A Brief Presentation of the Ambrosian and Eusebian Rites

By Henri de Villiers

This article was originally posted on the website of the Schola Sainte-Cecile, and is translated and published here with the gracious permission of the author.

The Liturgy of the Church of Milan: St. Ambrose and the Origin of the Ambrosian Rite

The Ambrosian rite, also called the Milanese rite, is the proper liturgy of the Church of Milan and of certain churches that gravitate in its orbit. This particular western rite is currently used by around five million faithful who live in the diocese of Milan (with the exception of some parts of the diocese that have long followed the Roman rite, the most notable being the city of Monza) as well as in certain parts of the neighboring dioceses of Como, Bergamo, Novara, Lodi, and of Lugano in Switzerland. In the Middle Ages, the rite had a slightly larger extension, and there were even attempts to have it adopted in Prague and Augsburg!

The Ambrosian rite, also called the Milanese rite, is the proper liturgy of the Church of Milan and of certain churches that gravitate in its orbit. This particular western rite is currently used by around five million faithful who live in the diocese of Milan (with the exception of some parts of the diocese that have long followed the Roman rite, the most notable being the city of Monza) as well as in certain parts of the neighboring dioceses of Como, Bergamo, Novara, Lodi, and of Lugano in Switzerland. In the Middle Ages, the rite had a slightly larger extension, and there were even attempts to have it adopted in Prague and Augsburg!

The qualifier “Ambrosian” signifies, of course, that the founder and patron of this rite is St. Ambrose († 387), the great 4th century bishop of Milan. We know for certain that this saint, one of the four great doctors of the western Latin church, arranged the liturgy of his church. From the witness of St. Augustine (Confessions 9.7) and Paulinus, deacon and secretary to St. Ambrose, we know that the holy bishop introduced antiphonal psalmody into his church, modeled on the Eastern practice that originated in Antioch: two choirs chanting the psalms in an alternating dialogue, verse by verse. At that time St. Ambrose was in open confrontation with the Empress Justina, who wanted to take one of the basilicas of Milan and give it to the Arian heretics. The holy bishop had the people of Milan peacefully occupy the church, organizing chanted offices night and day until the danger had passed. Until then, the Latin west knew only two archaic forms of chant, in directum (all the verses sung one after the other without alternation) and responsorial (a solo cantor sings the verse, to which the people respond with a refrain, the response). Upon founding these night and day offices, St. Ambrose also composed hymns he made his people sing, also on the model of what was done in the East, and this was also a major innovation in the history of the whole western liturgy. Many of these hymns composed by St. Ambrose—all in strophes of four octosyllablic lines, in acatalectic iambic dimeter, a simple, lively meter easy to memorize)—were later received in the Roman liturgy and are still sung today. For example, the Aeterne rerum Conditor, mentioned by St. Augustine and used by the Roman rite at Sunday Lauds, appears at the beginning of the night office in the Ambrosian Breviary:

Ætérne rerum Conditor,

Noctem diémque qui regis,

Et témporum das témpora

Ut álleves fastídium.

It might cause surprise that St. Ambrose—who seems never to have gone to the East—made such innovations in the liturgy of his church by taking up customs from Antioch or the East in general. One should also observe that, on the whole, there exist numerous points of contact between the Ambrosian liturgy and the Oriental liturgies, Antiochene and Byzantine. One might also not improbably detect the influence of St. Ambrose’s predecessor, Auxentius of Milan, an Arian heretic imposed by the imperial power, a Cappadocian ordained a priest by his compatriot Gregory of Cappadocia, the Arian archbishop of Alexandria. But this point will always remain a mystery.

It might cause surprise that St. Ambrose—who seems never to have gone to the East—made such innovations in the liturgy of his church by taking up customs from Antioch or the East in general. One should also observe that, on the whole, there exist numerous points of contact between the Ambrosian liturgy and the Oriental liturgies, Antiochene and Byzantine. One might also not improbably detect the influence of St. Ambrose’s predecessor, Auxentius of Milan, an Arian heretic imposed by the imperial power, a Cappadocian ordained a priest by his compatriot Gregory of Cappadocia, the Arian archbishop of Alexandria. But this point will always remain a mystery.

In two celebrated treatises, De Mysteriis and De Sacramentis, St. Ambrose explains the sacraments of Christian initiation to catechumens: Baptism, Chrismation, and the Eucharist, and gives incidental details on the manner in which the sacraments were administered in Milan. The current Ambrosian rite conserves numerous traits described in these works. Most particularly, a passage from the 4th book of De Sacramentis gives us the most ancient known text of the Canon of the Mass. This Canon—whose kinship with the Egyptian liturgy is doubtlessly linked to the fact that the evangelist St. Mark preached in Aquileia and then in Alexandria—was adopted by the churches of Italy very early on, and eventually became the famous “Roman Canon,” of which Milan has always used a proper version that is nevertheless very close to that used in Rome. One can also glean from other works by St. Ambrose, especially in his correspondence, numerous details relating to the liturgy or to ecclesiastical discipline in general, such as ordinations, the consecration of virgins (a ceremony on a vast scale), prayers for the dead, and the dedication of churches.

St. Ambrose’s successors continued his work, particularly St. Simplician, his immediate successor, and St. Lazarus (438-451), who established the three Rogation Days after the Ascension (and hence before their adoption in Gaul by St. Mamertus in 474).

Nonetheless, besides these scattered facts drawn mostly from St. Ambrose’s biography, no major document about the Ambrosian rite exists before the 9th century. Let us now see why.

The Struggle for the Preservation of the Ambrosian Rite

Charlemagne had continued the policy of his son Pepin the Short, eradicating the ancient Gallican liturgy from his domains in favor of the rite of the Church of Rome, and wanted to do the same to the Milanese rite. According to an 11th-century chronicler, Landulphus, the struggle for the suppression of the Ambrosian rite was a bitter one, but the people of Milan resisted so resolutely that it was decided to perform an ordeal: the two books, Roman and Milanese, were placed on the altar of St. Peter in Rome, and it was decided that the one that was found open at the end of three days would be the victor. But both books were found open and, thanks to this miracle, the Ambrosian rite earned its right to survive. All the Ambrosian books had already been destroyed, but the clergy of Milan edited a complete handbook for their liturgy from memory. Say what we may about the historicity of these facts as reported by Landulphus, it is nevertheless certain that, unlike the Roman rite, we possess no document of the Ambrosian rite anterior to the reign of Charlemagne, and for this reason, it is very difficult to retrace its ancient history and understand the stages of its development.

But the battle had not been won yet: Pope Nicholas II, who had tried in 1060 to abolish the Mozarabic rite, sought to do the same with the Ambrosian, aided in this unhappy task by St. Peter Damian. But the rite was rescued by his successor, Pope Alexander II. Pope St. Gregory VII (1073 † 1085) repeated the attempt at suppression, but in vain. Branda da Castiglione († 1443), a cardinal and legate of the pope in Lombardy, failed once again to Romanize the Milanese. The survival of the rite would only be definitively assured by the untiring work of St. Charles Borromeo († 1584), the great archbishop of Milan and hero of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, who sedulously strove to put his diocese’s rite into good order. One might compare his work to what was accomplished simultaneously by St. Pius V for the Roman rite in establishing a standard edition.

But the battle had not been won yet: Pope Nicholas II, who had tried in 1060 to abolish the Mozarabic rite, sought to do the same with the Ambrosian, aided in this unhappy task by St. Peter Damian. But the rite was rescued by his successor, Pope Alexander II. Pope St. Gregory VII (1073 † 1085) repeated the attempt at suppression, but in vain. Branda da Castiglione († 1443), a cardinal and legate of the pope in Lombardy, failed once again to Romanize the Milanese. The survival of the rite would only be definitively assured by the untiring work of St. Charles Borromeo († 1584), the great archbishop of Milan and hero of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, who sedulously strove to put his diocese’s rite into good order. One might compare his work to what was accomplished simultaneously by St. Pius V for the Roman rite in establishing a standard edition.

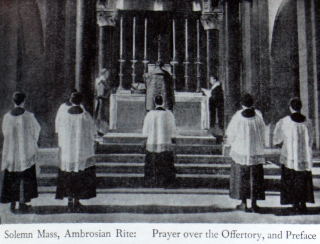

The Ambrosian Mass and its Principal Characteristics

To begin with, the Ambrosian Mass has preserved a number of archaic features that, in many cases, testify to the practice of the Italian churches of the 4th century. Furthermore, studying it permits us to speculate about the state of the Roman rite before the age of Gregory the Great (6th century).

As in all the churches of the ancient Carolingian domains, the Mass begins with the prayers at the foot of the altar, which permit the celebrant and his assistants to put themselves in the proper condition for the celebration of the holy mysteries. Shorter than in the Roman rite, these prayers consist principally of the confession of sins.

The Mass of Catechumens begins with an antiphon called the Ingressa, corresponding to the Roman Introit. But this antiphon is chanted alone, without a psalm verse or Gloria Patri. (The addition of a psalm to the Introit to fill the time during the long processions of the Roman clergy accompanying the pope appears to be an innovation of Pope St. Celestine I († 432). We retain only the first verse, but the whole psalm would once have been chanted.) This antiphon corresponds also to the antiphon of the Byzantine Little Entrance, imported from the Syrian Rite of Antioch.

The celebrant greets the people with the Dominus vobiscum (these are very numerous in the Ambrosian rite), then the Gloria in excelsis Deo is sung, followed by a first (there will be many others) triple Kyrie eleison (without Christe eleison, a Roman peculiarity unknown elsewhere). The first prayer follows, the Oratio super populum, which corresponds to the Roman Collect (moreover, the two rites share many texts of this prayer).

Next the Mass includes three readings—a prophecy, an epistle, and a gospel—a fact attested by the writings of St. Ambrose and corresponding to the ancient practice of Gaul and Spain. (Rome followed Byzantium in having only two readings.) On the feasts of saints, the prophecy sometimes was a reading recounting the life of the saint. The prophecy is followed by a psalmellus, a showpiece for the chanters, whose responsorial structure corresponds to the Roman Gradual, the Byzantine Prokimenon, the Ethiopian Mesbak, etc. A “Halleluia” (respecting the orthography of the Ambrosian books) with verse is chanted before the Gospel. This chant, especially at the final reprise, is often an occasion for extraordinary developments, with melismas much longer than the Gregorian Alleluias and which recall the jubilus, the rejoicing described by St. Augustine.

After the Gospel the Mass of the Faithful begins with a Dominus vobiscum followed by a triple Kyrie eleison. The choir then chants an antiphon called the Post evangelium but which corresponds to the first part of the Offertory, while the bread and wine are brought to the celebrant (originally by ten old men and ten old women supported at the Church’s expense). This antiphon corresponds to the Great Entrance of the Byzantine liturgy. (On Holy Thursday, the Post evangelium antiphon for the day is the famous Cœnae tuæ, which is also the Great Entrance of that day in the Byzantine rite.)

Then the deacon chants Pacem habete, to which the people respond Ad te, Domine. At this point originally the kiss of peace took place, as in all the Christian liturgies with the notable exception of the Roman and African, which put the kiss of peace after the Canon and before the communion. The priest then says a second prayer super sindonem (over the shroud, the great corporal that covered the oblations as a figure of the burial of Christ). This prayer, which existed in the ancient Gallican rite, corresponds to the prayer of the veil in the eastern liturgies of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The choir then chants the Offertorium of the day, whose form is close to the corresponding chant of the Roman liturgy. During this chant, the celebrant presents the oblation of bread and wine, saying in a low voice the offertory prayers typical to the churches of the ancient Carolingian domains and similar to those employed by the Roman rite. He also incenses the oblations, as the Roman rite does in the same place (but the Milanese retain the spectacular ancient 360° rotation of the thurible, without a cover).

Having finished the offertory, the celebrant greets the people with a Dominus vobiscum, after which the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Symbol is chanted. The placing of the Symbol corresponds to that of the Eastern rites, just before the Eucharistic anaphora. The Roman rite has—somewhat clumsily—anticipated the Creed before the offertory, thus before the (theoretical) dismissal of the catechumens, a fact that betrays its relatively late introduction (in the 11th century, when there were no more catechumens). The Milanese Credo differs from the Roman by a slight textual variant: ascendit ad cœlos instead of ascendit in cœlum. After the Credo, the celebrant says a third prayer super oblata, which corresponds to the Roman Secret and is also linked to the Preface dialogue (identical to the Roman) and the beginning of the Canon. As opposed to the sobriety of the Roman Rite after St. Gregory the Great, the Milanese Preface is different for nearly every Mass, as in the Gallican and Mozarabic rites. The Canon, by contrast, is fixed and very similar to the Roman canon, with some variation of details. As we pointed out earlier, the Roman and Ambrosian Canons are certainly two forms of a canon that was widespread in Italy in the 4th century, probably originating in Aquileia.

After the Canon, the celebrant proceeds to the fraction of the Body of Our Lord, while the choir chants an antiphon called the Confractorium. (The text for these antiphons is often found in the Roman Communion antiphons, whose introduction in Rome was rather late: 6th century). Next comes the Pater noster chant. We know that in Rome it was Pope St. Gregory the Great who displaced the Pater and put it at the conclusion of the Canon, before the fraction, in imitation of Constantinople. It is probable that following this reorganisation, the ancient antiphons that had accompanied the fraction of the bread were recycled as antiphons to accompany the faithfuls’ communion.

In imitation of Rome, the Milanese rite also introduced a second kiss of peace at this point, duplicating the one at the beginning of the offertory. As the peace is being passed, the choir can chant an antiphon for the peace (“Pax in cœlo, pax in terra, pax in omni populo, pax sacerdotibus ecclesiarum Dei.”), which is not absolutely prescribed, but has a counterpart in the antiphona ad pacem of the ancient rite of Gaul and the Roman Agnus Dei.

The choir accompanies the faithful’s motion during the communion with a very curious and often very original piece called Transitorium. Its style differs markedly from what is found in the Roman rite at this point, in text as well as music. A final prayer post communionem is chanted by the celebrant. After three Kyrie eleison, the dismissal is made, not employing the Ite missa est but the following responses: V/. Procedamus in pace R/. In nomine Christi. V/. Benedicamus Domino. R/. Deo gratias. The Benedicamus Domino must have been a more ancient formula than the Ite missa est: it is the only form known in the Ambrosian rite and is employed in the Roman office and Roman penitential masses (Advent, Lent), which generally preserve more ancient elements.

Like the Roman Mass, a trinitarian benediction of the faithful by the priest is added after the dismissal, along with the Last Gospel, which is the beginning of the Gospel according to John, as in Rome.

The Ambrosian Liturgical Year

The liturgical year, as in Gaul or Spain, begins with the feast of St. Martin on 11th November. Ambrosian Advent comprises six weeks (as opposed to four in Rome) and begins on 12th November at the latest.

Preceded by Septuagesima, Lent begins on the Monday that follows the first Sunday In capite Quadragesimæ (as was the case also in Rome before St. Gregory the Great anticipated it on Ash Wednesday). The following Sundays are designated by the Gospel read on that day: of the Samaritan, of Abraham, of the Blind Man, of Lazarus, and then Palm Sunday. Holy Week is radically different in structure from the Roman practice. Saturday is not a fasting day, contrary to Rome but in conformity with the East.

There are fifteen Sundays after Pentecost, then five Sundays “After the Decollation” (of St. John the Baptist) and two Sundays of October. The third Sunday of October celebrates the Dedication of the Cathedral, followed by three Sundays “post Dedicationem.” The chant pieces proper to these Sundays are chosen from a common repertoire (“Commune dominicale”) and may be used many times.

The sanctoral cycle includes many Milanese saints, of course, but also many Roman martyrs from the first centuries, many of which are not celebrated by the Roman rite (such as St. Genesius, a Roman martyr whose feast we will sing this coming 25th of August).

The Ambrosian Divine Office

Let us conclude with a quick word about the divine office.

The most ancient structure is that of the night office, which has three Nocturnes joined to an office of Matins, which was formally divided into two distinct parts—under the more modern names of Matins and Lauds—by St. Charles Borromeo. The night vigils of Saturday and Sunday have proper structures and include many canticles from the Old Testament, like the Palestinian office or that described in the rule of St. Benedict. The night office of Saturday uses Psalm 118, as the Byzantine office. The psalms for the other days of the week, from Monday to Friday, are divided into a two-week cycle. Lauds begins with the Benedictus and ends, as in every Christian liturgy, with the daily singing of psalms 148, 149, and 150, to which Milan adds psalm 116.

The other hours (Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline) are similar to the Roman practice, which would have been common in Italy (the rule of St. Benedict is an adjustment of this common practice, with some simplifications—such as the reduction of Vespers to four psalms—to facilitate the monks’ work): psalm 118 is—as in Rome—chanted every day, split up over the little hours. Vespers opens with a Lucernarium responsory followed by five psalms as in Rome (the Vespers of feasts have a much more complex and original structure, with a regular repetition of psalms 132, 133, and 116). At the end of Lauds and Vespers, the singing of select psalm verses is comparable to the Byzantine aposticha (which originate in the liturgy of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem). Compline has six psalms every day (4, 30, 90, 132, 133, 116), somewhat like the Byzantine Great Compline.

The Latin version of Biblical texts employed by the Milanese rite does not follow the usual Vulgate of St. Jerome nor the so-called Gallican Psalter.

Ambrosian Plainchant

The panorama we have quickly sketched of the riches and peculiarities of the Ambrosian rite would be incomplete without also mentioning Ambrosian chant—of such a strange and peculiar taste. Suffice it to note that this chant is obviously more archaic in its modal constructions than Gregorian chant and yet shows many points of resemblance with the so-called Old Roman chant. Gregorian chant is in fact the result of a later reform, a deliberate effort of simplification and systematization, while the Ambrosian and Old Roman chants have manifestly preserved a more archaic form of the ancient cantillation of the churches of Italy.

A Neighboring Rite: the Eusebian Rite

A great friend of St. Ambrose and, like him, a champion in the struggle against the horrors of the Arian heresy, St. Eusebius of Vercelli was bishop of that city in Northern Italy until his death in 371. At that time, this diocese included the whole Cisalpine region and was a suffragan of the archbishop of Milan. Unlike Milan, Vercelli seems not to have been able to maintain its own rite, and Charlemagne seems to have succeeded in imposing the Roman rite upon it, whereas he had failed to do the same to the Milanese liturgy. As in all the other dioceses of the Carolingian empire, the Roman liturgy developed subsequently in an autonomous fashion, so that one may speak of a Roman liturgy of the use of Vercelli, one of the particular uses of the Carolingian domains, alongside the Lyonese rite, the Parisian rite, the rite of Nidaros, of Sarum, etc., etc.

This medieval liturgy of Vercelli was called the “Eusebian Rite” in imitation of the neighboring Milanese rite. It is known to us from the exceptional archives of the Vercelli cathedral chapter, very rich in important manuscripts. Though fundamentally Roman in structure, the liturgy of Vercelli also had numerous borrowings from the neighboring Ambrosian rite and preserved very many unique traits, which either bear witness to an archaic form of the Roman rite or were totally unique, originating before the Carolingian romanization (such as the famous Eastern antiphon Sub tuum præsidium, whose Eusebian text is a Latin translation that differs from both the Roman and Milanese). The late Abbé Quoëx († 2007) understood the great contribution that study of the liturgical books of Vercelli could make for our understanding of the history of the Roman liturgy, and had made a review, classification, and study of them for the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, but his death brought an end to this project.

Only printing its breviary in 1504, Vercelli preserved its own rite until its suppression in 1575. On the one hand, Savoy, who had conquered the territory, wanted to unify the subjects of its states through the common practice of the Roman rite alone, according to the Tridentine books; on the other, like many dioceses in that period, economic considerations were the most important: the publishing and printing costs of all proper liturgical books was enormous for a single diocese, since printers were confronted with a very weak commercial outlet on the very narrow diocesan market, while the Roman books were spreading quickly and were not expensive. Thus the rite disappeared, but certain elements were long preserved by popular tradition for the Feast of St. Eusebius.

Be that as it may, on August 21st we will sing the office of Vespers within the Octave of the Assumption according to the ancient use of Vercelli, the chant having been reconstructed on the basis of the renowned medieval manuscripts of the chapter. We will also use the polyphonies composed by Orazio Colombani, a choirmaster of the cathedral of Vercelli in the 16th century.

Thanks a lot for the translation!!!!!!

LikeLike

Was the imposition of the Roman rite a political decision? Were different liturgical rites seen as a threat to political dominance?

LikeLike

Which case do you refer to exactly?

LikeLike

In the cases of the Ambrosian and Mozarabic rites, for example.

LikeLike