Notkerus’s translation of an article appearing in the Revue et Encyclopédie Multimédia des Arts (Académie Royale de Belgique), which is a summary made by Charlotte Donnay of her master’s thesis entitled “Les jubés de la Renaissance dans les Pays-Bas méridionaux.” See the original for detailed footnotes.

INTRODUCTION

In this article, we have sought to understand the reasons that led to the appearance of the jubé in the beginning of the 12th century in Christian churches, and to follow the evolution it underwent in the course of the centuries. Aware of the formal, stylistic, iconographic, chronological, and material differences inherent to each region, we shall not attempt to write an exhaustive and linear history of jubés, any more than we should intend to be reductionist about the diversity of their functions. We intend, rather, to sketch the development of these monuments and give an account of their diversity of function—today, alas, often underestimated.

HISTORY: FROM THE AMBO TO THE JUBÉ

In Latin, the jubé is dubbed pulpitum, a term used during the Middle Ages and a long time thereafter in different regions. The French term jubé comes from the imperative of the Latin verb jubere, wherewith begins the formula Jube domne benedicere, addressed to the bishop by the deacon before ascending to the jubé to sing the Gospel. In the southern Low Countries, the French term is not used, and the jubé is often called doxale, doxaal. Jan Steppe states that the term comes from the Latin dorsale, dossale, meaning “choir”. In the 18th century, Canon Waucquier of the cathedral of Tournai gave another interpretation of the term similar to that of Steppe:

“That which in proper French one calls jubé, taken from the Latin, we in Tournai and Wallonia call the doxale; Raissius [in the 17th century] writes, ambonem chori (quem vernacule Doxale vocamus). I have searched for the origins of this word, and it seems to me that, sticking to the letter, it cannot but naturally derive from doxa, a Greek word meaning ‘glory’, as is well known. As a result, doxale was coined to signify this elevated and most striking place in our churches, which serves as much to embellish them as to render more audible the voices of those who ascend them to sing the lessons, Epistles, Graduals, and Gospels. Another thought that comes to mind is that it should be dorsale rather than doxale, which is also better; because in the choir one rests against what in our French we call doxale. Perhaps, then, we ought to say dorsale, from the Latin dorsum, meaning ‘back’ […]”

It appears, therefore, that in Hainaut and in the region of Tournai, the most common term for the jubé was doxale. However, as Steppe states, the terms lincener, lichenier, lissené are also attested; they derive from the Dutch lessenaar, meaning “lectern” or “pulpit”. In Tournai, certain writings show that these terms were used in the 16th century, especially to refer to the jubé of the cathedral of Notre-Dame:

“To Jehan de Laoultre, jeweller and chandler, the wax candles that were placed and lit around the reliquaries placed in front of the lichener of the church of Notre-Dame on the last day and feasts of Pentecost in the usual way […]”

In Artois, Jan Steppe reported the names trin or trincq, an aphæresis of the term lectrin from the Latin word lectorium, whence also the German term lettner. In England, the jubé is dubbed pulpitum, “choir screen”, or “roodloft”. In Italy, one still hears the term tramezzo, a word which Marcia Hall renders into English as “partition”, and often translated into French as cloison. These tramezzi were once called pergula or pulpitum. Nevertheless, there are local variants: in Venice, for instance, the jubé of St Mark’s Basilica is called the barco, whereas in Florence, the jubé is called ponte or pontile. These words refer to the actual structure of the jubé.

“The need to secure the division between the sacred and the profane is so profound that screens can be located in nearly every setting where the divine is manifested to man, from primitive shrines to highly organized cult centers.”

In the Catholic faith, and this in continuity with the Judaic tradition, “the sacred space of the celebration surrounding the altar was always very circumscribed and reserved, in forms that varied considerably depending on the place.” This notion of “limit” is inherent to that of the sacred, as has been emphasized by Emile Durkheim, according to whom “the sacred is, in effect, by definition, that which must be held at a distance”.

In the Paleo-Christian age, the choir was generally hidden by a veil. At the beginning of the 4th century, this was replaced in certain places by a balustrade called the cancellum, the chancel. The first reference to such a barrier is found in Eusebius, bishop of Cæsarea, in a sermon he delivered for the consecration of the basilica of Tyre in 315. Eusebius speaks of a simple open wooden balustrade. This evolved into a barrier made up of carved blocks of marble and pillars about a metre high. Archæological evidence of this sort of structure are preserved in the episcopal churches of Trier and Aquileia, built in the 4th century. This sort of structure marks the limit between sacred space and that granted to the faithful, and also to highlight the performance of the Mass and other rituals.

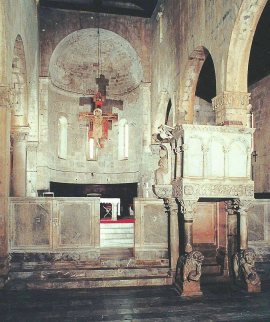

The pillars of the cancellus quickly became taller and surmounted by an architrave. This structure, called the perugia, probably resulted from the fusion of the choir and what in Old French was called the tref, a wooden beam surmounted by a calvary-scene or crucifix and placed lengthwise at the entry of the liturgical choir. From the 9th century, the tref was reinforced by pillars that rested on the enclosure of the lower choir, as is notably shown by the archæological remains of the cathedral of Torcello. This sort of structure that still exists there to-day is likely an 15th-century arrangement using elements sculpted in the middle of the 11th century. Another example of the perugia, dating from the 12th century, is preserved in the church of Santa Maria in Valle Porclaneta in Italy. In this church, near the choir enclosure, there is an ambo. This stone platform with a pulpit was present in Christian churches from the earlier centuries. The parish church of Brancoli in Tuscany, for instance, has preserved an ambo and choir enclosure dating from the 12th century, but partly redone in the 20th century.

In the 12th century, Prevostin of Cremona (c. 1150-1210), a Parisian theologian, mentions the presence of a high wall rising between the religious and the lay faithful. In this way, monks and canons, separated from the world, could live the opus divinum in solitude and silence. Indeed, the canonical order came to define itself based on the monastic model, and therefore cultivate a greater separation from the world. The multiplication of altars in the nave, especially of altars dedicated to the Holy Cross, no doubt reinforced the religious community’s need to reserve a separate place protected from the distractions caused by employing these altars.

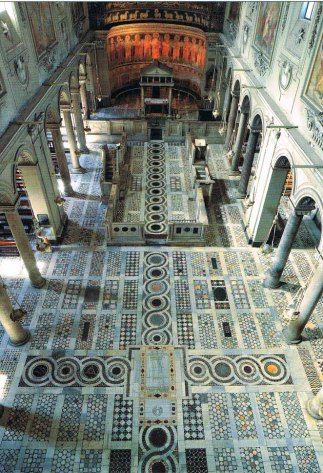

From an architectural perspective, this multipolarity of liturgical space resulted in several cases in the fusion of the western wall of the choir enclosure and the ambo. Jan Steppe cites the example of the church of Beverley in England, wherein in the 11th century Archbishop Ealdred of York built a pulpitum above the choir enclosure. The fresco, representing the Christmas miracle in Greccio painted by Giotto in 1297 in the church of St Francis in Assisi, attests to the fusion between the choir wall and the ambo. The most significant example that is still in place of this type of arrangement is without a doubt the choir enclosure of the Schola Cantorum in the church of St Clement in Rome, a structure dating from the 5th century but modified in the first half of the 12th century. Contrary to what one sees in the church of Brancoli, here the ambo is no longer an separate structure in front of the choir enclosure, but is fused therewith.

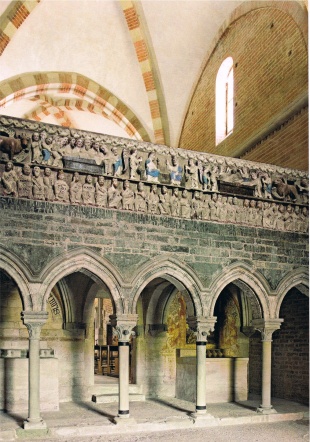

The fusion of the ambo and the choir enclosure is probably at the origin of the erection of jubés at the end of the 11th century. That of the abbey of Vezzolano in Italy, built in 1189, is the oldest that remains. In Germany, after 1139, a jubé was built in the Abbey Church of St Michael of Hildesheim, of which only the north and south walls survive today. Jubés seem to have first been built in cathedrals, collegiate churches, monasteries, and only thereafter in towns of secondary importance and villages. Beginning at the end of the 15th century, certain parish churches, such as that of Saint-Géry in Braine-la-Comte, built jubés not because of functional reasons—given that there were no monks or canons requiring an enclosure—but for formal and “iconographical” reasons. Paul Philippot suggests that the presence of a jubé “answers to the different understandings of space associated with the liturgy and the division of the church into a series of distinct sacred spaces, usually marked by a choir enclosure and side altars or even chapels”. This fragmentation of space led to the need to mark the hierarchical importance of the parts that constituted the sanctuary.

It would seem, therefore, that the jubé was the result of the fusion of the choir enclosure, the tref, and the ambo. This opinion was already expounded in 1919 by Enlart in his Manuel d’Archéologie française. The jubé, he says, is a “portico surmounted by a gallery, which is the result of the fusion and development of the chancel, the ambos, and the tref.” It is most often built in the transept at the entrance of the choir, although its placement can vary according to the size of the religious community. With regard to the very structure of the jubé, it can differ according to the country, the region, and local traditions. In our regions [Belgium] and in France, the jubé usually takes the shape of a platform supported by a gallery consisting of three to a seven arches supported by a bottom wall with one or more doors leading to the choir. The jubés of Chartres (1230-1240) and of Bourges (c. 1230), now destroyed but known through drawings and engravings, are two emblematic examples of this sort of jubé. In France, no 13th-century jubé has survived in its original state, and the most important jubés, such as those of Chartres (1230-1240), Sens (13th century), Bourges (1230), and Amiens (c. 1270), are only preserved in fragmentary form. In the same time period, jubés were also built in the southern Low Countries, most notably in Ypres (1256-57) and Bruges in the collegiate churches of Saint-Donatien (before 1276) and Saint-Sauveur (before 1280). Nothing remains of these jubés.

For reasons yet unclear but apparently linked to a change in the understanding of ecclesial space, many jubés were destroyed in the 16th and 17th centuries. Indeed, in response to Protestant attacks, the Council of Trent (1545-1564) insisted upon the need for greater involvement of the faithful in the celebration of the Mass, which resulted in a new arrangement of sacred space.[1] Gradually, a unified space came to be favoured wherein the altar was immediately open to view. Secondary altars arranged in the nave were then moved to side chapels, thus freeing the central aisle of the nave and allowing for a direct view of the high altar. The church of the Gesù in Rome (1568-1584) is a particularly revealing example of this new sense of space. In the southern Low Countries, this clearer hierarchy of ecclesial space appears only later in the second quarter of the 17th century. From this perspective, jubés were seen by their detractors as obstacles to the visibility of the ritual. As a result, many of them were destroyed, while the more fortunate ones were dismantled and rebuilt on the reverse of the façade. This is the case of the jubés of the churches of Saint-Ursmer in Binche and Saint-Géry in Cambrai, moved in 1778 and 1740 respectively to the reverse of the western façade. As a result, from the 17th century onward, practically no jubés were ever built.[2]

During this Catholic restoration [the Counter-Reformation], the Church hence played an important rôle in the destruction of jubés, which were contrariwise often kept by the Calvinists who incorporated them into their liturgy. The jubé of the cathedral of ‘s-Hertogenbosch (1610-1613) illustrates this phenomenon well: it was only sold to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1866, precisely when the cathedral, which had been held by the Calvinists since 1629, was restored to Catholic hands. The French occupation of the Low Countries between 1792 and 1815 also led to the destruction of many jubés: in Mons, the jubé designed by Jacques Dubroeucq was dismantled in 1798; the sculptures of the jubé of Sainte-Gudule in Brussels were removed in 1793 and the jubé was permanently destroyed in 1804. Nevertheless, interest in the preservation of jubés arose in the course 19th century. Indeed, in 1884, Léon Cloquet published a veritable plea in favour of jubés and the need for their preservation, showing that by then some had taken up the defence of these structures.

FUNCTIONS AND USES OF THE JUBÉ

To separate

As previously mentioned, the raison d’être of the jubé is to separate religious from the lay congregation by marking out a sacred space. The jubé should not, however, be understood as a wall keeping the choir entirely hidden from the faithful. Indeed, many writings of the time attest to religious communities’ desire to offer a certain visibility of the proceedings of the Mass to the faithful, especially during the elevation of the Host. In the 13th century, Odo of Sully, bishop of Paris in 1208, explained that the elevation of the Host must be seen by all the faithful. In a 1249 decree of the General Chapter of the Dominicans, it is established that a window on the jubé be opened during this precise moment of the celebration. To ensure a better view of the elevation of the Host, the religious resorted to visual stratagems. In Chartres, a brightly-coloured curtain was suspended behind the main altar so as to bring out the Host, while in other places, candlesticks were placed on the altar so that their light would accentuate and illuminate the gold altarpieces, setting up the particular conditions appropriate for the staging of the Elevation. Moreover, the opening of the doors of the jubé only at certain moments of the celebration considerably enhance the actions taking place in the choir. Further still, by concealing the view of the choir, the jubé increased the intensity of the rituals and piqued the curiosity of the faithful. The elevation of the Host was a momentous moment of revelation for the faithful, reinforced by the incense and the chants that accompanied it. In Sens, the arches of the jubé are entirely open, giving the faithful a view of the inside of the choir.

Jacqueline Jung explains that we must therefore think of the jubé as an ambivalent structure allowing at once for the unification of two spaces and two different social groups, while marking a neutral space between the two. “Even as the screen distinguishes the physical and symbolic domains of nave and choir, its open portal reasserts the continuity of those realms.” The jubé can hence be understood as a “border marker”, following the definition set down by Van Gennep. The open doors of the jubé that allowed the faithful to see the choir offered them several opportunities to visually access the most sacred space. In this way, the jubé enhances the experience of “passage” that begins at the portal and continues inside the church.

To read and chant

In addition to its rôle of a “divider”, jubé fulfils several functions that can be grouped into two categories. On the one hand, their platform permitted the reading and chanting of the sacred texts, and on the other, they were the place and framework used to stage certain “solemn events”:

The jubé: A Reading Platform

The jubé also serves as the high platform from where the Gospel is chanted and the Epistle is read. Previously, from the early Christian era until the 12th century, the Gospel was chanted from the ambo. Like the latter, the jubé allows the priest to be raised up so that he can read the sacred texts while setting up a sacred space. In his work entitled Dissertations ecclésiastiques sur les principaux jubés des églises, published in 1688, Fr Thiers strove to uncover the origin of this tradition. Already in the 2nd century, St Cyprian wrote, “What was to be done other than go up to the ambo…so that, raised upon this high space, visible to all the people, as is appropriate to its merit, he might read the teachings of the Gospel of the Lord.” Two centuries later, in the Apostolic Constitutions (c. 380), it is also recommend to read the sacred texts from an elevated place. According to the authors, the reasons for this practice are manifold. In the 10th century, in his Treatise on the Sacrament of the Altar, Stephen, bishop of Autun, proffers an allegorical explanation referring to the prophet Isaias: “One reads the Gospel upon the jubé on feast days because he who announces the word of God to Sion is commanded to go up.” In the 10th century, John, bishop of Avranches and archbishop of Rouen, says that the Gospel must be read from on high because it is the sacred text par excellence and must be above the Law and the Prophets. In his Rationale divinorum officiorum (1286), William Durandus writes that:

“The deacon goes up to the jubé to show that Jesus Christ surrounds and protects all those who keep the words of the Gospel, and in order that it might be more easily heard by the faithful. He goes up to it to announce the Gospel out loud and upon an elevated place, for the word of God must be heard in all places and throughout the world. He reads the Gospel on a high and elevated place, because the doctrine of the Gospels has been spread throughout the earth.”

The number of lecterns on the jubé could vary between one and four. In Tournai, the ceremonial-ordinary of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame (15th century) mentions two lecterns on the Gothic jubé built in the middle of the 13th century. The highest one, destined for the reading of the Gospel, was placed on the north, whereas a second was placed on the south for the reading of the Epistle. The Roman Ordo (9th century) indicates that “only the Gospel must be chanted on the higher lectern; and the lower is for the Epistle, Gradual, Alleluia, and Tract.”

According to the historical testimonies gathered by Thiers, dating from the 11th to the 16th centuries, the liturgical ritual preceding the reading of the Gospel seems to have remained constant. After having received the blessing of the celebrant, the deacon takes the book from the altar and kisses it. Then, he places it upon his shoulder to take it up to the jubé. He is preceded by two acolytes each holding a torch, and by three subdeacons of which two carry a thurible and the third the incense. Having arrived to the foot of the jubé, the two acolytes move aside to let the subdeacons and deacon ascend. The subdeacons immediately descend by the second staircase while the deacon goes up to the highest lectern and turns to the side of the male congregation—towards the south or the north depending on the building—to sing the Gospel. Once this is over, the deacon descends from the jubé by the second staircase, gives the book to a subdeacon who takes it to be kissed by the bishop or celebrant.

In his Explanation of the Divine Offices, John, bishop of Avranches and archbishop of Rouen (9th century), explains that only the two subdeacons bearing the thuribles precede the deacon because “… the works of Jesus Christ preceded His doctrine …” He adds that “… the elevated place from where the Gospel is chanted marks the importance of the preaching the word of God … and the two candles that are borne before the deacon signify the Law and the Prophets who preceded the Gospel.”

It is said that to read the Gospel, the deacon turns to the south or the north, depending on where the male congregation is placed. Pope Innocent III, who describes the same ceremony in the 13th century, adds another interpretation: “the deacon turns to the north to drive out the devil and bring the Holy Ghost; and that is what obliges him to arm himself with the sign of the Cross, lest the devil, who sets obstacles to our good works, should deprive him of the attention of the choir, and of the word from his mouth. Thiers mentions that in his time, in the 17th century, the practice of singing the Gospel from the jubé on Sundays and feast days was still in force, both in the West and East. However, in the southern Low Countries, Steppe points out that, from the 17th century, this tradition was becoming rarer and rarer, especially in the churches in Brabant where it entirely stopped, such as Saint-Rombaut in Mechelen in 1603 and Sainte-Gudule in Brussels in 1622. He evinces practical reasons for this: the heavy robes of the priests would have made it difficult to climb up the jubé. This assertion seems a priori unlikely because of the value and importance of this tradition.

From the twelfth century, the gallery of the jubé was also used for preaching. In some Gothic or Renaissance jubés in the southern Low Countries, this use is attested by the presence of a projecting pulpit in the center of the gallery. However, from the end of the 16th century and during the Baroque period, the inclusion of such a pulpit in the gallery became considerably rare. This gradual abandonment is undoubtedly linked to an increasingly frequent use of the pulpit at the end of the 15th century.

From the platform of the jubé, the priest also read the Acts of the Martyrs and the stories of new miracles, exemplary stories to inspire the faithful to imitate the behaviour of the saints and augment their faith in God.

The jubé: A Chanting Platform

In the Middle Ages and the modern era, the jubé was also used as a platform from which to chant. Generally, the singers went up to it to chant on the lesser pulpit the Gradual, the Tract, the Alleluia, the prophecies, the Matins lessons, and the genealogies. Besides these principal chants there were also antiphons, responsories, and versicles which changed according to the season and associated feasts. The 15th-century ceremonial-ordinary of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Tournai mentions the use of the jubé as a chanting platform. During High Mass, the Gradual was chanted on the jubé by two chaplains, the Tract by four boys placed two by two, and the Alleluia either by three canons or by three priests of the main altar. On double feasts, the Gradual was chanted by two subdeacons, the Alleluia by two priests of the main altar, and the Tract, if there was one, by four priests of the main altar, in alternation, two by two. Finally, on nine-lesson feasts, the Alleluia was chanted by two chaplains while the Tract was chanted in alternation either by two subdeacons on the jubé and two deacons on the lectern or by two subdeacons and two deacons on the jubé and two priests of the main altar on the lectern. The number of singers was therefore in proportion to the importance of the feast being celebrated.

During the Counter-Reformation, organ platforms built on the western façade of churches deprived the jubé of this function. As their name suggests, an organ was placed thereon to accompany the singers. In certain cases, jubés were dismantled and rebuilt on the reverse of the façade to act as organ platforms. For this reason organ platforms are sometimes incorrectly called jubés. The jubé of Tournai was preserved in its original location and was likewise used as a platform for singers. As evidenced by a capitular act, in 1637 the cathedral chapter decided to place a small organ there. Howbeit, for an unknown reason, the project was never carried out and eight years passed by before an organ was placed on the jubé. From this moment forth, the jubé fulfilled the rôle of an organ platform until the 19th century, as is shown by a cathedral furniture inventory from 1889, and the statement of Maistre d’Anstaing in 1842, “Not only is the jubé beautiful, but it is still quite useful, destined as it is to host the choir’s music, which is thereby marvelously sung from an elevated place, between the clergy and the people, and whence it can be easily heard by the entire church.”

SOLEMN OCCASIONS

When it served as the base for the exposition of holy relics, all eyes were on the jubé. The Blessed Sacrament was likewise exposed there on Maundy Thursday, palms were blessed there on Palm Sunday, candles on Candlemas, and ashes on Ash Wednesday. In Braine-le-Comte and in Soignies, on Palm Sunday, the adoration of the Holy Cross was performed under the arches of the jubé. In Braine-le-Comte, the procession of relics of St James and St Christopher ended on the porch of the jubé where the reliquaries were given over to be kissed by the faithful.

From the platform of the jubé, the priest likewise gave absolution on Ash Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, and Easter Day. In Tournai, on certain feasts, the jubé was adorned with tapestries and the lamps were furnished with candles. In 1749, Canon Waucquier gave a description of these arrangements:

“At one time—not too long ago—there hung before this venerable Cross that which I shall here call the old choir lamp. It was removed, to all appearances, when the copper one was replaced by one made of silver, which preceded that of the new shape which hangs to-day before the high altar. The older lamps, both the silver one—which seems to have been melted so as to form the modern one—and the copper one—which hung before the great Cross—had, instead of lamps, three dish-shaped basins in the midst whereof there was something to hold a candle. They all hung at an equal distance along an iron rod borne by two chains, also of iron, and which hung down in the manner in which the modern lamp hangs down to-day. Three candles were lit on this lamp in front of the great Cross, during the Little Vespers of the Passion, which were chanted on every Friday of Lent, except the last.”

[….]

Jacqueline Jung also mentions the less common presence of altars atop the jubé, and cites the church of Saint-Étienne in Vienne as an example. In Mons, the account-book of the collegiate church of Sainte-Waudru twice mentions the presence of an altar on the jubé erected by Dubroeucq between 1535 and 1549. In Binche, during the audience of 31 July 1738, there was a discussion about destroying the altar on the jubé platform in order to place an organ there. These two examples corroborate the suggestion that altars were sometimes present on the jubé platform.

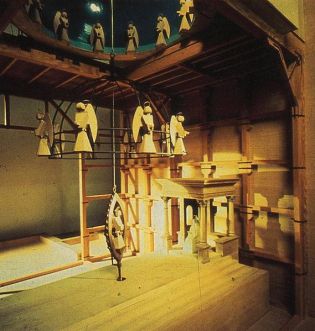

THE JUBÉ: A STAGE FOR MYSTERY PLAYS

In certain places, the jubé platform was used as a stage for Mystery plays. In the church of Santa Felicità in Florence, they were performed on the Annunciation, in Santo Spirito on Pentecost, and in the church of the Carmelites on the Ascension. These “religious plays” were sometimes re-performed for important personalities passing through the Italian city, as evidenced by the account of Abraham, bishop of Suzdal. While staying in Florence during the Council of 1439, he described the representations of the Annunciation and Assumption. During the Annunciation play God, performed by a maquette hidden behind a curtain, sits on a platform built on the reverse of the façade, on the axis of the jubé upon which the Virgin is to read. At a certain point, the curtain falls and reveals God the Father. He sends the Angel Gabriel who flies, via a system of pulleys, over the faithful up to the jubé to carry the divine message to Mary. Once the announcement is made, the angel leaves the jubé at the very moment when a thunderclap sounds. Then, a dove comes down from the vault and all the lights are lit at once to mark the moment of the Incarnation. The device set up for the Assumption required a system of pulleys and a very important ceremony. On the jubé a mountain was built over which the heavens are represented by a cloud suspended on a platform containing a system of pulleys. These allow Christ to be hoisted during His Ascension. At the moment when He disappeared behind the cloud, there was an explosion of lights and sparks in the church. But Christ’s Ascension was not yet over: when he arrives near His Father, the music stops, the lights go out, and a curtain hides the heavens. The Apostles and Mary wait on the jubé. The angels come down thither to announce the good news from Heaven.

According to Marcia Hall, this tradition disappeared at the end of the Quattrocento. These theatrical representations also took place in our country. The feast of Pentecost was notably celebrated by letting a dove fly into the church, symbolizing the Holy Ghost. This custom is attested in the church of Sainte-Waudru in Mons, in the church of Saint-Géry in Braine-le-Comte in 1599, in the church of Saint-Jacques in Tournai, and in the collegiate church of Sainte-Begge in Andenne in the 18th century. These ceremonies were doubtlessly of lesser importance than in Florence, but they attest to the more splendid celebration of certain feasts.

THE JUBÉ: A PLATFORM FOR RELIGIOUS ANNOUNCEMENTS

The documents show that the jubés were also used as a place of communication between the religious and the laity: “jubés were the places from where the faithful received the announcements of all things they had an interest in knowing”. From the jubé, the priest informed the faithful of the different dates and seasons of the liturgical kalendar. For instance, Easter Day and the season of Lent were announced around Christmas. In Soissons, even the foods one could eat during Lent were proclaimed. The days when laymen had to make their confession were also announced from the jubé.

THE JUBÉ: A PLATFORM FOR ECCLESIASTICAL JUDGEMENTS

When serious misdeeds were committed, the jubé was the platform whence the names of the excommunicated were proclaimed such that they were known to all. Thiers reports that after the looting of the house of the dean of Chartres in 1210, the whole town was put under interdict by the chapter, which excommunicated everyone connected closely or distantly to the looting: “Every day the Hebdomad went up to the lectern and, with extinguished candles and ringing bells, excommunicated those who were connected to this deed. The same was done in all the parishes.” Culprits were denounced from the jubé, but the accused also defended themselves from the accusations on the same place. Atop the platform of the jubé, the accused, heard and seen by all, swore his innocence on the Bible.

THE JUBÉ: A PLATFORM FOR THE PRESENTATION OF BISHOPS

Upon the election of a new bishop, he was presented publicly to the faithful gathered in the nave from the top of the jubé. This presentation ceremony is attested in Mayence, in Worms, and in Chartres. In our country, it is attested in the 17th century in Tournai: “and forthwith, the cantor, from his stall, entones the hymn Te Deum laudamus. Once this hymn is sung, the Dean leads the Lord Bishop to the jubé and, thence, Canon Waterloop reads and announces the bull to the people, standing atop the platform, and adds a small prayer.” Nevertheless, Anne Dupont and Florian Mariage emphasize the “more theoretical than actual” nature of this “episcopal” rôle of the jubé in Tournai. Indeed, in the 18th century, the height of the jubé prevented the voice from being adequately heard, and a mobile pulpit was placed on the central arch of the jubé for the bishop to preach during his presentation. The writings of Maistre d’Anstaing in 1842 confirm the assertions of Canon Waucquier. Maistre d’Anstaing states that, at his time, the bishop no longer preached during this ceremony, but rather a canon went up the jubé to read the bulls of institution of the new bishop. However, the jubé remained, until the 19th century, a “backdrop” for the presentation of a new bishop.

THE JUBÉ: A PLATFORM FOR POLITICAL EVENTS

In Germany as in France, the presentation of the new sovereign was made atop the jubé. In Rheims, Henry II was proclaimed King of France on 26 July 1547 from the jubé of the cathedral, as was Louis XIII on 17 October 1610 and Louis XIV on 7 June 1654. The jubé was likewise the stage for major political events, such as the reconciliation between John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, and the children of the Duke of Orléans in 1409.

CONCLUSION

The appearance of the jubé in the 12th century in Christian churches seems therefore to have been the result of the fusion between the ambo and the choir enclosure. The jubé allowed the sacred space of the choir to be marked out, as well as to show the hierarchical distinctions between the different spaces of the sanctuary. Until the beginning of the modern age, it was a fundamental structure for several functions, both religious and political, which are to-day largely underestimated. We have tried here to render as completely as possible the remarkable diversity of functions assigned thereto. To conclude, we should hope to have given the reader a more precise and accurate idea of what the jubé actually was.

NOTES:

[1] Ed. note: Incidentally, the same intention resulted in a permission for German dioceses to replace the Latin propers with German chorales, presumably because Rome was afraid of the popularity of Luther’s Deutsche Messe, and in Pius IV’s permission for communion under both species for the dioceses of Mainz and Cologne, another concession to the Protestants. Gregory XIII rescinded this permission because most of the faithful in those dioceses actually refused to receive from the chalice.

Do we know what they were called in Iberia?

Also, this made we wonder whence developed the choir loft.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The screen in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela was called the “leedoiro”, from from the Latin “lectorium”, but the more general term for them (at least in Spanish) is “trascoro”, which is a bit of a misnomer since they mark the entrance to the choir rather than something behind or after it.

The choir loft was really a functional innovation of the post-Tridentine church layout which, having discarded the jubé and choir (or hidden it away behind the altar), needed somewhere to put the singers. As Donnay mentions in this article, some jubés survived the post-Tridentine “jubéoclasm” by being made into choir lofts (which Donnay calls “tribunes d’orgue”).

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Ambonoclasm”!

LikeLike

I found out today that in Portuguese it is called “coro alto”, which can also refer to the choir loft. Also, an acquaintance sent me a study on the “inexistence” of rood screens in Portuguese cathedrals, compared with European counterparts. I look forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If anyone would like to read the study, I can post the link here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please do!

I’ve seen it alleged that true rood screens were very rare in Spain, and that therefore Spanish churches anticipated the post-Tridentine focus on “the act of visual engagement and physical proximity to the ceremony of the Mass” (Religion, Space, and the Atlantic World, ed. John Corrigan). I’m skeptical, but it’s interesting that the same seems to be claimed about Portugal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can find it here:

LikeLike

Oops; pressed enter too quickly! Here is the link:

Click to access Li%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20para%20Provas%20de%20Agrega%C3%A7%C3%A3o.pdf

From what I’ve read so far, the two choir system in Portugal developed from monastic influence (though it odesn’t exactly explain that bit in detail). The “coro alto” was used by the cathedral chapter only, it seems, while the choir in the sanctuary was for solemn occasions with the bishop. Also, our cathedrals are very small compared to most of the European ones I’ve seen (which might also explain the absence of jubes).

LikeLiked by 1 person