of the abbot of Cîteaux, while a different breviary was used by the French Feuillants, and the Roman missal and monastic breviary of Paul V by the Feuillants of Italy. Some of the houses of the Common Observance in Italy have also the monastic breviary, and when their chapter wished to adopt the reformed Cistercian book, the Congregation of Rites (31 May 1907) refused to permit a change.

One Cistercian Congregation, the Congregation of Regular Observance of Castile,[32] maintained the traditional rite for both Mass and Office until the 19th century, although love of “novelty” had introduced certain Roman features. […] A missal had been issued for the Congregation in 1589 (Missale Sacri Ordinis Cisterciensis), 1606, and again in 1762. In the last-named edition, printed in Antwerp, the following note occurs under the paragraph Ritus servandus:

Since this our Order has always had a special book of ceremonies, vulgarly called Libro de los Usos, which sets out with the greatest clarity the general and particular rubrics necessary to the celebration of the mass, we have therefore deemed that nothing should be inserted here.[33]

An edition of the old missal appeared for the Congregation of Portugal in 1738.[34]

The religious orders were suppressed in Portugal in 1834, and in Spain the following year. Many of the dispossessed religious took refuge in France, and it said that the last Cistercian monk of the Spanish congregation, a monk of Valdigna in the diocese of Valencia, died in 1877 or 1878, and that the old mass died with him, although the Office lingered on in some of the Bernardite convents. This has been the commonly accepted opinion, but a recent history of the abbey of Veruela says that a former monk of that house by the name of Antonio José Viñes returned on a visit in 1877, after its occupation by the Jesuits, and that he was present also at the ceremony of the crowning of Our Lady of Veruela in 1881.[35] A former abbot of Sainte Marie du Désert, speaking of the retention of the old Office by the Spanish convents, says: “The traditional Cistercian rite still, therefore, exists on a corner of the earth, like a spark covered with ash. Will God allow it to be relit?”[36]

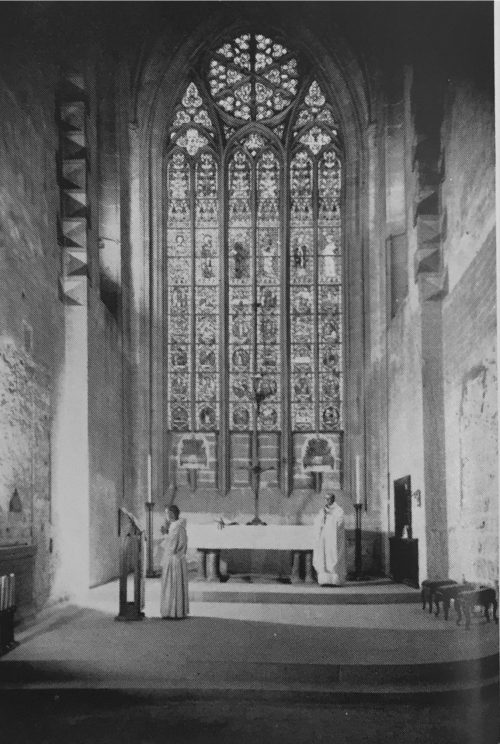

God has heard his prayer, and the “spark” has become a steady flame. In the abbey of Boquen in the diocese of St. Brieuc, a house of the Common Observance which was restored in 1936, the Divine Office is recited according to the old Spanish breviary,[37] and the Mass is celebrated with the rite of 1608, collated with that of the 12th century.[38] An indult was received from Rome for the restoration of the traditional rite, although it may be argued that this was unnecessary as it had never been formally suppressed. The monastery of Hauterive in Switzerland, which was restored to the Order in 1938, has been permitted to use the old rite at the conventual Mass on Sundays ad experimentum. Poblet, also, in Catalonia, recovered by the White monks in 1940, is working towards a revival of traditional usages.

NOTES.

[1] Dioceses with their own venerable use could only switch to the Roman with the unanimous acquiescence of the bishop and all the chapter canons).

[2] André Malet, La Liturgie cistercienne (Westmalle, 1921), part III, art. III, p. 46.

[3] Ap. Louis Meschet, Privilèges de l’Ordre de Cisteaux (Paris, 1713), p. 167.

[4] Jure inde ac merito inclyta cisterciensis familia… suos retinuit liturgicos libros. Pii IX P. M. Acta, vol. VI, part I (Rome, 1873), p. 383.

[5] Certain esprits, amateurs de nouveautés, et sans estime pour la tradition, poussaient à l’abandon des formules liturgiques cisterciennes pour adopter la nouvelle réforme romaine. André Malet, op. cit., part 2, art. IV, p. 18.

[6] Schneider, L’Ancienne Messe Cistercienne, part 2, XVIII, p. 242.

[7] Cap. Gen. 1601, VI; Canivez, Stat., t. VII, p. 204.

[8] Abbatibus et monachis Poloniae et Prussiae in itinere et extra monasteria Ordinis constitutis, more romano missa celebrare conceditur. Cap. Gen. 1605, LXXXIV; Canivez, op. cit., t. VII, p. 263.

[10] Concessio nonnullis abbatibus et monachis praecedenti Capitulo facta ut extra Ordinis monasteria constituti romano ritu celebrare possint revocatur ne per eam solvatur Ordinis uniformitas.

[11] The rubrics for the Mass were in the liber usuum, and only general rubrics as to the nature of the Masses were inserted at the end of the missal.

[12] An ordo missae was produced by Wolfgang Aprilis, a monk of Hohenfurt, in 1576: Canon minor et major secundum usum Sacri Ordinis Cisterciensis.

[13] Missale ad usum S. O. Crist. juxta decreta Capituli generalis dicta Ordinis, Romano conformius redditum primo accentibus ornatum et auctum. Paris, chez Sebastian Cramoisy, 1617.

[14] Ordinatur ut deinceps missa tam conventualis quam privata ritu et ceremoniis romanis ab omnibus tam abbatibus quam monachis, absque ulla exceptione celebretur, quare psalmus Judica me Deus, Confiteor, et caetera alia dicentur, prout in ipso ritu romano descripta sunt. Retinebitur tamen in reliqua missale et officium Ordinis, excepto quod psalmus Laetatus sum et annexae collectae omittentur. Cap. Gen. 1618, XIV; Canivez, Stat., t. VII, pp. 332-333.

[15] Louis Lekai, The White Monks, XIV, pp. 182-183.

[16] Cap. Gen. 1623, XLIV; ibid., t. VII, p. 353.

[17] The most recent edition was printed at Westmalle in 1925.

[18] Ad reparandum in officio divino sacri Ordinis uniformitate statuit Capitulum generale ut libri Ordinis corrigantur et imprimantur, ad quod correctionis et impressionis munus deputat…dans eis plenariam potestatem addendi, tollendi et mutandi quae additione, sublatione et mutatione digna judicaverint. Cap. Gen. 1651, XXII; Canivez, op. cit., t. VII, p. 405.

[19] Ce n’était pas une réforme que l’on opérait, mais une déformation de la liturgie traditionelle pour la tranformer en un mélange qui a pris le nom de Rit Cistercien-Romain, rit Cistercien moderne, rit réformé. André Malet, op. Cit., part II, art. IV, p. 20

[20] Ibid., p. 21.

[21] Cap. Gen. 1654, VII; Canivez, Stat., t. VII, p. 418.

[22] Some members of the Order were advocating the adoption of the Roman breviary tout simple.

[23] The missal was reprinted in 1669.

[24] Decree, 8 July 1662

[25] Malet, op. cit., p. 22.

[26] In Suprema, cap. IV, circa cap. VIII usque ad cap. XIX Reg. Bened., De forma officii; Séjalon, Nomast. Cist., p. 596; Canivez, op. cit., t. VII, p. 429.

[27] Trilhe, Mémoires pour le cérémonial cistercien, p. 21.

[28] Cap. Gen. 1667, XXIII; Canivez, op. cit., t. VII, p. 447.

[29] Nomast. Cist, p. 608.

[30] Brief Impositi nobis, 8 August 1760.

[31] La Réforme du Droit Liturgique dans l’Οrdre de Cîteaux, Collect. Ord. Cist. Ref. (January 1952), p. 23.

[32] In 1425 a bull of Martin V excluded the Congregation from the jurisdiction of the general chapter at Cîteaux.

[33] Cum in nostro hoc Ordine semper fuerit peculiaris liber ceremoniarum qui vulgo Usus vocari solet, in quo Rubricas generales et particulares necessariae ad missarum celebrationem maxima cum claritate habentur, idcirco nihil hic inserendum duximus.

[34] Missale Cisterciense ad usum sacrae Congregationis Divi Bernardi in Lusitania et Algarbiorum Regnis, Antwerpiae et Architypographia Plantiniana.

[35] Pedro Blanco Trias, El Real Monasterio de Santa María de Veruela, XI, pp. 284, 290. Palma de Mallorca, 1949.

[36] Le rit Cistercien traditionnel est donc encore sur un coin de terre comme une étincelle couverte de cendre. Dieu permettra-t-il qu’il soit rallumé ? André Malet, op. cit., part II, art. IV, pp. 25-26. Missals may still be seen in some of the convents, says the abbot, but here are no priests to use them.

[37] Breviarium operis Dei ad usum sacri almi Ordinis Cisterciensis per Hispaniam, Madrid, 1826.

[38] Dijon, Bibl. municip., MS. 114 (82). Written between 1179 and 1191.