Today we present a chapter from Prosper Guéranger’s Institutions Liturgiques, wherein he attacks the artistic decadence of the Gallican Church, contrasting it with the sobriety and universality of the Roman rite.

Introduction

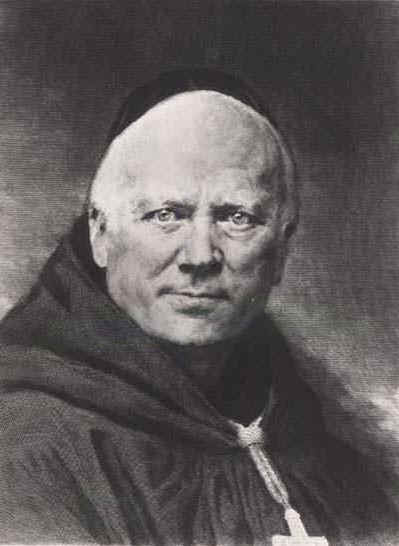

In his recent book Vatican I: The Council and the Making of the Ultramontane Church, John O’Malley pointed out Prosper Guéranger’s (1805 – 1875) key role in the great ecclesiastical controversy of the 19th century.

In the chaos of post-Napoleonic France, while figures such as De Maistre and Lamennais argued strenuously that the Church had to submit to a strong Roman authority in order to confront the centralized power of the rising secular nation states, Guéranger saw that “liturgical unity was essential to the success of the Church’s renewal.”

Unity under the one Roman Rite, which to his mind had always preserved itself serenely from error in all its parts, would guarantee the salutary spiritual submission to Roman authority that the liturgical diversity of the Gallican Church had always prevented.

Therefore, as Peter Raedts argues:

“What Guéranger contributed to Ultramonantism was not his passion for the pope, nor his reactionary political ideas, but his unique insight into the possibilities of the liturgy as a way of visualizing the unity of the Church and the authority of the pope everywhere in the Catholic world.”[1]

The Institutions Liturgiques (pub. 1841 – 1851) were a major step in this direction. Written after his move to Solesmes, “the Institutions launched Guéranger’s campaign to install [the Roman Rite] in the churches of France and then in the other churches throughout the Catholic world”[2] The work treats the history of the Mass in the West, with special focus on France in the modern period.

Raedts argues that “the thrust of the book is more political than historical; Guéranger did not so much want to describe the past as to change the present.”[3] He aimed to show that, in liturgy as in doctrine, Rome had always been a bulwark against heretical influence. Aware of this polemical purpose, the modern reader has to read cautiously, as Gregory DiPippo argues:

“Guéranger was a 19th-century romantic, with all that that entails. It has been noted more than once that he sometimes let his zeal get the better of his judgment; what he writes here should not be taken as the final word on the condition of the music in the Neo-Gallican period, of which he knew only the rump end. He was born in 1805, when most of the chapter system was already completely destroyed, so would not have heard most of what he is describing in actual liturgical use. It should also be remembered that the ‘pure’ Gregorian chant of Rome was also in pretty awful shape in his time, with everybody using the reduced music of the old Medicean edition.”

For a reader who keeps this caveat in mind, the Institutions remains a useful work of erudition and scholarship. It is of timely importance for understanding the development of the “ultramontane Church,” and a landmark of the Romantic phase of the Liturgical Movement.

Would that some generous soul would undertake the immense labor of translating the whole work!

(excerpt from Ch. XX of Vol. II of the Institutions Liturgiques, 1st edition, Mans, 1861, pp. 428-449)

“The General Character of the Liturgical Innovation in Relation to Poetry, Chant, and Aesthetics in General”

Let us rather say that these men, who remade the liturgy according to their own ideas, although perhaps unaware of the evil they foisted upon us, have contributed as they could to the total extinction of Catholic poetry in France on account of their utter ignorance of good taste. They expunged from the liturgy the ancient chants of Christendom, and put in their place the pretentious patchwork of their scriptural antiphons and responsories. We will not reflect now upon the effects of their liturgical innovations on literature, since we shall discuss the language and style of the liturgy in another part of this work. Let us then go over the effects of the liturgical revolution on chant.

[The Revolution in Chant]

This is one of the deepest injuries we must report. One could consider the question solely on an aesthetic level, or on the much more serious one of Catholic sentiment. We shall first denounce the barbarous anti-liturgists of the 18th century, who bereaved our fatherland of one of the most admirable glories of Christendom. We have seen elsewhere how the last remnants of ancient music were set down by the Roman pontiffs, and especially St. Gregory, in the two repertoires called the Roman Antiphonal and the Roman Responsorial. This collection, made up of many thousands of musical compositions, most of them of solid and melodious character, had accompanied all the Christian centuries in the expression of their joys and their sorrows. From this source Palestrina and the other great Catholic artists took their inspirations. For posterity, it was a sublime spectacle to see that the genius for preservation innate to the Catholic Church was the means by which the famous music of the Greeks and the harmonies of the days of yore reached—in a purified, corrected, and Christianized form—barbarous Western ears, which it proceeded to soften and civilize.

In the new [Neo-Gallican] breviaries and missals, almost all these ancient compositions were replaced by completely new ones. It necessarily led to the material suppression of all the ancient melodies and hence to the loss of many thousands of old pieces, a great number of which were remarkable for their nobility and originality. Lo! An act of vandalism if there ever was one, and one for which the 18th century, with its frenzy for destruction, has yet to be rebuked. And what excuse could they possibly give to justify such monstrous destruction? On the one hand, liturgical manufacturers such as Frédéric-Maurice Foinard[4] said that nothing would be easier than transporting the motifs of the ancient responsories and antiphons onto new texts,[5] and we have seen how they got together to prepare the material for the composers. On the other hand, there were forgers of plainchant who actually thought that if they composed new chants without materially departing from the character of the eight Gregorian modes, all would be well. As if it were no great loss to abandon an immense number of compositions from the 5th and 6th centuries, veritable vestiges of ancient tunes! As if inspiration were assured by adhering perfectly to the rules of Gregorian tonality! For, let us remember, if they were going to interfere they should have been able to do a better job than the Romans.

It was certainly a pitiful sight to see our cathedrals forget, one by one, the venerable canticles whose beauty had so ravished Charlemagne’s ear that he, acting in concert with the Roman pontiffs, made it one of the most powerful tools for civilizing his vast Empire; and then to hear them resound with the great noise of a torrent of new compositions bereft of melody, bereft of originality, as prosaic for the most part as the words they enshrouded. Admittedly, they did set a certain number of the new texts to old Gregorian melodies, and oftentimes even with happy results. Some of the new compositions, too, were quite inspired. However, the bulk of them were frightfully crude, and the best proof thereof is that it was impossible to learn these new chants by heart, whereas the people’s memory was a living repository of the vast majority of the Roman chants.[6] When performing these boring new melodies, they could not have enough serpents, double basses, and counterpoint, under the noise of which the chant almost entirely disappeared. The Gregorian tunes, on the other hand, being so lively, vibrant, and often syllabic, were declaimed with sentiment, even when singing in unison, so that they produced great effects upon the souls of the faithful, impressing upon them the thoughts their texts expressed.

The suppression of the Gregorian books was not only a loss for art, but a calamity for popular faith. A single consideration will allow us to understand this point and at the same time expose the culpability of those who dared to do such a thing. The divine offices are of no use to the people unless they are interesting to them. If the people sing along with the priests, one can justly say that they are assisting at the divine service with pleasure. But if the people are used to sing during the offices, and all of a sudden are forced to keep silence and allow the voice of the priest alone to be heard, one can also justly say that religion has thereby lost a large part of its attraction for the people. Yet this is precisely what has happened in the greater part of France! And so the people have, little by little, deserted the churches, which became mute for them on the day they could no longer join their voices to that of the priests. This is so true that if in those churches that resound with modern chants the people ever attempt to join their voices with those of the clergy, it is when they perform (usually in a disfigured way) some of the ancient Roman compositions, such as the Victimae Paschali, Lauda Sion, Dies irae, certain responsories or antiphons of the Blessed Sacrament, etc. When, however, it comes to the new responsories, introits, offertories, etc., the people listen without paying attention, or rather they put up with them passively, without attaching any idea or sentiment whatever to them. But go to one of those last parishes in Brittany whose choirs still sing Roman chant, and you shall hear the entire people sing from the beginning of the offices to their end.[7] They know by heart the easy melodies of the Gradual and the Antiphonal. That is how they expressed their great joys on Sunday, and during the week, one can often hear them repeating them as they work. Surely, it would be an extremely serious thing to tear this music away from them, for that would vastly diminish the interest they take in the Church’s offices.

If, after these saddening reflections, we were to move on to the history of the Revolution as it affected the singing in our churches in the 18th century, we would say lamentable things. Think of the frightful task imposed upon the composers of plainchant from the moment when the brains of those learned men hatched their new breviaries and missals, and when the printers, burdened like never before with books of this genre, finally brought them to light. Before they could launch these masterpieces, they had to take the necessary measures so that the entire corpus of new pieces could be chanted in the choirs of cathedral, collegiate, and parish churches. Thousands of pieces had to be improvised. Now recall the great Gregorian Antiphonal. A repository of ancient music, a body of melodies popular, grave, and religious, a work that harkens back at least to St. Celestine, gathered and corrected by St. Gregory, then by Leo II; then enriched again every century; presenting a marvelous variety of chants, from the severe motifs of Greece to the tender and moving strains of the Middle Ages. What did the 18th century have to offer in replacement? First, we cannot repeat enough that this meant an immense loss of so many remarkable musical pieces, popular and often of historic value, but let us go further. How many hundreds of musicians would be employed for this great task? Where, in the age of Louis XV, would one find men able to replace St. Gregory? Would 50 years be enough time to complete such a work? Alas! Any hypothesizing is pointless. Within two or three years everything was ready, composed, printed, published, and chanted with the noise of serpents, double basses, and loud voices.[8] Do you want to know how many dioceses found the men needed to cover the antiphons in question with great big musical notes, how they went about inviolati inveniri in pace? [9] They made an appeal to men of good will. As we have seen, those in charge of the whole operation were bereft of any instinct for art and poetry, and so they were hardly difficult or demanding when it came to the melodies. A learned 18th-century writer on plainchant, Léonard Poisson, Curé of Marsangis, had this to say in his Traité historique et pratique du Plain-chant appelé Grégorien:

Of all the churches that adopted new breviaries, some, it is true, made greater haste to compose the chants than others. All of them, however, wanted to see the completion of this task at any cost, and sought all sorts of ways to satisfy their eagerness to use the new breviaries. Hence the rabble of people who put themselves forward to compose the chants. Everyone pretended and thought himself capable to composing them. Even some mere schoolmasters did not shy away from signing up. Because their profession involves using chant and ordinarily they know how to chant better than others, they too threw themselves into the work. Isn’t it astounding that musical pieces by such people were adopted by men who doubtlessly were not as ignorant as they? For, although they knew how to sing well, these schoolmasters were nonetheless ignorant of Latin, which is the language of the church. And so, anyone can see how many blunders such a handicap necessary entailed.

Thus for the composition of the new chants, they chose those they thought most capable, and placed the entire execution of this great work on their shoulders. Such an enormous enterprise required a proportionate amount of time, and they were rushed. In response to the urging of those who had chosen them, they were hasty in their work. Their pieces were sung almost immediately after the compositions left their hands. Everything was received without careful examination, or with a very superficial examination, and this only after printing, without having tried them out. Only after they had been authorized for public use were their defects perceived, but too late, and after there was no longer any time to fix them.

Then they saw with regret, either that they were were mistaken in their choice of composers, or they had pressed them to work too quickly. It is not possible to ignore the innumerable and often gross shortcomings of these compositions, which of course ought to have been pleasing at least for their novelty, but which did not even have this minimal advantage.

Who indeed could bear faults as clumsy and revolting as those which for the most part fill these works? I mean the errors in metric quantity, especially in the music of the hymns; the phrases mixed up by the tenor and flow of the music, which should have been marked out as they are by the natural sense of the text; other phrases maladroitly split up; others maladroitly left hanging; chants utterly opposed to the spirit of the words: grave, when the words called for a light melody; a rising melody, when it should have been falling; and so many other irregularities, almost all caused by a lack of attention to the text.

Who would not be disgusted to hear these same old chants so frequently—so many responsories, graduals, and alleluias—, which are truly beautiful in themselves, but were imitated too often, almost always disfigured, and generally at the expense of the sense expressed by the text and at the expense of the flow and energy of the primitive chants?

What more can be said about the exaggerated and neglected expressions; forced tones; lack of good judgement in the choice of modes, without regard for the text; and the childish affectation of arranging them by number seriatim,[10] i.e. by putting the first antiphon and first responsory of an Office in the first mode, the second antiphon and second responsory in the second mode, and so on, as if any mode were appropriate for any words and any sentiment?[11]

This is the judgement of the liturgical innovations with respect to chant by a man who was adroit in composition, nourished by the best traditions, and otherwise full of enthusiasm for the texts of the new breviaries. He is therefore an irrefutable witness. We will only add one more word about the new chants, viz. that although it was inexcusable that the fabrication of new chants in certain dioceses was left up to the mercy of the multitude, it was no less deplorable to impose the colossal mission of filling up three enormous volumes in-folio with musical notes upon a single man. Yet this is exactly what happened with the new Parisian breviary. The Herculean task was imposed upon Fr. Jean Lebeuf, a canon and sub-cantor of the Cathedral of Auxerre. He was a learned and industrious man, profound in his theoretical discussions of ecclesiastical chant and well-versed in the antiquities of this genre. That was something, but even if his spark of genius had been greater still, it could not but be snuffed out soon enough under the thousands of pieces he had to put to music, despite their multitude and the strange circumstances of their manufacture. For all that, he approached this task in good faith and, since he appreciated the ancient chants, he strove to introduce its motifs into many of the new pieces. “I never had the intention,” he said, “of providing anything new. I decided to centonize, as St. Gregory had done. I have already said that to centonize means to draw from everywhere and make a selection out of all one has gathered. All those who worked before me in similar tasks either made a compilation or at least tried pastiche. I intended to do sometimes the former and sometimes the latter.

“By and large the Antiphonal of Paris follows the lines of the previous antiphonal, which which I occupied myself in 1703, 1704, and thereafter. But since Paris is inhabited by clerics from the entire kingdom, many noticed that that there sometimes was too much levity or aridity in Archbishop de Harlay’s antiphonal. And so I have used the melodies of 9th-, 10th-, and 11th-century French symphoniastes[12] more widely or more frequently, especially for the responsories.[13]

These intentions were praiseworthy and one ought to do justice to them, but the results failed to live up to the intentions. Besides a small number of compositions, part of which had been written by Fr. Claude Chastelain for the previous version of the Parisian books, one must admit that the Parisian Gradual and Antiphonal are entirely devoid of interest to the people; that its music is not of the sort easily learned by heart; and that it is difficult even to perceive an overall melody in the new responsories, introits, offertories, etc. The imitations, even if done note by note (which is at any rate impossible), are usually unable to reproduce the effect of the original compositions, because these latter have no rhythm and hence owe their character entirely to the sentiments expressed in the words, to the words themselves, to the sound of their vowels. Moreover, the syllables are not measured, so it is almost impossible to find two pieces that perfectly match in syllabic number. One must, therefore, eliminate or add notes, and so sacrifice the entire expression of the piece.[14]

We have spoken elsewhere of the Introit for All Saints, Accessistis, which Chastelain based on the Roman Gaudeamus with such felicitous results. Lebeuf rarely matched this standard in his imitations, and with respect to the compositions of his own invention, they are almost always impoverished, cold, and bereft of melody. The numerous chants he had to compose for hymns are also sad and monotonous, showing that he had none of the creativity Chastelain displayed in the music he composed for the Stupete gentes. Lastly, Lebeuf was unable to liberate Parisian chant from those horrible quarter notes called périélèses, which ultimately disfigure the rare beautiful melodies among his compositions. It is impossible to recall without indignation that the Alleluia verse Veni, sancte Spiritus, a tender and sweet melody miraculously retained in Archbishop Ventimille’s Missal,[15] is torn up seven times by these quarter notes. One is tempted to surmise that Lebeuf feared that this piece, if allowed to retain its original melody, would make too manifest a contrast with the pile of new and insignificant morceaux that surround it.

Lebeuf’s fecundity gave him a reputation. In 1749, when he was over 60 years old, he accepted the offer to compose the chant for the new liturgy of the diocese of Mans. In a period of three years, he succeeded in giving musical notes to the three enormous volumes that make up this liturgy. And so this composer furnished the liturgical innovation with a contingent of three volumes in-folio of plainchant! It was nevertheless evident that Lebeuf’s last work was of even lower quality than the first. Weariness had finally caught up with him. But one doesn’t hear that he ever felt any remorse for the active part he played in the vandalism of his century.

[Modern Chant Styles]

Enough talk of the new chant-books that replaced the Gregorian melodies. We will only add a word on the subject of the all-too-famous plain-chant figuré, which we have proposed elsewhere to our readers’ animadversion, and which was again in vogue in this time of universal destruction of the ancient chant traditions. An immense number of compositions of this sort blossomed, first in the hundreds of new proses [i.e. sequences], mostly bland when not mere ditties in the style of the Régence.[16] This era also produced the insipid collection known under the title of La Feillée, which is still regarded as the archetype of musical beauty in many of our provincial seminaries. We will limit ourselves to insert here the judgment of Jean-Jacques Rousseau on this ignoble and bastardly form of music whose unfortunate charm has so unhappily contributed to distract French singers from the sad loss of the Gregorian repertoire:

“The modes of plainchant, as they have been transmitted to us in the ancient ecclesiastic chant, preserve therein a beauty of character and a variety of affections very sensible to an impartial connoisseur, and which have preserved some judgement of the ear for the melodious systems established on principles different from ours: but we may well say that there is nothing more ridiculous and more flat than these plainchants suited to our modern music, embellished with the ornaments of our melody, and modulated on the chords of our modes; as if our harmonic system could at any time be united to that of the ancient modes, which is established on principles exactly opposite. We ought to thank the bishops, prevosts, and choristers who have opposed this barbarous mixture, and use our utmost endeavours for the progress and perfection of an art which is very far from the point at which it has been placed, that these valuable remains of antiquity may be faithfully transmitted to those who have sufficient talents and authority to enrich the modern system by the addition of them.”[17]

[The Other Liturgical Arts: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Vestments]

We have said elsewhere that all arts are tributaries of the liturgy, and again and again lend themselves to its sublime pomps. We have just seen what 18th-century innovation made of ecclesiastical chant; the other arts followed the liturgy in its degradation. We have already pointed to decadence in the latter half of the 17th century. It became more profound and more humiliating when the churches of France in their greater number abjured the ancient traditions of the liturgy to create new forms to the taste of the age. Religious painting, which in the 17th century descended from Eustache Le Sueur to Nicolas Poussin and Pierre Mignard, took shelter in the workshops of François Boucher and his school. Thus the same brushes that decorated the boudoir of Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry in the time of the little epigrams of the Abbé de Bernis[18] degraded the severe majesty and suave mysticism of Catholic artistic subjects with affected grimaces and effeminate poses.

Sculpture, no less impoverished and just as materialized, had nothing to offer in representing Our Lady than the vacuous posing of Edmé Bouchardon’s Virgin, or the fat and burly bearing Charles-Antoine Bridan gave the Queen of Angels even in her Assumption into heaven.

But how could such works (and out of modesty we have only cited the least boorish production of this age), how could such works be accepted for as church adornments by the grave characters who delighted in the new breviaries, whence all the carnal license of the Roman Breviary had been severely expunged? Here we must admire the judgements of God. It is written that whosoever is puffed up in spirit falls by the flesh; this is a universal law. Yet, since the partisans of innovation were unaware of the full extent of their fault on account of their utter impotence in matters of poetry, God allowed the sense of the beautiful to be extinguished in them. By leaving them to the mercy of the degraded artists of the age of Louis XV, he did not allow their consciences to sense the degree of profanation they allowed them to carry out. They gave themselves up so confidently to these artists of the flesh that the Parisian Breviary of 1736 itself shows on its frontispiece some repulsive courtesans bedecked in the attributes of Religion. They even found a way to introduce some variety into each of the four volumes, so as to show the richness of the brutish brush of the age. The 1738 Parisian Missal also offers on its frontispiece a virago plopped down upon clouds and likewise tasked with representing Religion. The collection of these sundry engravings will someday be the precious monument of the horrible familiarity with which artists of that time treated religious subjects, and proof of the clergy’s indifference to anything related to art, even in connection with divine worship. But we must still mention the last effort at scandal: the frontispiece of the 1782 Missal of Chartres, in which the Immaculate Virgin, the glory of this town and its ineffable cathedral, is outraged with an immodesty that forbids all description.

This indifference to form, a few of the effects of which we have just pointed out, also led to the suppression of the innumerable rich engravings around solemn feasts which had thitherto adorned the new missals and breviaries. This custom had persisted until the 18th century as a souvenir of the rich miniatures that gave life to the ancient missals and antiphonals. The new Parisian Missal of 1738 still had images for feasts, but done anew by artists of the time. In the second half of the 18th century, the missals of the rest of France contented themselves with an engraved frontispiece at best, and most limited themselves to a Crucifix, which they dared not remove from the first page of the Canon. Happy were those that did not place, as did the Parisian Missal of 1738, Jesus Christ’s arms above his head to prevent him from embracing all men. That sort of crucifix was a symbol dear to the Jansenists, and we know how much influence this party had over divine worship in France at this time.

One can well imagine the fate suffered by architecture, the most divine of the liturgical arts, in this unhappy age. It waned even more than it had at the end of the 17th century. Domes like that of the chapel of Hôtel des Invalides[19] were no longer built. (Italian-style churches, with their luxurious paintings and marbles, although out of place in our cold and foggy climate, are always, whatever one might say, Christian churches.) The Church of Saint-Sulpice,[20] so bare and stripped of soul and mystery, was soon found too mystical. Louis XV lay the cornerstone of two new churches. One, Sainte-Geneviève, was to have a dome, but on the condition of having a portico in front of its doors inspired by Agrippa’s Pantheon, so that passers-by would think it was a pagan temple. The other, which was to be open presently, looked as if it were prepared for Minerva; Louis XV intended to dedicate it to St. Mary Magdalene.[21] Admittedly, the original plan was entirely different to the one that was adopted in our day. What need is there to talk of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule, built a bit later,[22] modeled perfectly on an ancient temple, and so many other churches that have neither pagan or Christian appearance! To such a degree were sacred traditions forgotten that no one raised his voice in protest and no complaints were made. To that degree had religion, as understood by the French, departed from form! Such was the depth of the break from the Ages of Faith!

This was also the source of the degradation of priestly vestments, especially of the surplice, whose sleeves, which around the middle of the 17th century had already been split and let to fall behind, were in the 18th century stretched out and entirely separated from the body of the surplice itself. They took the name of ailes [wings], waiting for the 19th century to amuse itself by pleating them in the ridiculous and uncomfortable fashion of our days.

When it comes to the choir biretta, it was, at the beginning of the reign of Louis XIII, the same in France as it was in the other churches of the Catholic world. By the end of the 17th century, the projection of its upper part had been eliminated, and the biretta itself lengthened it by a third. In the 18th century, this upper part was made pointed and the body of the biretta was lengthened further still, thus leading to the ridiculous and annoying headpiece of our day, which looks like a candle snuffer and thus compromises the gravity of priestly functions, and gratuitously furnishes freethinkers with an occasion to declaim against the bad taste of the Catholic Church.

The rationalist spirit of which Dom Claude de Vert, the voice of his century, was the apostle, contributed to the clergy’s neglect of religious aesthetics. To the eyes of a spiritualist religion, only one thing can elevate form, and that is mysticism. But since this rationalism deprived the ceremonies of their proper objective—viz. to sanctify visible nature by making it serve the expression of the invisible world—it is easy to understand how the clergy, already deprived of the poetic elements of the ancient liturgy, could reach such an indifference to art with respect to worship. This is the opposite of what happened in the Middle Ages, when Catholicism spiritualized material nature, divinizing science through its contact with theology, and sanctifying the government of society by the upshot of Christ’s Kingdom.

[Contemporary Evaluations of the Neo-Gallican Rites]

We could continue to protract these reflections, but we will come back to them in due time. Now we will bring together some contemporary judgements about the new French liturgies, and show that illustrious prelates—Jean-Joseph Languet, archbishop of Sens; Charles de Saint-Albin, archbishop of Cambrai; François-Xavier de Belsunce, bishop of Marseille; Jean-Félix-Henri de Fumel, bishop of Lodève; etc.—were not the only ones in the 18th century to defend liturgical tradition and judge the work of the reformers with severity.

The first judgement we shall produce is—would you believe it?—Foinard himself; he is all the less suspect. In his Projet d’un nouveau Bréviaire, while explaining the new liturgies tried out before 1720, condemns them with these observations, which are just as applicable to the breviaries put out thereafter:

“It does not seem that unction is the basis of the new breviaries. They have, it is true, labored much for the mind, but it does not seem that they have labored as much for the heart.”[23] Later on, he adds these remarkable words: “Could it not be said that most of the antiphons in the new breviaries were only made to be seen by curious eyes outside of the Office?”[24]

Let us now harken to Fr. Urbain Robinet, author of the breviaries of Rouen, Mans, Carcassone, and Cahors. Here is a valuable admission: “Those who composed the Roman Breviary had a better taste for prayer and the words appropriate to it than we do today.”[25]

The testimony that follows that of Robinet in chronological order is that of Pierre Collet in his Traité de l’Office divin, first published in 1763. Speaking about certain clerics who obtained permission from their bishops to say breviaries other than those followed in their dioceses, under the pretext that the newer breviaries were better made, he shows the shallowness of this sort of whim: “Scripture, the psalms, and most homilies are the same in all the breviaries. If, to nourish one’s devotion, one needs legenda or some other similar composition from a foreign breviary, one can make use of it for spiritual reading. But how many antiphons seem the most beautiful thing in the world when they stand alone, and so pitiful when one one sees them at their source!”[26]

Later on, he adds these words so full of sense and candor: “A young priest might loudly declare that he recites the Breviary of Paris with greater piety than that of his own diocese, but he would say very quietly that his diocesan breviary is much longer than that of Paris and, even if one did not change any verses or responsories, he would return to his own if one made it shorter than the one whence he finds so much material for devotion. After all, as we have already said, true piety does not disdain proper order. A commonplace thought can nourish it: the less it strikes the mind, the more it touches the heart. The antiphons of the Office of St. Martin come, I think, from Sulpicius Severus. Is there a single one that cannot serve as material for meditation for an entire year? How much force of sentiment there is in these words: Oculis ac manibus in cœlum semper intentus, invictum ab oratione spiritum non relaxabat…. Domine, si adhuc. populo tuo sum necessarius, non recuso laborem… O virum ineffabilem, nec labore victum, nec morte vincendum; qui nec mori timuit, nec vivere recusavit, etc.”[27]

The Ami de la Religion, in its twenty-sixth volume, which we have already cited several times, and the Biographie universelle, mention a dean of the chapter of the cathedral of Montauban named Bertrand de la Tour, a man very attached to the Holy See and zealous for the good of the Church,[28] who after the publication of the Breviary of Montauban by the bishop Anne-François de Breteuil, in 1772, attacked the liturgical innovation and published a collection of twenty-one articles on the new breviaries, a total of 397 pages in-4°. The author discusses the Breviaries of Paris, Montauban, and Cahors in particular.[29] Our attempts to acquire this collection have so far been unfruitful. Thus, we will limit ourselves here to citing the judgment of the Ami de la Religion, which tells us that “the Abbé de la Tour is not generally favorable to the new breviaries, and regrets that they have distanced themselves from the simplicity of the Roman Breviary.[30]”

We do not have any further witnesses among 18th-century French authors against the novelties whose history we are recounting; but these few lines will prove at least that the revolution was not accomplished without protest on the part of many zealous persons who united their voices to those of illustrious prelates whose names we have mentioned. The admissions of Foinard and Robinet are also not without meritOne the other hand, if we wish to inquire about the judgments that have been rendered in foreign countries concerning the serious changes that the 18th century saw introduced in divine worship among the French, it is difficult to find any testimonies expressing such a judgement. The reason is clear: first, because foreigners are not obliged keep up with all the fantasies that cross our minds. Secondly, because when they heard about liturgical uses particular to France they imagined, but since they did not have the new books in their hands, they supposed that these uses not only existed before the Bull of St. Pius V, but indeed went back to the earliest antiquity. We ourselves have found well-educated people who believe this in our own day, even in Rome. Nevertheless, we have found the opinions of three learned foreigners, two Italians and one Spaniard.

The first is the immortal Prospero Lambertini, who later became pope under the name of Benedict XIV. In his great word on The Canonization of Saints,[31] he judges the new breviaries in relation to the authority of the bishops who promulgated them. He severely reprimands Pierre-Jean-François Percin de Montgaillard, bishop of Saint-Pons; Jean Grancolas;[32] and Jean Pontas[33] for having unreservedly sustained that it is within the bishops’ purview to change and reform the breviary, without distinguishing between those dioceses where the Roman Breviary had been followed and those that did not follow the Bull of St. Pius V. Because this question is mainly related to liturgical law, we will keep the explanation and discussion of this passage by Benedict XIV to the part of our work where we will treat this matter in particular.

Giuseppe Catalani, in his learned commentary on the Roman Pontifical, published in 1736, expresses himself with a severity we are unable to translate on the subject of the bishops who incurred the infelicity of lending their trust to heretics for the composition of the breviaries of their churches:

Jam praesertim pro auctoritate breviarii Romani plura possent afferri testimonia quibus abunde ostendi posset, quanta fuerit nuper quorumdam episcoporum insignis audacia atque insolentia, dum illud, inconsulto Romano pontifice, non modo immutarunt, sed et fœdarunt, hœreticisque ansam dederunt constabiliendi suas pravas sententias.[34]

(“In favor of the authority of the Roman Breviary in particular, many witnesses could be brought forward to show the signal audacity and insolence of certain bishops who have recently, without consulting the Roman Pontiff, not only changed this Breviary but employed and entered into pacts with the heretics to establish their false opinions.”)

Finally, the illustrious Spanish Jesuit, Faustino Arévalo, in the interesting dissertation de Hymnis ecclesiasticis he placed at the beginning of his Hymnodia Hispanica, after having reported Benedict XIV’s doctrine on the rights of bishops with respect to the liturgy, adds:

“I have perused a few of these new French breviaries, and I have found many things therein that seem to me worthy of approbation and praise. Yet not on that account am I weary of the Roman Breviary. Rather, I began to hold it in higher esteem after having read several other breviaries. Somehow, what is most excellent in the latter was either taken from the Roman Breviary or formed according to its model.”[35]

Arévalo’s language is a bit less gentle with regard to the new breviaries in the critique of Jean-Baptiste de Santeul’s hymns we have placed at the end of this volume: “In the course of this century, there have appeared in France so many new breviaries, and one finds in the Mercure de France, in Dinouart’s Journal, and in Zaccaria’s Bibliotheca ritualis such a number of works and dissertations on particular offices, on the form of the canonical hours, and on the litany and recent hymns to Our Lady, that one might be tempted to fear that in France, just like women ceaselessly make up new fashions for their clothes, so do priests invent new breviaries each year which please them only because of their novelty.”[36]

[Conclusion]

But it is time to conclude this chapter with the following considerations:

- Such was the upheaval of ideas in the 18th century that one sees prelates oppose heretics and, at the same time, by some inexplicable zeal, undermine tradition in the sacred prayers of the Missal. They profess that the Church has her own proper voice, and then silence this voice by giving the floor to anyone with learning but no authority.

- Such was the naïve effrontery of the new liturgists that they, in agreement with each other, proposed nothing less than to bring the Church of their times back to the true spirit of prayer, to purge the liturgies of all that was unrefined, inexact, immoderate, dull, difficult to give good sense to—everything that the Church, in the pious movements of her inspiration, had infelicitously composed or adopted.

- Such was, in the fairest of judgements, the barbarity into which Frenchmen fell in matters of divine worship, that, since liturgical harmony was destroyed, music, painting, sculpture, and architecture, which are the tributary arts of the liturgy, followed in a decadence that has only increased with the passing of time.

- Such was the abnormal situation into which the innovators placed the liturgy in France that they themselves testified against their work, and joined the defenders of antiquity in regretting the loss of the Gregorian books.

NOTES:

[1] Peter Raedts, “Prosper Guéranger O.S.B (1805–1875) and the Struggle for Liturgical Unity,” 336.

[2] O’Malley, 74.

[3] Raedts, 337.

[4] French theologian, one-time Curé of Calais

[5] Projet d’un nouveau Bréviaire, p. 189

[6] De Moléon’s Voyages Liturgiques makes special mention of which chapters still sang from memory, as if singing from books was still a fairly recent phenomenon.

[7] It is true that in the 1950s, people in Brittany still sang Sunday Vespers by heart, and in many places the Requiem Mass was known, as Domenico Bartolucci recalls:

“When I was a boy I remember that the people used to sing in church. They sang at Vespers (all from memory: the antiphons, psalms and hymns); they sang at devotional functions (Way of the Cross, Marian devotions, etc.); they sang in processions (the Magnificat, Te Deum, Lauda Sion, and other hymns); they sang even at Solemn Mass sometimes. (When I was a boy, each Sunday at my little church there was a Solemn Mass, and on normal Sundays the people sang by themselves.)” I used to sing too, either behind the altar with my father, who was the parish cantor, or with the people in the pews whenever there weren’t cantors behind the altar. The people sang: they sang in a loud voice, a song that centuries and centuries had handed down to them, a lusty song, severe and strong, that the children had learned from their elders, not at school desks or examination rooms but by constant habit, in the continuous practice of the Church. How can I recall without a still-living emotion the participation of all of people at the Liturgy of the Dead, and especially in the Obsequies? Everyone, I mean everyone, belted out the Libera me Domine and then the In Paradisum and then the De Profundis…! Everyone! And the music, that gorgeous music, attained an unmatchable power; the last, deep, hearty farewell to the dead as he left the church where countless times he had sung full-throatedly the praises of God! The people sang!”

[8] This situation is a remarkable parallel to the state of affairs in the Roman church in the 20th century, where the complete revision of the Mass and Office propers required the composition of thousands of new pieces; a work still not even near completion fifty years later, either in Latin or in the vernacular languages. The Neo-Gallicans had this at least to boast, that they tried to replace the former melodies with true chant, rather than taking the folk music ready at hand.

[9] “Finding [men] blameless in peace,” 2 Peter 3:14. Perhaps he is elliptically and sarcastically suggesting that these composers would have had to have been people found “before [the Lord] unspotted and blameless in peace.”

[10] To be fair, this was done in the composition of new Offices since the Middle Ages; e.g., it is the case for the antiphons for Trinity Sunday and for Corpus Christi.

[11] Traité théorique et pratique du plain-chant appelé Grégorien, pp. 4-5

[12] Composers of plainchant.

[13] Traité historique et pratique sur le Chant ecclésiastique, p. 50

[14] He is not entirely correct, since we know that chant was original rhythmic. The prevailing idea in the Solesmes school in Dom Guéranger’s time was that all the notes in a chant piece had the same basic value and that any variation would be based on the text (e.g. syllables at the ends of phrases would make those notes a bit longer). Therefore, when the reformers changed the prose text, they had to change the music too, adding or deleting notes, and the results were usually infelicitous.

[15] It was the only musical proper this Missal retained (besides the sequences) whose text was not taken from Scripture.

[16] The regency between 1715 and and 1723, when King Louis XV was a minor and the Kingdom was ruled by the Philippe d’Orléans.

[17] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, A Complete Dictionary of Music, translated by William Waring, pp. 65-66 (1779)

[18] François-Joachim de Pierre de Bernis, a friend of Madame de Pompadour in the court of Louis XV, and whose famous witticisms were admired by Voltaire. He later became Archbishop of Albi and a Cardinal.

[19] Begun in 1676.

[20] Begun in 1646.

[21] The Revolution interrupted its construction, and it was finished by Napoleon in 1806 as the Temple to the Glory of the Great Army. In 1842, King Louis-Philippe had it consecrated as a church.

[22] 1774-1784

[23] Foinard. Projet d’un nouveau Bréviaire, page 64.

[24] Page 93.

[25] Robinet. Lettre d’un Ecclésiastique à son Curé sur le plan d’un nouveau Bréviaire, page 2.

[26] Collet. Traité de l’Office divin [1822], page 92.

[27] Ibidem, page 106.

[28] L’Ami de la Religion, tome XXVI. Sur la réimpression du Bréviaire de Paris, page 294.

[29] Recall that the Breviary of Cahors was Robinet’s, and also followed in Carcassonne and Mans.

[30] L’Ami de la Religion. Ibidem. —Les mémoires canoniques et liturgiques de l’abbé de la Tour ont été publiés en 1855 dans le septième volume de ses œuvres, réimprimées par l’abbé Migne. (Note de l’édit.)

[31] De Servorum Dei Beatificatione et Beatorum Canonizatione, lib. IV, part. II, cap. XIII.

[32] A theologian of the Sorbonne.

[33] A moral theologian.

[34] Catalani. Commentarius in Pontificale Romanum, tome I, p. 189. We offer this translation with all due respect to Dom Guéranger.

[35] Nonnulla ego istiusmodi breviaria pervolutavi, ac multa reperi in eis, quas approbatione, et laude digna mihi visa sunt; non idcirco tamen breviarii Romani me tœdet, imo pluris hoc habere cœpi, ex quo diversa alia perlegi, ac nescio quo pacto partes illae, quae in ceteris potissimum eminent, aut ex breviario Romano desumptae sunt, aut ad hujus similitudinem effictae. (Arevalo, Hymnodia Hispan., page 211. Dissert. de Hymnis eccles., § XXXII.)

[36] Tot nova Breviaria hoc seculo in Gallia prodierunt, tot opuscula, et dissertationes de officiis singularibus, de precibus horariis universe, de litaniis, hymnisque recentibus Deiparae in Mercurio Gallico, in Diario Dinouartii, in Bibliotheca rituali Zachariae indicantur, ut possit aliquis subvereri ne in Galliis, ut feminœ novas vestium formas, ita sacerdotes nova breviaria quotannis inventant, in quibus vel sola novitas placeat.

A couple of questions:

1 – Could you elaborate a bit on Gregorian chant having rhythm? I had always hear that it did not (as D. Gueranger mentions). Have recent studies brought this to light? Forgive me, but I am quite ignorant when it comes to chant.

2 – Were the Neo-Gallican rites adopted in French dioceses that used the Roman rite? Or were they revisions of local uses?

LikeLike