Although in the popular mind to-day the Crusades are mainly conceived as the Christian effort to wrest the Holy Land from the Mohammedan grasp, they were in fact a wide-ranging military enterprise carried out in divers theatres to humble all enemies of Holy Church. The expeditions to the Holy Land proved ultimately to be a noble lost cause, but all was hardly quiet in the western front: the Crusades in holy Spain were an admirable triumph, banishing the spectre of the paynim from the Iberian peninsula for aye—or at least till the advent of modernity.

Taking advantage of the inner turmoil that afflicted the Visigothic kingdom, the Umayyad horde swept into Spain in the 8th century with astonishing celerity. A few Visigothic Christians were able take refuge in the mountains of Cantabria, however, and under the leadership of Don Pelayo struck a memorable victory against the invaders in 722, and began the arduous process of reconquering the peninsula.

The collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate allowed the Reconquista to enjoy great progress: the old Visigothic capital of Toledo was liberated in 1085 by Alphonse VI, king of Castile and Leon (and the figure principally responsible for imposing the Roman rite on Spain). Alarmed by the Christians’ victories, the petty Muslim chieftains of Iberia called for the aid of the brutal Almoravids, who held a north African kingdom centred on Marrakech. They won an alarming victory over the Christians at Sagrajas in 1086, after which they paraded the heads of the Christian dead around Spain and North Africa. This defeat led several Frankish knights to cross over the Pyrenees to succour their Spanish brethren, and although the Almoravid advance was halted, it was not reversed. Many of these knights would go on to participate in the First Crusade, and indeed the Spanish situation was very probably on the mind of the Blessed Urban II when he delivered that momentous sermon in Clermont, urging Christendom to resist the Muslim infidel.

Although this First Crusade was focused on bringing relief to the Byzantines and recovering the Holy Land, Pope Urban was keenly aware that the Spanish Reconquista was but another front of the same war, and when he learned that a band of Catalan knights was preparing to set off to the Holy Land, he urged to fight the Mohammedans in their own land instead. He specifically directed them to liberate the city of Tarragona, near Barcelona, promising them the same indulgences wherewith he had enriched the military pilgrimage to free Jerusalem, warning that “it is no virtue to rescue Christians from the Saracens in one place, only to expose them to the tyranny and oppression of the Saracens in another”.

Successive popes continued to encourage expeditions to free parts of Spain, and, in 1123, when Pope Calixtus II proclaimed the Second Crusade during the First Lateran Council, he specifically declared that knights could fulfil their Crusader vows in Spain as well as in the Holy Land. At a council held in Santiago de Compostela, Archbishop Diego Gelmírez declared,

Just as the knights of Christ and the faithful sons of Holy Church opened the way to Jerusalem with much labour and spilling of blood, so we should become knights of Christ and, after defeating his wicked enemies the Muslims, open the way to the Sepulchre of the Lord through Spain, which is shorter and much less laborious.

The Reconquista was not merely a political or military excercise, but an integral element of Spanish religious life. In a letter to King Ferdinand the Catholic, Diego de Valera captures this significance when he declares that “the Queen fights [the Muslims] no less with her many alms and devout prayers than you, my Lord, armed with the lance”. As such, it should not be surprising that certain decisive military victories became fixed in the liturgical kalendars of the various dioceses of Iberia.

The first victory to be commemorated liturgically was the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. As the chronicle of Don Rodrigo, Archbishop of Toledo—which was the source of the the Second Nocturn lessons in Mattins of the feast—relates:

Alphonse, king of Castille, called the Good, yearned to repair the losses inflicted upon the Christians by the Moors, who held Andalusia and the entire expanse of southern Spain and had once defeated him. He therefore raised a great host, called upon neighbouring kings and princes, and besought the Supreme Pontiff Innocent III to grant that those who should fall in this holy war might not be restrained by any capital offenses from soaring up to heaven forthwith 1.

Alphonse’s armies won a decisive victory on 16 July 1212, and thenceforth the Christians would permanently hold the upper hand in the effort to free the Iberian peninsula.

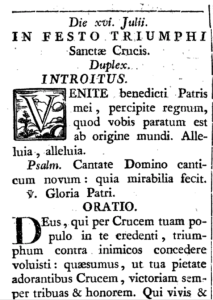

This victory was commemorated by the feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross in Las Navas de Tolosa (in festo Triumphi Sanctae Crucis apud Navas Tolosae). The name might have been inspired by the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which commemorated Emperor Heraclius’s defeat of the Persians, but the Mattins readings also recall miracles that occured during the battle:

And miracles occurred in this battle. First the paucity of Christian fatalities. A Cross, moreover, was seen in the sky by Alphonse and many others in the midst of the confrontation, when our side seemed most imperilled. Further, the Cross which was by custom carried before the Archbishop of Toledo, was twice carried into the enemy array, with the crucifer, Domingo Pascual, a canon of the church of Toledo, coming to no harm. And finally, a great multitude of Moors was crushed in the presence of an image of Our Lady, which was depicted on the royal standards. Wherefore, and because the Cross was the Christian ensign and emblem, this splendid victory was dubbed the Triumph of the Holy Cross 2.

This feast was a holy day of obligation in many Spanish dioceses during the Middle Ages, and it was one of the select feasts celebrated with a High Mass, Vespers, and sermon in the Royal Chapel of Castile. Some early liturgical books indicate that the propers of the feast were the same as those of the Exaltation except for the lessons at Mattins and the collect:

Collect: God, who by thy Cross willed to grant to the people who believe in thee victory against thine enemies: grant, that by thy mercy thou mightest ever secure victory and honour to those who adore thy Cross. Who livest and reignest, &c. (Deus, qui per crucem tuam populo in te credenti triumphum contra inimicos concedere voluisti: quæsumus, ut tua pietate adorantibus crucem: victoriam semper tribuas et honorem. Qui vivis et regnas, &c.)

Secret (borrowed from the feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross): Mercifully regard, O Lord, the sacrifice which we offer unto thee: that it might set us free from all the miseries of war; and by the banner of the holy Cross of thy Son, may establish us in the security of thy protection, so that we might overcome all the wiles of the enemy. Through the same Lord, &c. (Sacrificium, Domine, quod tibi immolamus, placatus intende: ut ab omni nos eruat bellorum nequitia; et per vexillum sanctæ Crucis Filii tui, ad conterendas adversariorum insidias, nos in tuæ protectionis securitate constituat. Per eundem Dominum, &c.)

Postcommunion (borrowed from a prayer said at the beginning of Mass in the Mozarabic rite): Hear us, O God, our Salvation, and by the triumph of the holy Cross, defend us from all dangers. Through our Lord, &c. (Exaudi nos Deus salutaris noster: et per triumphum sanctæ Crucis, a cunctis nos defende periculis. Per Dominum, &c.)

Later books, however, contain a proper Mass and Office, albeit compiled from preëxisting propers. Notably, they tended to come from Paschal masses, like the propers of the feast of the Liberation of Jerusalem.

Introit: Venite benedicti Patris mei, percipite regnum, quod vobis paratum est ab origine mundi, alleluia, alleluia. Ps. Cantate Dominum canticum novum: cantate Domino omnis terra. (From Easter Wednesday.)

Gradual: Haec dies quam fecit Dominus: exultemus et lætemur in ea. ℣. Dextera Domine fecit virtutem: dextera Domini exaltavit me. (From Easter Wednesday.)

Alleluia: Alleluia, alleluia. ℣. O quam gloriosum est regnum, in quo cum Christo gaudent omnes sancti; amicti stolis albis, sequuntur Agnum quocumque ierit. Alleluia. (From All Saints’ Day in certain uses.)

Offertory: Dextera Domine fecit virtutem: dextera Domini exaltavit me: dextera Domini fecit virtutem: non moriar, sed vivam, et narrabo opera Domini. (From the Second Sunday of Advent.)

Communion: Benedicimus Deum cæli et coram omnibus viventibus confitebimur ei: quia fecit nobiscum misericordiam suam. (From Trinity Sunday.)

There is some variation in the various mediæval versions of this feast, but as fixed in the post-Tridentine books, the Epistle pericope is the conclusion of St Paul’s letter to the Galatians (6, 14-18), where the Apostle exclaims, “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ; by whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world!”

The Gospel extract—Our Lord’s prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem and the end of the world (Luke 21, 9-19)—might seem odd at first: it appears to be a vision of apocalyptic terror rather than of triumph. Yet it reveals that the Spanish crusaders, like their counterparts in the Holy Land, saw their victories anagogically: despite the horrors of war or the end-times, the Christians will emerge victorious—capillus de capite vestro non peribit—and inherit not merely the kingdom of Spain, but the kingdom of heaven it represents. In fact, the introit is taken from the equivalent account of the apocalypse in the Gospel according to St Matthew: after much tribulation, the sheep shall be separated from the goats, and the everlasting king shall cry, “Come, ye blessed of my Father, possess you the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.”

The liturgical books of Seville included a sequence for this feast:

| Let Spain recall The new joys of the cross With happy jubilation. Remember the new grace, And the new victory, Under the patronage of the Cross. He wished to renew And the incredulous peoples The enemy of the Cross, Goes forth against Christ, In his pride he presses against the stars, While he ponders haughtily, For our patron, When he sees Behold, the lovers of the Cross Stirred by Christ the king, For such a victory, |

Nova crucis gaudia Recolat Hispania Laeto cum tripudio Novae memor gratiae Novaeque victoriae Crucis patrocinio. Cuncta qui disposuit, Et qui crucem sperneret, Crucis hostis impius Contra Christum nititur Fasta premit sidera Dum superbe cogitat Nam patronus, Cum necesse Ecce, crucis amatores, Excitati Christo duce Pro tali victoria |

The synod of Toledo held in 1536 under Cardinal Juan Pardo de Tavera confirmed this feast’s status as a day of obligation. After the Tridentine reforms, all the Spanish dioceses conformed their liturgical books to the Roman ones, but, at the request of King Philip II, on 30 December 1573 Pope Gregory XIII issued the bull Pastoralis officii permitting the lands subject to the Spanish crown to retain several local traditional feasts, including that of the Triumph of the Holy Cross; during this time the feast is also found in liturgical books from Portugal and the New World. In the course of the centuries, however, it was overshadowed by the increasing popularity of the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, also on 16 July, which was fixed onto the universal kalendar in 1726, although the Triumph continued to be celebrated in some dioceses of Spain until the liturgical reforms wrought in the aftermath of Vatican II.

The events of the Reconquista, then, like the rest of the Crusades, were of such religious import as to be worthy of being incorporated into the liturgical life of the dioceses of Spain, and thereby take their proper place in the history of salvation, themselves harbingers of greater victories to come.

Notes

1. Alfonsus Castellæ Rex, cognomento Bonus, cupiens damna Christianis a Mauris (Bæticam, totamque illam Australem Hispaniæ plagam possidentibus) illata resarcire (semel enim ab eis fuerat superatus) magnum conflavit exercitum: reges finitimos ac Dynastas solicitavit; condonationes a Summo Pontifice Innocentio Tertio impetravit, ut in eo pio bello qui caderent, nullis capitalibus commissis præpedirentur, quo minus ad cælos statim evolarent.

2. Miraque in hoc prælio contigerunt. Numerus primum occisorum in tanta paucitate Christianorum. Crux item in medio conflictu, cum nostri maxime laborare viderentur, Alfonso, quam plurimisque aliis visa est in aëre. Præterea Crux, quæ præsulem ante Toletanum de more gestabatur, bis (incolumi signifero Dominico Paschasio Toletanæ Ecclesiæ Canonico) aciem hostium sublata penetravit. Denique ad præsentiam imaginis beatæ virginis Mariæ, quæ in vexilla regiis depicta erat, ingens Maurorum multitudo corruit. Quare, et quod Christianis symbolum ac insigne Crux erat, Triumphus sanctæ Crucis hæc præclara victoria appellata est.

The Crusades even one of them led to the defeat (by Muslims) of the Byzantine Empire. That was not good).

LikeLike